Getting arrested is no laughing matter. For the common man, one’s knowledge of criminal proceedings is often confined to what is portrayed on television. With easy access to American television programmes, Singaporeans may be familiar with the Miranda warning – “You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say may be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided for you...” But how applicable is this locally when it comes to other similar US practices?

The glamorisation of criminal proceedings stemming from such American dramas have led to several misconceptions amongst the public. It seems apparent that many Singaporeans take comfort in the false sense of security that an encounter with the law is unlikely. Even if they do, there is always the potential hubris in believing that they already know what to do. Unfortunately, being unaware of one’s legal rights has led to dire consequences. In January 2016, a 14-year old boy was found dead at the foot of his block after being investigated for outraging the modesty of an 11-year-old girl. He was taken into police custody and released on bail on the same day of his death.

Following this incident, several questions were raised about how police investigations are conducted with youth suspects. In this article, we hope to address some of these issues and raise awareness of what one’s legal rights are, both to the youth and general public.

When may one get arrested and what happens during an arrest?

Arrestable vs non-arrestable offences

Perhaps the most important question therein is when may you even be arrested in the first place? In general, criminal offences are classified as either ‘arrestable’ or ‘non-arrestable’. Arrestable offences empower policemen to make an immediate arrest without a warrant. Conversely, for ‘non-arrestable’ offences, policemen must obtain a warrant for arrest to take the accused into custody. To find out whether an offence under the Penal Code is arrestable or non-arrestable, one has to look at the First Schedule of the Criminal Procedure Code (CPC). Common ‘arrestable’ offences include unlawful assembly, reckless driving, murder, sexual assault, voyeurism and cheating. In addition, offences found in other legislation such as the Misuse of Drugs Act or COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) Act can be found by referring to the particular legislation.

Bailable and non-bailable offences

Apart from the aforementioned classification, offences are also classified as ‘bailable’ or ‘non-bailable’. When an offence is bailable (e.g. cheating), the accused may be entitled to release on bail or personal bond. On the other hand, where the offence committed is non-bailable (e.g. rape), the Court has the discretion whether to release the accused. If bail is not granted, the accused will be placed in remand in prison. Whether an offence is bailable or non-bailable can be seen in the same table above under the fifth column. For the avoidance of doubt, the accused should seek advice from his/her lawyer.

Citizen’s arrest

It is also interesting to note that policemen are not the only people who can make arrests. Ordinary citizens may also make arrests if they witness the commission of an arrestable and non-bailable offence under section 66 of the CPC. These offences are typically grave offences such as kidnapping, rape, murder, robbery and theft. If a private arrest is made, the person making the arrest must turn the arrested individual over to the police as soon as possible.

Use of force

One would probably recall that in May last year, social media was bombarded with huge controversy over the death of an African-American male, George Floyd, during his arrest. How real, then, is this threat in Singapore? Should we be worried that such a tragedy may happen locally?

In Singapore, the arrest procedures are generally governed by section 75 of the CPC. In making an arrest, the police officer must touch or confine the body of the person to be arrested unless he submits to arrest. If the person resists, the police officer may use all reasonable means necessary to make the arrest. Furthermore, the person arrested must not be restrained more than is necessary to prevent his escape under section 76. Thus, to avoid unnecessary use of force, the accused will likely benefit from complying with the arrest and the instructions of the police. Though section 63 of the CPC empowers police officers to act in any manner (including anything that is likely to cause death), this is only under specific circumstances where the officer has reasonable grounds to believe that the person is about to do something which may amount to a terrorist act; and that such act by the police officer is necessary to apprehend the person.

Can police officers search my home?

Search for persons

A police officer may search one’s place of residence if they have reason to believe that the person to be arrested is inside the place. The owner of the residence is obliged to allow the police officers free entry and provide all reasonable facilities for a search. Moreover, every person found in the residence may be lawfully detained until the search is complete. It is important to note that the police officer must state his authority and purpose for demanding entry. For women, searches must be conducted by a female personnel unless the police officer has reason to believe that there is terrorist conspiracy involved or that time is of the essence.

Search for objects

In general, personnel can only conduct such searches if the Court grants a search warrant. The search warrant should be in writing and will bear the seal of the Court, valid only for the number of days stated. The “searcher” must identify himself to the occupier, show evidence of his identity (e.g. police ID), show the occupier the warrant, and if the occupier requests, he/she must also provide a copy of the warrant to the occupier. However, a warrant may not be needed if the personnel has reason to believe (a) that there is a person unlawfully confined in the place and a delay would adversely affect the rescue of this confined person, (b) that there is stolen property concealed in the premises and delays would likely lead to the removal of such items, (c) that there is crucial evidence concealed which would likely be removed.

Seizure of items

Police officers may also seize or prohibit the disposal of or dealing in any property which is suspected to have been used or intended to be used to commit an offence; or which is suspected to constitute evidence of an offence. One should note that the police officer must prepare and sign a list of all things seized during the search, recording the location where each such thing is found. The occupier may attend the search and must be given a signed copy of the list. In cases involving computers, police officers may also access, inspect and check the operation of a computer which he/she has reasonable cause to suspect that it was used for the commission of the offence or contains crucial evidence. They may search any data contained in the computer and make copies of such data and may prevent any other person from gaining access to the computer.

What happens upon arrest?

Upon arrest, the accused may be detained for up to 48 hours while investigations take place. During this time, the police officers will interrogate the accused and search for more facts about the case. The police officer may also search the places as aforementioned. What is one entitled to during this time?

What rights are you legally entitled to during investigation proceedings?

At this juncture, it is imperative to stress once again that investigation proceedings in Singapore differ greatly from what is portrayed on television. It is essential that one knows their actual legal rights when being detained by the police. Moreover, even if one is not being arrested, he/she may be called to help with the investigation proceedings.

The right to remain silent

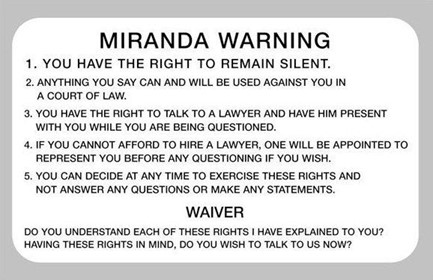

Now to deal with the infamous question, do you really have the right to remain silent? As mentioned earlier, most people would have heard of the Miranda warning, arising out of the Fifth Amendment in the US Constitution which protects one’s rights against self-incrimination.

An example of the Miranda Warning

In Singapore, the situation is more complex. There is a statutory privilege against self-incrimination. Section 22(2) of the CPC, states that “the person examined shall be bound to state truly what he knows of the facts and circumstances of the case, except that he need not say anything that might expose him to a criminal charge, penalty or forfeiture”. However, other statutory provisions give the police a great deal of investigative powers. In practice, this means that while you are technically allowed to remain silent, this might be counted against you. Section 23 of the CPC essentially states that the withholding of information (even if you reveal it later) might cause the judge to be less likely to believe you. Furthermore, it is difficult to know exactly what facts may be helpful in defending your case, and you may hence either (a) say something that incriminates you or (b) keep silent about something that may help you in court.

Unlike the US, where police officers are required to issue the Miranda warning, the Singaporean police are not bound to inform you of your right to remain silent, and in most cases, therefore, they don’t. This lack of warning does not affect the admissibility of your statement (ie. what you say can still be used in trial). Having a lawyer present would help greatly, but in most cases, as we will further discuss below, you would only get access to one after being interrogated. Human rights lawyers such as M Ravi have argued for a restoration of the right to remain silent during police interrogations, as it is a “constitutional right” which becomes particularly important if you are “convicted on your confession alone”.

The right to amend or delete parts of your statement

While being interrogated, police officers will record your statements and return them back to you for signing. These statements will be recorded in English and a translator will be available, upon request, should you be unable to speak or read English. Upon signing the statement, one is then unable to subsequently amend it. You should note that nobody can force or coerce you into signing your statement. You can amend or delete parts of your statement until you are fully satisfied, before signing it. This is particularly important in situations where there is a third-party transcribing the information, as they might unintentionally change the meaning of words.

The right to counsel

The Singapore Constitution guarantees citizens access to a legal practitioner of his/her choice under Art 9(3). However, another stark difference from television shows is the timing which one can get access to an attorney. In most shows, the accused gets access to a lawyer immediately upon being arrested, or “lawyering up”, and the lawyer would be present during investigation proceedings. However, in Singapore, this is not the case. It was established in the case of Jasbir Singh v Public Prosecutor that an arrested person is only to be granted access within a “reasonable time from his arrest”. The definition of a “reasonable time” includes time required by the police to conduct the investigation, including transportation of articles or people. In essence, this means that you may not be granted immediate access to a lawyer upon being convicted. In James Raj v Public Prosecutor, the court affirmed that the right to counsel under Art 9(3) of the Singapore Constitution cannot be exercised immediately after arrest. The court pointed out that such a right only had to be exercised “within a reasonable time” after arrest so that police investigations are not hindered.

It is hence essential that you know your legal rights, most importantly the right to remain silent, as you will likely not have the help of a legal counsel. It is proposed that the right to counsel under Art 9(3) of the Singapore Constitution should be given its full effect rather than allowing the police to trump the Constitution by deciding on what a reasonable time after arrest is. Furthermore, what do lawyers present in an investigation do that would hinder a lawful investigation? If a lawyer’s primary duty is to the Court, then it is in the best interests of all stakeholders including the police that an investigation is carried out lawfully.

The right to a phone call when being investigated

Upon being arrested, it is normal to feel anxious, particularly if you are under the age of 21. You have the right to request to make a phone call to your family members. However, should the phone call possibly interfere with police investigations, you may be denied your request. Nonetheless, you should ask for these requests to be recorded (including that they were possibly denied), as this may be beneficial in later proceedings.

Other rights

While being investigated, you may also request for food, drinks or toilet breaks. Furthermore, if you feel unwell, you may request for permission to see a doctor. All such requests should also be recorded.

Right to have a legal guardian present (if you are under the age of 16)

Following the suicide of Benjamin Lim, the Appropriate Adult (AA) Scheme was introduced by the Ministry of Home Affairs. Under this scheme, youth suspects will be accompanied by trained volunteers during the interrogation process. The volunteer will not give legal advice, but will rather ensure that the accused understands the questions posed to him/her, and that the investigations officer understands the accused’s answers. While more can be done to ensure the proper handling of young suspects, the presence of a third party serves to alleviate parents’ concerns, as well as provide comfort to the youth.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is evident that much of what we see on television is starkly different from the actual situation in Singapore. We hope that this article has clarified some doubts and provided essential information on how to be prepared for the unforeseen. For more information, one may wish to look at the various government websites (such as the Ministry of Law, Ministry of Home Affairs, etc.), the various legislation found online (notably the Criminal Procedural Code and the Penal Code) and the Law Society of Singapore’s website.

Mavis Ng and Ryan Leong

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.