CJC-F Announcements, CJC-F News, Uncategorized

A Glimpse into the Abyss: Forensic Psychology and the Criminal Minds

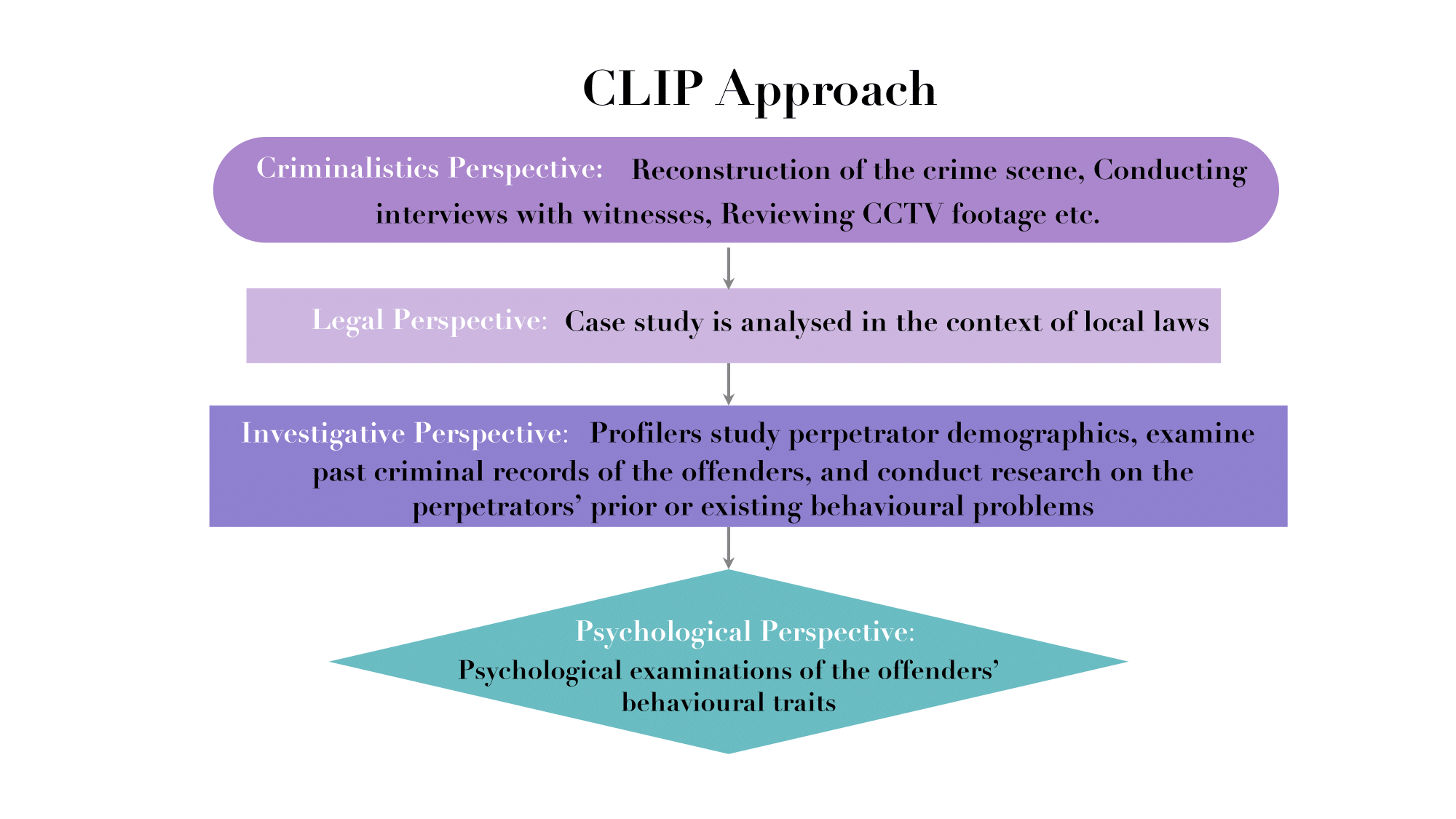

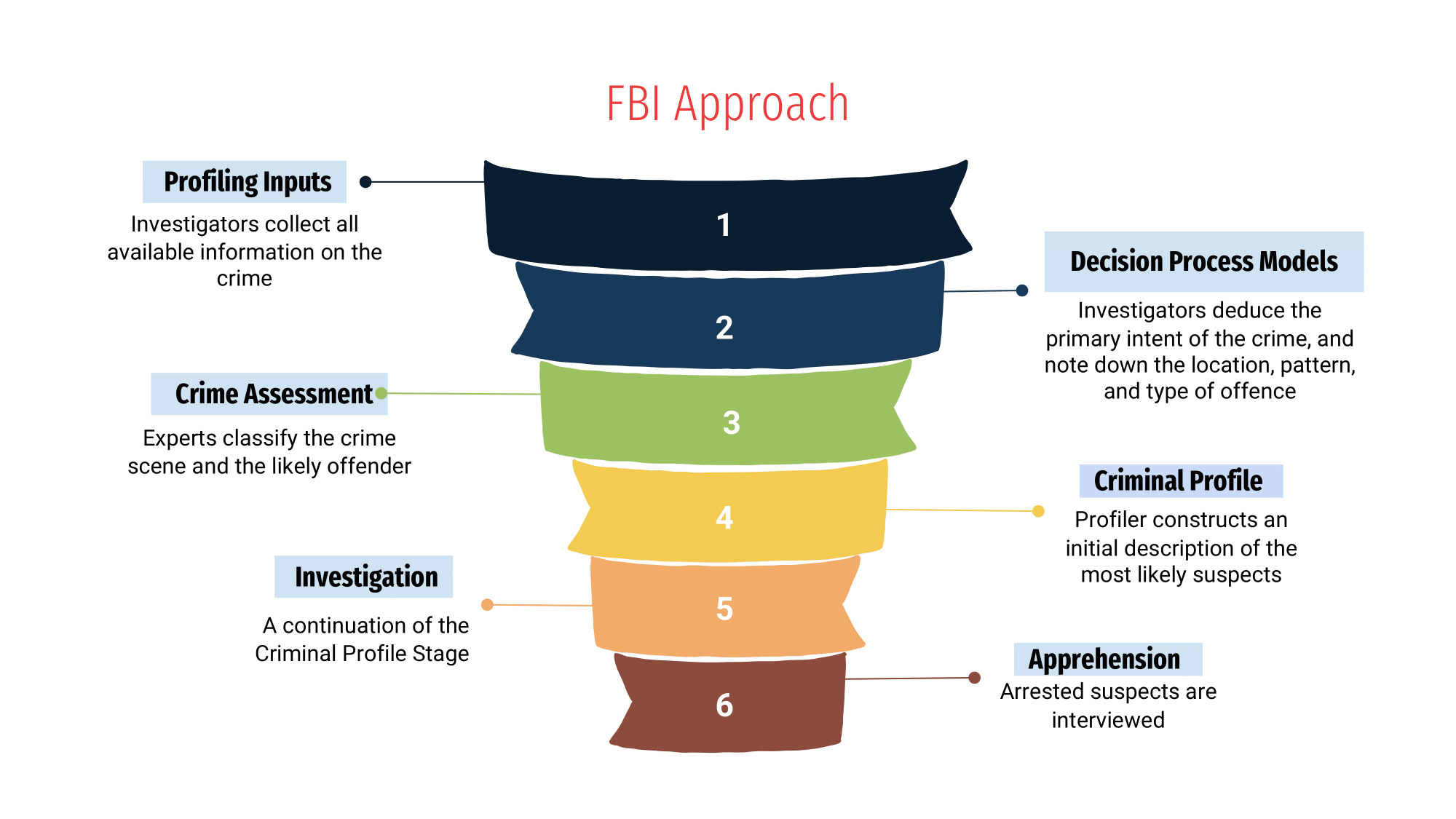

According to the American Board of Forensic Psychology (ABFP), forensic psychology is the application of the science and profession of psychology to questions and issues relating to law and the legal system. Conceptually, forensic psychology is both a field of application and research. As such, this subject rivet the interest of many including both practitioners and academics alike. Forensic psychology is a broad term that encompasses all forms of research and application in psychology to law and the legal system. There are four main sub-fields within forensic psychology that specifically cater to different sections of the spectrum in the legal system, namely i) forensic-law enforcement psychology (FLEP), ii) forensic-clinical psychology (FCP), iii) forensic psychology in academia, and iv) forensic-legal psychology. Forensic-law enforcement psychology is defined as the research and application of psychological principles and clinical skills to law enforcement and public safety. In Singapore, FLEP-oriented psychologists are engaged by the police, immigration, security departments, and the Home Team Behavioural Sciences Centre. The nature of their work primarily revolves around three main areas: i) applying psychological knowledge to strengthen law enforcement organisations (e.g., personnel selection, leadership assessment and development), enhancing law enforcement operations (e.g., criminal profiling, negotiations, crisis response, detection of deception, morale assessment, victim support), and lastly iii) providing services for law enforcement staff (e.g., counselling programs). Forensic-clinical psychology emphasizes on forensic mental health and is basically the application of clinical expertise in forensic settings. In Singapore, FCP-oriented psychologists work in the psychology departments at Singapore Prison Service (SPS), Central Narcotics Bureau of Singapore (CNB), the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF), Courts psychology branch (CAPS), and the Institute of Mental Health (IMH). The nature of their work is clinically oriented, with an emphasis on risk assessment, intervention, rehabilitation, and therapy and treatment of offenders, as well as providing psychological aid to victims of crime or trauma. Forensic psychology in academia focuses on academic teaching and research. Although uncommon in Singapore, it is possible for forensic psychologists to work exclusively in the academic field and contribute in terms of the discovery and transfer of knowledge. In Singapore, there are limited forensic psychology modules and most academics teaching them in tertiary institutions are full-time practicing forensic psychologist in external organisations. Lastly, forensic-legal psychology (also known as legal and courtroom psychology) is the research and application of psychology to legal issues in both criminal and civil litigations. Psychology can be employed to assist in a myriad of legal issues in the courtroom such as accuracy of eyewitness testimonies, reliability of confessions, the effects of punishment, judge/jury decision-making, child custody determination, and reliability of victim or child testimony. This is another growing sub-field in Singapore and is expected to continue being so in the near future with the increasing assimilation of psychology into the legal system as courtrooms adopt a multidisciplinary approach in judicial discrimination. Criminal Profiling Due to popular TV series such as ‘Criminal Minds’ and ‘Mindhunter’, the idea of criminal profiling has drawn huge traction among ‘CSI’ enthusiasts. However, is criminal profiling what the popular media has portrayed? Can profilers deduce suspects by simply looking at the crime scene? Is criminal profiling all about apprehending offenders? The following sections aim to discuss these questions. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) defined criminal profiling as a technique for establishing the personality and behavioural characteristics of an offender based on an analysis of the crimes committed. Briefly, it involves observing the crime scene and deducing who the offender is. However, criminal profiling has evolved significantly over the years. Nowadays, profiling not only identifies the offender but also involves understanding the sophistication of crime. On the other hand, Khader defined criminal profiling as an investigative and operational support technique, where information is analysed using a multidisciplinary approach to infer the behavioural and mental characteristics of offenders and the ‘behavioural correlates’ involved in a crime type with the purpose of providing recommendations for crime prevention, detection, investigation, and rehabilitation. This second definition provides a comprehensive summary of criminal profiling and it highlights five distinctions: Applications of Profiling Profiling has other uses in practice, apart from conventional identification of offenders. First, criminal profiling may be used to understand the behavioural correlates of crime types and help build up a scientific knowledge base of the study of criminal behaviour. Second, profiling may be useful in enhancing the effectiveness of crime-prevention efforts. For example, most perpetrators of child abuse are usually not strangers but people who the victims know. With this information, the police are able to tailor crime-prevention programs accordingly and remind children to be aware of inappropriate sexual behaviours even from their own family members. Third, profiling criminals may provide insight into the narratives that criminals frequently adopt, equip interviewers with ideas to develop interviewing strategies, enable rapport building, and provide insights into different types of potential deception. Fourth, a profile of a person may be used successfully in a courtroom trial strategy. Fifth, profiles may be useful for the design of rehabilitation programs. For instance, a profiling program, which studies the cognitive distortion patterns of sex offenders, will be useful in the designing of a rehabilitation program that aims to reframe these patterns of distortion. Lastly, profiles may also be useful for policymaking. For example, knowing the profiles of those who take loans from loan sharks may allow policymakers to work with banks to design micro-loans schemes, which are more affordable and less damaging to borrowers. Main approaches in criminal profiling CLIP Approach There are several approaches towards criminal profiling. In Singapore, the CLIP methodology is employed in the analysis of crimes and criminal behaviour. Drawing upon knowledge from multiple disciplines, the CLIP methodology provides a focused and broad, multi-perspective approach to criminal profiling. To obtain a clearer understanding of this criminal profiling methodology, CLIP will be broken down into its four constituent perspectives, encapsulated in its acronym. The first perspective examines “C” or the “Criminalistics and Forensic Sciences Considerations” associated with a crime – helping criminal profilers to decipher and ascertain how a crime occurred. The second perspective then examines “L” or “Legal and Local Considerations” of the crime, which involves analysing the legal elements of the crime in the context of local jurisdiction. Next, the third perspective considers “I” or the “Investigation and Law Enforcement Considerations” of the case, which places emphasis on the process of interviewing and investigation. Essentially, this perspective focuses on optimising such procedures, such that the scope of suspects can be narrowed down more efficiently, and to expedite the process of solving the crime. Finally, the fourth perspective is concerned with “P” or the “Psychological and Behavioural Considerations” of the crime, which entails a close examination of the criminals’ psychological traits for experts to glean an in-depth understanding of the nature of the crime. Thus, to maintain a cohesive approach to various crimes of interests, criminal profilers employ all four perspectives under the CLIP framework in their analyses of crimes. One instance in which the CLIP framework has been applied to real crimes, is the analysis of a series of five case studies, revolving around a phenomenon known as “happy slapping”. The term “happy slapping”, which attained public notoriety in 2005, generally refers to an act where victims are publicly humiliated and physically assaulted in various manner that can range from kicking and hitting to sexual assault. After the entire process has been recorded, the videos are then uploaded to the Internet and circulated on various social media platforms. Hence, to document a deeper understanding of this phenomenon, a team of Singaporean researchers produced a research paper detailing the analysis of the aforementioned crimes using the CLIP framework. Starting off with the “Criminalistics” perspective, the researchers first proposed reconstructing the primary crime scene – where the victims were assaulted, followed by the secondary crime scene – where recordings of the assaults were distributed. This entailed collating evidence from the physical examinations of both the victims and the primary crime scene, as well as conducting interviews with witnesses, and reviewing CCTV footages. Additionally, in recognising the digital nature of the crime, the researchers also recommended focusing on digital forensics – to extract, examine, and compile digital evidence from electronic devices to be analysed alongside physical evidence collected. Under the “Legal” perspective, the researchers then proposed for each case study to be analysed in the context of local laws and for punishment to be meted out accordingly. This was necessary for the CLIP framework to take into account how local laws varied indefinitely from international laws since each case study took place in a different country. Moving on to the “Investigative” perspective, the researchers recommended several measures to improve the efficacy of investigations. For instance, they suggested that profilers study perpetrator demographics, examine the past criminal records of the offenders, and review prior or existing behavioural problems in areas of the perpetrators’ lives to better understand the complex nature of “happy slapping”. Furthermore, to bolster the quality of information obtained from interviews, the researchers stressed the need for interviewers to engage in building rapport with the interviewees, which they believed would help create a comfortable and low-stress environment to facilitate cooperation, and allow for optimal, relevant, and accurate information to be obtained. Finally, researchers felt that aspects pertaining to the “Psychological” perspective could include deciphering the motivations behind the perpetrators’ actions, psychological examinations of the offenders’ behavioural traits, and also gaining a deeper understanding of victim psychology. Conclusively, they felt that the aforementioned measures were pertinent, as a more in-depth glimpse into the psychological states of the offenders and the victims could assist rehabilitation and recovery process for each group respectively. Overall a unique methodology employed in Singapore, the CLIP framework is advantageous that it is multidisciplinary, and thus enables a more well-rounded analysis of crimes through marrying knowledge from a diversity of fields including Forensic Science, Law, and Psychology. Furthermore, the CLIP methodology is particularly useful for examination of a crime within a local context. FBI Approach Another prominent methodology would be the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) approach. The FBI methodology utilises a six-step comprehensive process to construct the perpetrator’s criminal profile. During the first stage – “Profiling Inputs”, investigators collect all available information on the crime, including forensic evidence, the victim’s background, and the nature of the crime scene. At the second stage – “Decision Process Models”, investigators then try to deduce the primary intent of the crime, and further note the location, pattern, and type of the offence. In the third stage of profiling – “Crime Assessment”, arguably the most crucial stage of the analysis, experts classify the crime scene and the likely offender. According to the police investigators, crime scenes are either “organised” – neat and tidy with little to no traces of evidence, or “disorganised” – messy sites that often contain evidence left behind by the offender. Once investigators have discerned the nature of the crime scene, they then categorised suspects into either “organised” or “disorganised”, in an attempt to predict the demographic and behavioural characteristics of the offender. For instance, based on his or her modus operandi, a criminal offender who has been labelled as “organised” is predicted to lead an orderly and structured life. In general, he or she is also thought to be socially competent, of higher-than-average intelligence, and is likely to have stable employment. Conversely, a “disorganised” offender is seen to be disordered, dysfunctional, and generally less socially competent and intelligent than an “organised” offender. This is further evident from the nature of their crime scenes – a “disorganised” offender is more likely to leave behind incriminating evidence such as fingerprints, semen, blood, or even the murder weapon, unlike an “organised” offender. Finally, in the fourth stage – “Criminal profile”, the profiler constructs an initial description of the most likely suspects, which will be further focused on in the fifth stage – the “Investigation” phase. In the final stage – “Apprehension”, arrested suspects are interviewed, and the criminal profile is assessed to determine how well it matches the accused suspect. One of the most infamous applications of the FBI Approach to a real criminal case is the case of Ted Bundy, one of the most prolific serial killers in US history. Having confessed to the murders of over 30 girls, Bundy was regarded as a notorious, manipulative, and sadistic killer who was able to utilise his charisma and good looks to lure women in before brutally raping, assaulting, and killing them. Having performed a psychological assessment of Ted Bundy, the FBI was able to classify him as an “organised” offender, decipher his modus operandi, and gain insights into his crime pattern as well as the demographics of people most vulnerable to his attacks. For instance, in the first stage of the FBI approach, the police were able to identify a common characteristic amongst the victims – they were all young women between the ages of 12 and 23. Moving onto the second and third stages of the FBI Approach, the FBI profiled Bundy as a “control” serial killer, whose primary intent as a killer was to seek pleasure in dominating and torturing his victims. Noting how Bundy typically killed his victims slowly, the FBI deduced that Bundy exhibited such sadistic behaviour to empower himself and further seek pleasure in his domination of the young women. They thus classified him as an extremely cunning and unemotional character, who was likely to be charming, handsome, and of keen intellect. Having constructed a rough criminal profile of Bundy, the FBI began to find links between the different murders which occurred across 7 different states in America. For instance, upon conducting interviews with passers-by and witnesses in these various areas, increasing number of people began to identify Ted Bundy in pictures or through verbal descriptions, and his name rose higher up in the FBI’s suspect list. This led to his eventual arrest when Bundy was found to have matched the criminal profile constructed by the FBI, and later incriminated with forensic evidence (hair from the victims) found in his car that nailed him responsible for the series of murders. After the arrest of Ted Bundy, the FBI continued to play an increasingly pivotal role in applying the insights of forensic psychology to violent criminal behaviour, in a comprehensive way. However, while the FBI approach has been proven to be successful, there are also inherent flaws with this methodology. For instance, the “organised” and “disorganised” typology do not always allow for accurate predictions to be made about the offender. In fact, this framework has long since been heavily criticised by the scientific community, claiming that the FBI methodology lacks scientific methodological rigour, as it leads to an oversimplification of complex variables into dichotomous categories. Juxtaposed with the CLIP methodology, it appears that the CLIP approach – which draws on properly established research, is more scientifically accountable and accurate as opposed to the FBI approach. Furthermore, the FBI approach results in criminal profiles that are constructed purely within an American context, making it difficult to apply such profiles to non-American settings, especially Asian settings. Therefore, it has limited applicability in Singapore. Investigative Psychology Approach Another methodology adopted in criminal profiling would be the investigative psychology approach, devised by a British professor, David Canter. Basing his work off the interactions between criminal offenders and their victims, he stressed the need for psychologists to gather data and examine relationships between a large number of variables within a crime scene, in order for the detection of crime to be effective and legal proceedings to be appropriate. To better illustrate his theorem, Professor Canter has also constructed an investigative cycle giving rise to the field of investigative psychology. Starting off with “Investigative Information”, Canter proposes that at this stage, possible suspects and possible lines of enquiries should be identified, such that the search focus can be progressively narrowed down. He also states that the compilation and assessment of evidence should be completed within this stage, such that experts can make decisions to move closer towards the arrest and conviction of the offender. Moving onto the stage of “Appropriate Inferences”, psychologists should be able to draw appropriate conclusions from the accounts available of the crime, and to predict models of how various offenders behave. With this line of thinking, the criminal experts can then move towards arresting and convicting suspects in the “Action” or “Apprehension” stage. Professor Canter’s official development of the investigative psychology approach took place after he had played a significant and crucial role in finding the perpetrators of a spate of serial rapes and murders in the United Kingdom. Known as the “Railway Rapists”, John Duffy and David Mulcahy had raped and killed several women and a child at railway stations in Southern England during the 1980s. Despite no prior application of “psychological offender profiling” at the time, Canter analysed details of the crimes and carefully constructed a profile of the perpetrator’s personality, characteristics, and habits, utilising the investigative psychology approach. With Professor Canter’s help, both offenders were eventually caught – and it was even discovered that Duffy matched 13 out of 17 observations Canter had predicted about his lifestyle. From then on, psychological profiling became commonplace in England, and Professor Canter decided to further develop this approach. While the investigative psychology approach is scientifically grounded and theoretically sound, police investigators have commented that, in reality, it is difficult to apply his methodology as frontline police officers find it complex and difficult to follow. This, in turn, leads to greater confusion and an overall slowdown in productivity. Furthermore, some have also pointed out how police investigators want criminal profiles which can help them solve the case as swiftly as possible, rather than a framework which compels them to overly consider theories on offender motivations, and perpetrators’ psychological assessments. Conversely, the CLIP methodology appears to be more straightforward in its implementation, whilst maintaining a high degree of accuracy and reliability as it involves drawing from multiple areas of research. Hence, this is another reason why the CLIP approach is favoured by Singapore. Clinical Approach Lastly, the field of clinical psychology has also been applied to profiling. The clinical approach leverages literature from clinical psychology, personality and psychopathology in an attempt to identify the offender’s motivation and to generate probable behavioural traits of the offender. This approach primarily relies on the clinician’s expertise and experience from working with individual clients, and the application of these clinical experiences to generate inferences and conclusions from crime scene information. One famous case in which the clinical approach was utilised in an investigation was the murder of Rachel Nickell in 1992. Nickell was a 23-year-old Briton who was attacked and beaten to death while out walking with her son. An unemployed man named Colin Stagg was identified to be the main suspect. However, given the lack of forensic evidence linking Stagg to the crime, the police turned to Dr Paul Britton, a clinical psychologist with experience in profiling, and came up with a profile of the killer. The police decided that Stagg fitted the profile, and Britton assisted the police in crafting a covert operation based on their knowledge of the killer. Britton believed that the killer was a sexual sadist, who enjoyed engaging in self-harm. In the sting, an undercover policewoman drew out Stagg’s violent and sexual fantasies through multiple interactions and conversations. Stagg was arrested on the basis of his conversations. However, during the trial, the judge ruled that the police demonstrated ‘excessive zeal’ in an attempt to entrap a suspect by means of deception. Dr Britton’s evidence was regarded inadmissible and the prosecution withdrew the case. This case highlights the importance of research and evidence-based advice in criminal profiling. Britton’s profiling advice was opinion based and he exaggerated the effectiveness of his methods. The clinical approach differs from the other approaches in that it often assumes maladjustment or mental illness as the main driving force of crime. While it may be true in some instances, such an assumption cannot be generalized to all cases. The CLIP approach has an advantage over the clinical approach as it is multidisciplinary in nature and considers other evidentiary in putting the case together. This allows it to account for instances where the offender is not truly mentally unsound or ill and can leverage on other relevant disciplines such as forensic science and law to support their analysis. Furthermore, the behavioural manifestation of maladjustment or mental illness often differs across cultures as well. Again, the CLIP approach is preferred in Singapore as it is more comprehensive compared to the clinical approach, taking into consideration the local culture, environment, and context in profiling. Special Section: Cyber Forensics and Applications to Profiling As technology becomes increasingly prevalent in connecting the physical and virtual world, it has also created new opportunities for criminal activity. Perpetrators make use of the internet to lure victims, gather information, fabricate alibis to protect or alter their identities. This is not limited to cybercrimes but violent crimes, such as homicide and sexual assault, where key forensic evidence is usually physical in nature, can also involve digital evidence either directly or incidentally. An individual’s online activities are more often than not, still recognizable and reflective of their behaviour in real life. These online activities give insights into the actions and thoughts of the offenders and victims, which can help create a behavioural archive of their motivations, interests and desires. Given its investigative usefulness and ubiquity, investigators should learn to identify relevant digital evidence and interpret it from a behavioural standpoint. For example, an offender’s web search history can reveal the kind of crime the offender intends to commit. Pornographic, violent, or racist content in the offender’s computer could elucidate the motivations and state of mind of the offender as well. Phrasing and content of sentences, unusual word usage or spelling errors in emails or online communications can also provide insight into an offender’s state of mind, motives, and any possible psychological disorders. The case of the ‘Wifi Spoofer’ highlights how cyber forensics and digital evidence can assist in establishing a profile of the offender, especially in the absence of physical evidence. In this particular case, an unnamed company and its clients were harassed by embarrassing emails containing derogatory and sexually explicit attachments. These emails were spoofed to appear that the senders were executives from the company. Behavioural analysis of the harassing communications revealed that the offender was a sole individual, based on his high ratio of ‘I-to-we.’ From the sexually explicit and demeaning content in the offender’s email, investigators believed that the offender had some form of serious psychological problem. The sophistication and persistence of his attacks demonstrated a high risk of violence towards the company. Based on the offender’s vocabulary and historical references in the email, profilers indicated that the subject was most likely a male over the age of 30. The use of high numbers of negatives, rhetorical questions and negative evaluators in the offender’s emails suggested a strong resentment towards the target company. Email communications were established with the offender, and with the help of a behavioural psychologist, the motivation of the perpetrator was elicited – to extort money from the company. Subsequent surveillance of the locations utilised by the perpetrator to send the spoofed emails led investigators to a prime suspect, who fitted many of the characteristics of the profile. In one of the earliest communications, investigators found that the offender had tracked information on ricin, a deadly toxin, indicating that the offender was possibly dangerous and mentally unstable. This prompted investigators to take caution when they were conducting his arrest. As predicted by the profile, when investigators from the FBI arrested him in his home, they found firearms, components for hand grenades, and the formula and tools for making the deadly ricin. The ‘Wifi Spoofer’ case illustrates how behavioural analysis of digital evidence provides critical information for profiling in investigations, such as the skill level of the offender, motivations and intent of the offender, and the physical security risk or threat the offender poses. It may be worth mentioning that while cyber forensics and digital evidence can provide important and additional insights to profilers regarding the offender, it is not an isolated approach to profiling. Rather, it is a tool that complements existing approaches, including those aforementioned. Currently, the application of cyber forensics in profiling is still in its infancy phase. However, with the rising threat of cybercrimes and tech-facilitated crimes, there is an increasing need for the assimilation of cyber forensics into profiling. Further research in this aspect will prove to be invaluable in the near future. Conclusion In conclusion, forensic psychology is a broad field that encompasses all research and application of psychology pertaining to law and the legal system. It spans across four main strands: i) forensic-law enforcement psychology, ii) forensic-clinical psychology, iii) forensic psychology in academia, and iv) forensic-legal psychology. The first two sub-fields are prominent in the local context. As for criminal profiling, it is unfortunately not as ‘sexy’ as what the popular media portrays it to be. Nevertheless, criminal profiling has wider uses beyond what it is typically known for – a mere investigative tool for deducing offenders. Although the utility of criminal profiling has drawn some doubts and criticisms from the scientific community, it is still employed by many law enforcement agencies today as it is a useful heuristic tool. Admittedly, while profiling may not always be successful, it does not warrant rejection as an important investigative instrument. Rather, it would benefit to capitalise on the potential while sidestepping the limitations of profiling when put to use. Furthermore, with the growing use of digital evidence for criminal investigations, cyber forensics adds a new dimension to profiling and adds an impetus for its utility in this technological era.

What is Forensic Psychology?

Definition

Diagram 1: Overview of the CLIP Approach

Diagram 2: Overview of The FBI Approach

Diagram 3: Investigative Cycle

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

Authors’ Biography

George Teo is a Year 3 FASS undergraduate and a member of the CJC-F “Forensic Psychology” project. He is pursuing a major in Psychology and a minor in Forensic Science. He has a strong interest in forensic psychology, specifically its applications to law enforcement and rehabilitative efforts.

Carolyn Chan is a Year 1 undergraduate from the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. As a member of the CJC-F “Forensic Psychology” project, Carolyn has helped to write articles and also create awareness sharing posts for social media. With a keen interest for sociology, Carolyn is interested in exploring the intersections between sociology, psychology, and law in crime investigations.

Tan Wei Liang is a Year 4 Psychology undergraduate, with a minor in Forensic Science. With a strong passion in forensic psychology, Wei Liang aims to pursue his postgraduate studies and subsequently a career in this field. As one of the project managers of CJC-F (Forensic Psychology Division), he spearheads the project’s programme planning and newsletter publication. Ultimately, he hopes to raise awareness about the field of forensic psychology and advocate for its application in the criminal justice system.

Zheng Yen Phua is a teaching assistant for the Forensic Science programmes at the Faculty of Science. He holds an honours degree in science from NUS and is currently a doctoral researcher. The modules which he is actively involved in teaching are: LSM1306 Forensic Science, SP3202 Evidence in Forensic Science, SP4261 Articulating Probability and Statistics in Court, SP4262 Forensic Human Identification, SP4263 Forensic Toxicology and Poisons, SP4264 Criminalistics: Evidence and Proof, SP4265 Criminalistics: Forgery Expose with Forensic Science, SP4266 Forensic Entomology and LL4362V/FSC4206 Advanced Criminal Litigation – Forensics On Trial. He also received Honourable Mention as Expert Witness for the NUS Forensic Science Expert Advocacy Cup 2020.

–