Recently, the exercise of prosecutorial discretion has come to the fore in certain high-profile criminal cases. In the 2017 Annie Ee case, where an intellectually disabled woman was extensively tortured to death by her flatmates, the prosecutorial decision to charge the couple with voluntarily causing grievous hurt as opposed to murder or culpable homicide sparked heated furore amongst the community. In 2019, while reviewing the High Court’s conviction of P. Mageswaran who was charged with culpable homicide instead of murder, the Court of Appeal opined that the Prosecutor had preferred this lesser charge “having weighed all the relevant circumstances in the exercise of prosecutorial discretion”.What is the nature of the Prosecutor’s discretionary powers, and what are the legal limits that circumscribe them (if any)? This article seeks to shed light on this widely misunderstood feature of our criminal justice system.

What is prosecutorial discretion?

In Singapore, the Public Prosecutor (PP) is the Attorney-General (AG). Article 35(8) of Singapore’s Constitution confers upon the AG an “unfettered” discretion over the initiation, conduct and discontinuation of criminal proceedings provided that it is exercised constitutionally and in good faith. However, the AG does not exercise this function alone, as he appoints Deputy Public Prosecutors (DPPs) and Assistant Public Prosecutors (APPs) to carry out the duties of the PP. Collectively, they are known as the “Prosecution”.

Essentially, Art 35(8) means that the Prosecution can decide whether, what, and how many charges to press against accused persons; and whether certain charges should be dropped or dismissed. The Prosecution can also bring and recommend divergent charges and sentences for two offenders who have committed substantially the same offence, or were involved in the same criminal enterprise.

What is the underlying rationale for prosecutorial discretion?

Prosecutorial discretion exists to safeguard the efficiency of criminal justice systems, as “automatic prosecutions” would only create a deluge of prosecutions and overwhelm the courts.

In some cases, the offence may be trivial in nature, such that conducting a prosecution may not be worth the judicial resources consumed. The Prosecution may also decide that the accused should be given a second chance – perhaps issuing a conditional warning is more warranted than bringing him to court. Thirdly, the charges that are brought must reflect the culpability of the accused person – sometimes, many charges can be levied against an individual, and the most appropriate one must be chosen. Therefore, the Prosecution’s decision-making ability is both necessary and justified. The indispensability of prosecutorial discretion also illuminates why it is an essential element of many criminal justice systems and can be found in other common law jurisdictions including the US, UK, Australia and Hong Kong.

Why doesn’t the Prosecution only follow prevailing public opinion, or only act in the victim’s interest?

The Prosecution is actuated by public interest, not popular opinion. As a representative of the public, the Prosecution conducts prosecutions for the good of the public and in the name of the public, even if these decisions are not popularly received. The insulation of the Prosecution from popular and political pressures also ensures that influential Singaporeans are not let off simply because of their high social standing and/or political connections, and consequently, safeguards the fundamental principle that all should be treated equally in the eyes of the law.

Similar to opinions held by the public, the views of victims are persuasive but not determinative. There are cases where the victims do not wish for the accused to be prosecuted. These include domestic violence or sexual abuse cases, where the victim does not want to damage the relationship with their abusive spouses so that they could still cohabit together, or where the victim is fearful of shame and stigmatization. Even more blatant are cases where the accused pays a large sum of money to persuade victims to retract their claims. Despite this, even if victims are uncooperative, unwilling, or even hostile to the prosecution bringing charges against the relevant perpetrators, the Prosecution may still continue with the prosecution notwithstanding the victim’s personal wishes and interests. The accused has committed an offense against not only the victim, but Singaporean society in general, and the Prosecution must accordingly make them answer to the public.

Conversely, there are cases where the victim feels very strongly that the offender must be punished, but there is no public interest to be served by the prosecution. This ties in with our subsequent question.

Why would the Prosecution issue mere conditional warnings or press a lesser charge for offences that seem to constitute a more serious charge?

In short, the possible answers to this question include: no public interest being served by the prosecution, difficulties of evidence, and/or difficulties in establishing the requisite elements of an offence.

The prosecutors often adopt a sequential process in ascertaining whether one should be charged with an offence. Firstly, prosecutors spend much time ascertaining whether a criminal offence is committed. This often requires deep research into possible offences and is a “factual and legal exercise”. Secondly, evidence must be looked at to determine if it is admissible in court, whether it is reliable, and the weight that courts will give to said evidence. Thirdly, the prosecutors determine if there are “reasonable prospects of obtaining a conviction”. Fourthly, courts then examine whether the public interest demands that the person be prosecuted – not all people who commit offences are prosecuted, as the public interest may not be served because the offender is “a first-time offender, below 18 years of age, committed a minor offence, is remorseful, made amends, or is unlikely to repeat the offence”. This explains why a mere conditional warning might be issued for certain transgressions.

Furthermore, in some cases, difficulties arise as to issues of evidence or as to successfully establishing all the elements of a more severe charge. In the recent Orchard Towers murder case, Chan Jia Xing was originally charged with the murder of Satheesh Noel Gobidass, but his charges were subsequently dropped and he was issued with a conditional warning due to the difficulty in ascertaining evidence that he participated in the attack. Even for 5 of the other 6 other participants in the murder, the murder charges were downgraded to lesser charges.

The Prosecution’s discretion to downgrade or substitute the original charges for different charges or conditional warnings continue to reflect the limits of forensic science and evidence gathering, especially when it comes to cases of murder. In cases where a person has been killed, the court will “consider all relevant and admissible factors that reflect the accused’s intentions, such as the individual characteristics of the accused as well as the objective surrounding circumstances of the crime, including the manner in which the crime was committed, the nature of the acts, the type of weapon used, the location and number of injuries inflicted on the victim, and the way the injuries were inflicted”. But where there is a lack of evidence in support of the aforementioned factors, the Prosecution has little choice but to bring lesser charges that are more easily proved, or substitute it for conditional warnings.

Crucially, these above-mentioned considerations that play into the prosecutorial decision-making process are known only to the Prosecutor and not to the public. This is because the Prosecution is under no obligation to disclose his reasons for prosecuting in a certain way. The absence of such an obligation from Singapore’s criminal justice system will be critically evaluated two questions later.

What mechanisms are in place to ensure that the Prosecution does not abuse its powers?

Given the expansiveness and scope of the Prosecution’s powers, one may wonder what mechanisms serve to protect against abuse. One such mechanism is judicial review, where the exercise of prosecutorial discretion may be reviewed and assessed by courts.

In the case where an offender faces harsher charges than their co-offenders, this offender may challenge the constitutionality of his prosecution before a court, as his right to equality is enshrined by Article 12(1) of the Constitution. However, the burden of proof lies on him, as there is a presumption of constitutionality and legality with respect to prosecutorial decisions stemming from the doctrine of separation of powers. Therefore, it would seem to be rather difficult for accused persons to be successful in this endeavor.

As an illustration of this, in the notorious Yong Vui Kong drug-trafficking case, Yong challenged the constitutionality of his prosecution, as he was facing the death penalty while the Prosecution applied for a discharge not amounting to an acquittal (DNAQ) for the more culpable criminal mastermind, Chia Choon Leng, who orchestrated the heroin trafficking. However, the court held that the DNAQ was applied and issued for legitimate reasons such as Yong’s previous express of fear and unwillingness to testify against Chia, and the resultant paucity of evidence. In any case, Yong was not actually discriminated against as Chia’s DNAQ was initially also a capital charge and also did not prevent a future prosecution. Yong was ultimately unsuccessful in his constitutional challenge.

Therefore, given the difficulty of a successful judicial review, it is arguable that inadequate mechanisms exist to safeguard against abuse of prosecutorial discretion. Together with the previous question, this segues into the next question:

Why is there no obligation for the prosecution to explain their prosecutorial decisions for every case? Should such an obligation be imposed?

This question has been hotly contested in the public arena before. Consequently, the Attorney General’s Chambers (AGC) has released a press statement explaining why these requirements have not been imposed.

According to the AGC, the first reason why the Prosecution is not obliged to explain its decisions is because this would defy the principles of judicial deference by the courts to the AG’s discretion. This would “impair the performance of a core executive function designated in the Constitution”.

Secondly, an obligation on the Prosecution to explain their prosecutorial reasons and considerations would unduly delay criminal proceedings and undermine prosecutorial effectiveness. Thirdly and finally, the imposition of such an obligation may also incentivize dissatisfied offenders to frequently challenge their prosecutions in courts.

Whether the above explanations provided by the AGC are satisfactory is an open debate. In his article “Re-examining Prosecutorial Discretion in the Context of s300(a) Murder and s299 Culpable Homicide”, Nicholas Khong argues that the Prosecution’s obligation to explain their decisions need not extend to every case. For example, the obligation could be confined to murder and culpable homicide cases, in which prosecutorial discretion assumes elevated importance. This would dispel the concern of unnecessarily elongating criminal proceedings. Furthermore, even if frequent challenges to the courts do ensue, Khong argues that this could be justified on the grounds of the accused person’s “irreversible and unjustified loss of life or liberty” being at stake in the case of a prosecutorial mistake.

Overall, given the difficulty and low likelihood of mounting successful judicial reviews (as previously explained) and the life-or-death consequences of prosecutorial biases and mistakes manifesting in serious offences, perhaps the Prosecution should be obliged to justify their prosecutorial decisions under specified circumstances.

Why are prosecutorial discretion guidelines not released to the public? Should they be released?

In the same press release mentioned in the previous question, the AGC explained that the guidelines relating to prosecutorial discretion are not publicized to enable the AGC to retain flexibility to depart from the guidelines when justice demands as such. Furthermore, any guidelines that are eventually released would invariably be vague and uncertain, and cannot account for the nuances of each individual case. Conversely, if specific guidelines that identify prosecution priorities and areas where the Prosecution might exercise restraint were published instead, this could potentially “lead to an increase in offending in the latter areas as accused persons might then be incentivised to commit such crimes expecting that they probably would not face the full force of the law”. It is for these reasons that the AGC justifies why prosecutorial discretion guidelines should not be disclosed to the general public.

It is submitted that these explanations provided by the AGC are principled and satisfactory. The nature of prosecutorial discretion is such that it is not meant to be circumscribed by specific and inflexible guidelines; and if vague guidelines were issued, these would simply serve no practical purpose. Therefore, there is no self-defeating way to introduce publicly-disclosed guidelines.

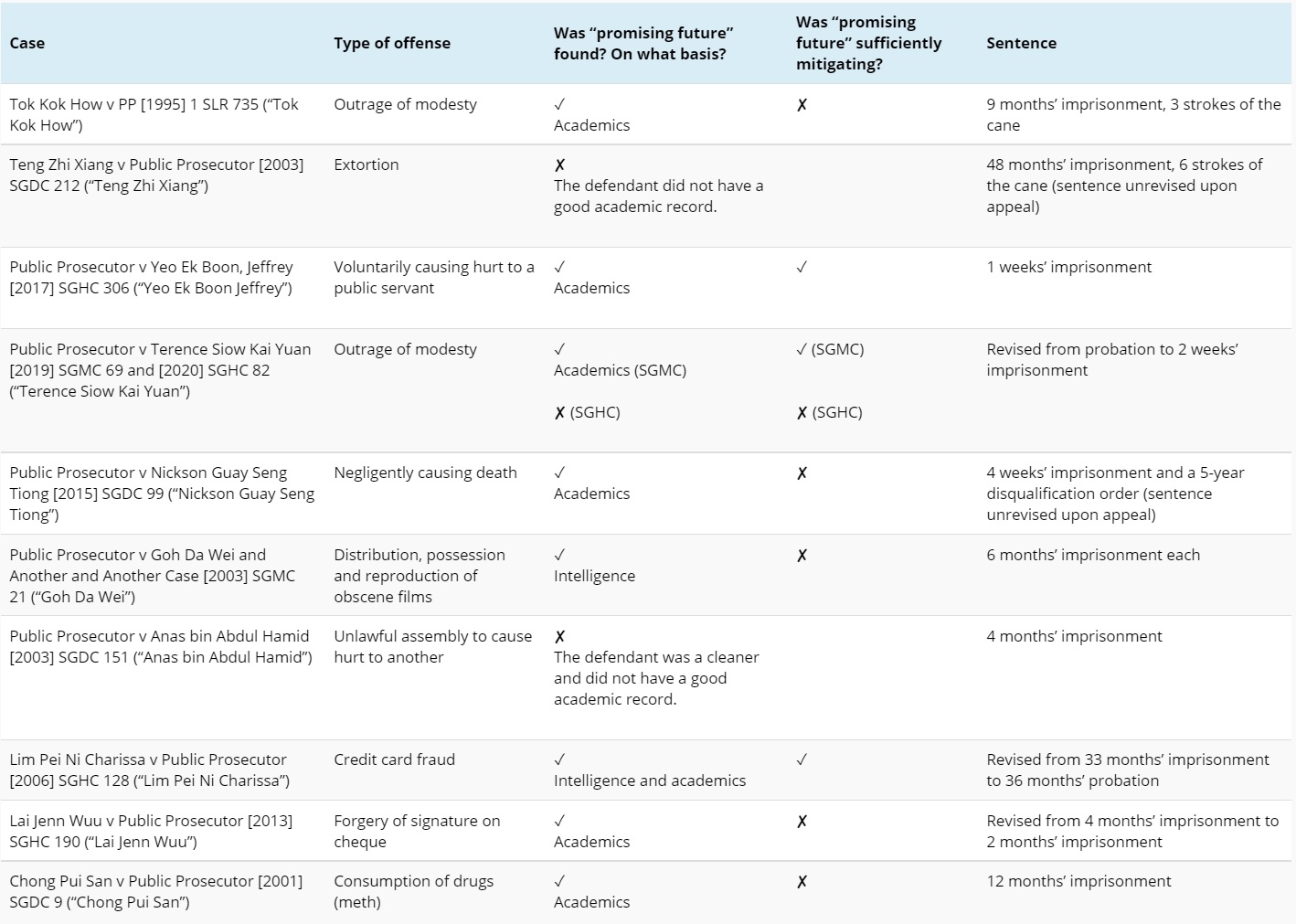

Furthermore, the prosecutorial considerations that Prosecutors regularly contemplate are not exactly hidden away and obscured from the public. With a simple read of a few relevant cases and news articles, lawyers and even mere laypersons can easily identify some factors that are relevant to the exercise of prosecutorial discretion, even in the absence of explicit guidelines.

Conclusion

In closing, the significance of prosecutorial discretion cannot be understated. It is an indispensable tool that imbues our criminal justice system with flexibility, and this article has sought to clarify its underlying principles and working mechanism. However, this article has also highlighted the potential inadequacy of existing checks and balances against abuses of prosecutorial discretion, and expounded on the potential need for reform with respect to the currently non-existent obligation on the Prosecution to explain their prosecutorial decisions.

Benjamin Goh & Tan Ying Qian

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.