How did you first become interested in criminal practice?

I mostly became interested in the criminal practice during the course of my work. However, I did very much enjoy studying criminal law during my first year in law school, even more so than some of my other subjects. I suppose the other thing is that when I was growing up, I watched some TV shows featuring lawyers, such as Matlock, a fictional lawyer who defended clients. These shows totally coloured my view as to what law entailed: I entered law school without any real understanding that a lawyer did anything else besides litigation. It was only when I got in that I realised that there are people who do things such as conveyancing, IPOs, trademark registration and so on.

Of course, my aforementioned first job was in the AGC, simply because I was on a PSC scholarship. There was nothing else I could do short of breaking my scholarship bond. Not that I was interested in breaking it at the time: I saw it as a good opportunity to see what working as a lawyer in the government’s service would be like. I very much enjoyed the work that I did – I would say the camaraderie in AGC is second to none, and perhaps even more so when I was there simply because of how small my unit used to be. I don’t think there were more than 50 to 60 prosecutors in the Criminal Justice Division back then, from the junior ones all the way up to the head of the division (excluding the AG, of course). Today, as far as I know, the division has more or less doubled in size.

One can really get a real sense of purpose in working as a DPP. However, not all of the attitudes that I had there were absolutely spot on. Most of us were probably underexposed to what things were like on the other side, and by that, I really mean the accused person’s point of view. While we would take into consideration mitigating factors when we made our prosecutorial decisions on what type of charges to prefer, the severity of the charges to prefer, the type of sentence and the severity of the sentence to push forward in court, it was not always easy to put yourself in the shoes of an accused person. Perhaps I was, in retrospect, more sceptical about things than would’ve been ideal. I say that now only with hindsight, having done criminal defence work since I left the AGC, and having had a lot of interaction with various clients for criminal cases.

When you say you were sceptical as a DPP, you mean to say that you were sceptical of the “other side”?

Yes. I would be sceptical about the extent to which an accused person could be said to be a certain way, perhaps less malicious than I believed at that point in time. Now I have seen clients go to jail for many years: in one case, just because they had helped to guarantee a friend’s illegal loans from a loan shark, had gotten harassed when a friend didn’t pay up, and misappropriated money from their employer just to make good on that guarantee, for a loan that they did not even get one cent’s worth of benefit from. And now, they are in jail for a very long time. Of course, the jail sentence is a lot less than if they had misappropriated the money to buy luxury goods. Still, you can see that oftentimes the motivations of accused persons are not always as terrible as one might think.

Besides this shift in perspective that you just described, were there any technical challenges that you faced during the switch from a DPP to a defence lawyer?

Absolutely. As a prosecutor, you do not have to do any “running” wherever investigations are concerned, other than thinking and asking for it. You can ask the police to perform various tasks for you: this is all part of their role in the criminal justice system. If you, as a prosecutor looking at the files, feel as though certain witnesses need to be interviewed, or that some other documents need to be reviewed (telephone records etc.), the police will get it done for you. There is no such comfort for a criminal defence lawyer. Either you do it on your own, or you get your client to get it done (of course within the limits of your client’s ability). For example, if you want telephone records between A and B, whom you suspect have conspired to frame your client, you have no legal right to get that as a lawyer for the accused person. However, the police do have the statutory power to get any document that they want. You will never get the document that proves that although A and B profess not to know each other, telephone records show that they have been speaking to each other once a day for a week before they made a police report against your client. I think that is one major change.

I don’t think I have ever had to face a huge moral dilemma in that sense as it’s pretty straightforward for me. If the client is guilty, we do what we have to do to help the client get an appropriate sentence. In cases where I have claimed trial for the client, the instructions to me have been that from the start they deny what they did, and I had no reason to disbelieve them. I think you’ll learn when it comes to professional ethics later on for your bar exam that by and large you take your client’s instructions at face value, unless it is apparent on other evidence that your client is not telling the truth. I don’t think I’ve got a lot of other things to say about differences between working or one side or the other. The other aspects of the job are pretty much the same: you still cross examine the witnesses, and you still give closing submissions in a trial, no matter which side you’re on.

Perhaps, however, there is one more difference in relation to trial, where the prosecution has the police statements of clients and various witnesses, and you have no such statement of the prosecution or witnesses. Through the new criminal discovery process that came about with the last major revision of the CPC in 2010, you now have access to your client’s previous statements to the police. However, you don’t have the previous statements of witnesses, and while the prosecution will probably give you (or your client) hell during cross examination when they point out how every little aspect of their testimony in court is different from their testimony or their story in their police statements, you don’t have that privilege of doing the same to the prosecution’s witnesses because you don’t have their witness statements, even if their witness statements might be different from the evidence that they give in court.

The Court of Appeal has ruled that the prosecution has a duty outside of statute to give materials to the defence that would materially contradict or undermine their case. But it’s all a “good-faith” kind of duty. There’s no real way to enforce it because you don’t even know what they’ve got in the first place. If they’ve got the complainant’s statement saying that when she was sexually assaulted her left breast was squeezed, but in court she says it was her right breast that was squeezed (a very fundamental difference), you would not be able to exploit that. Whilst a very strong case could be made that that kind of material should be disclosed to the defence, so it could be used in the interest of justice to highlight to the court that the complainant’s version of defence is not entirely sound, you are in no real position to tell whether or not that kind of information has been suppressed by any individual prosecutor.

This is not a satisfactory state of affairs, and I have, during trials over the last few years, clashed with the prosecution on this, taking issue with the way the charge was framed, initially, to how it was amended later on. So, using this analogy, it would be you (the accused), did molest this complainant by touching her left breast on this day at this place and at this time. Halfway through the trial, because the complainant changes from left breast to right breast, the prosecution would ask the court for permission to amend the charge, and I might have in a situation like that said that this suggests that she did once say that it was her left breast, so I think we should have a look at her statements to the police. The prosecution declined to give those documents to me, and we had to argue it out in court until the judge finally ruled that she would look at it herself, without showing it to me, to determine whether or not there was an inconsistency such that the prosecution would be compelled to give it to me. Eventually, the judge looked at it and decided it wasn’t that material, so that was that: I left it as it was without having seen what the document contained.

So you’re saying: trials are often skewed too far in favour of the prosecution, and that this is not a satisfactory state of affairs?

I feel you’ve got to understand that they (the prosecution) have a heavier burden of proof anyway, where they have to prove a case beyond reasonable doubt, as opposed to on a balance of probabilities where the court only needs to say, in a civil case: on a balance of probabilities, I think A is just a little bit more credible to me than B, so I think A is telling the truth. This does not work in a criminal case. If the complainant is just a little bit more credible than the accused person, the right thing to do would be to acquit and say that the charge has not been proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

So, it does make sense that they have more things stacked in their favour, so to speak. But I think a little bit more could be done, especially with regard to this problem of disclosure of potentially damaging materials by the prosecution, which is one aspect I think we could do better in. If you speak to enough criminal practitioners, you will realise that they will all tell you that clients aren’t always telling the truth. Not that it only applies to criminal cases, it also applies to civil cases. The move toward video recording of police statements is currently in progress, and I think the plan to enact this change may have been announced some time back last year or even the year before. I think it’s not that easy to implement, and we all understand the government’s perspective on this. I have to qualify that I do know more than others because I am part of the Criminal Practice Committee of the Law Society’s delegation that interacts a lot with the Ministry of Law on all these matters. We understand their problems, and we’re here to help by giving our input on how things can be tweaked for the better.

That’s not to say this will eliminate all possible allegations of impropriety when it comes to statement recording. All it does is that it rules out what happens when a statement is being recorded. You can’t prevent a threat, inducement, or promise being made at night when the suspect has been brought back to the cell. At the end of the day, you have to ask yourself: do you want to end up in a situation where because the odds are stacked against the prosecution, you have so many instances of sexual assault not being proven, or do you want to give the police and prosecution a little bit more authority and power such that you have more convictions for the guilty? I don’t know if in your study of criminal law so far, you have gone into concepts such as the due process model and the crime control model. That is a simple way of stating the two extremes: one is entirely authoritarian where you make sure you suppress crime as much as possible, while the other is where you give suspects their full rights, and the system is entirely fair for them, but inevitably you get more convictions in the crime control model and more acquittals in the due process model. Every society has to decide for itself where it wants to sit. It’s clear in Singapore that we are closer to the crime control model. It drives legislation and the attitude of the prosecution. But in terms of process, most of the time I would say that accused persons are given every right, with some exceptions where for example they are deprived of access to a lawyer.

You will probably learn more about this in your second year when you learn more about constitutional law. But yes, there is really no right or wrong answer on this. I would say that I am reasonably satisfied with the present state of affairs, although there is definitely some room for improving the system. All the stakeholders are trying their best to work to improve the system.

Have you ever had a client placed on death row?

Yes, but not for long. The charges were dropped to non-capital charges. It was a murder case, and after I sent in representation, after a few months the charges were dropped to a lesser charge of culpable homicide. So from that point onward, the client was off death row, so to speak. He wasn’t out of the woods, by any means, and we went for trial after that, and we got an acquittal even on the culpable homicide charge, and a conviction on a lesser charge. I won’t say more about this now, because this case is still under appeal right now by both sides: the prosecution, who believes that he should still have gotten culpable homicide, and us, because we think that the client shouldn’t even be found guilty of that lesser charge.

The closest I have ever come to a death row situation has been as a prosecutor. There was one drug trafficking case I did where the accused person was facing a capital drug charge. That was my one and only brush with the death penalty, I would say. I have actually consciously tried not to take on such cases, remembering how I had felt, perhaps, when my colleague and I got a successful conviction, and the judge stood up to pronounce that he could only sentence him to the only sentence that he could pass under law, which is the death penalty. So I think it took me a good ten years out of AGC before I took on this case. But to be fair, when I decided to take on this case, based on what I knew of it, I didn’t think that a murder charge would stick anyway. I was confident then that we would soon be able to convince them to move away to something less severe. Unfortunately, it seems things didn’t move away far enough, and therefore we had a big fight about it. Going forward, we’ll have to see where things end up.

How do clients typically react when you break good news of an acquittal or bad news of a conviction to them?

Some of them are overjoyed are relieved (for the good news). For the bad news, we’ve already prepared them and given them proper advice on what the possible outcomes and worst-case scenarios will be. We paint what we think is the likely outcome and tell them what the reasonable worst-case scenario is and what is the reasonable best-case scenario, what are not likely but absolute worst case, and what are not likely absolute best-case scenarios.

One thing I learned though, is that it’s not good to be too successful in a particular case sometimes. I had a case where a young guy who was in full time National Service was driving his vehicle over the weekend and he had an accident with another car and someone died. The passenger in the other car, who was not wearing his seatbelt, passed away. I managed to get a fine for him, instead of a jail term, which these days, with recent judgements in the last few years, might not be the case because sentences have increased for such traffic negligence cases. But when it came to the disqualification period, I manged to convince the court to disqualify him for one year only, when you would think a three to four-year disqualification period would be more appropriate for him. It was better than I had hoped for, but at the same time I had a sinking feeling that this was not going to be the end of the matter. True enough, the prosecution appealed, and this time, the High Court judge hearing the appeal was a lot more circumspect and increased the disqualification period to five years. So it was really a huge waste of time and money. The judge should just have passed the more appropriate sentence the first time round instead of just, ironically, being too persuaded by me, such that he gave too lenient of a sentence, a sentence that I would describe as unreasonably good.

In the same vein, one of the approaches that I take toward sentencing of a client is not to ask for a bare minimum slap on the wrist. I know that if I succeed, it’s going to be appealed against anyway, because I know that almost every judge, unless the judge is for some reason taken in by what is said, more so than one would expect, would just give short shrift to you. This doesn’t just apply to the defence, it applies to the prosecution as well. When the prosecution asks for a sentence that is too harsh, way more than what is reasonable, the judge is not going to be inclined toward your proposition and is just going to be listening to the side that is more reasonable. You want to always be perceived as more reasonable in order to be persuasive. But there’s a range of what might be considered reasonable, the low end to the high end. I would tend to peg my sentencing submissions at the low end of what is reasonable because I feel that that is justifiable, and I feel like that works a lot more than asking for something that the client says they want. When they ask for something unrealistic, you need to tell the client: ‘No, you’re not going to get off that easily because the last ten people in your situation did not get that, and you are not in a special situation. So there’s no reason why you should be treated any differently under the law.’ That’s about it.

Do you think there is a shortage of students who aspire to enter the criminal practice these days?

I don’t know about that because I don’t have that much interaction with the students in the local universities, but I can say that almost every intern that I have had has expressed interest in criminal matters that they’ve been tasked to help out on, sometimes even more so than on commercial matters. I don’t know if that is an indication of there being a substantial amount of interest, it could also be that they were interested in that already, hence if they knew that they got an internship with me they would be getting some exposure to that, and that’s why they sought me out in the first place. I don’t think I could say that I am aware of any lack of interest in criminal practice among undergraduates.

Do you think the public tends to overromanticize criminal practice?

Yes, I think maybe the public is heavily influenced by what they read. After all, you need to understand that the job of a journalist is to capture the attention of the readers, so they also are not interested in reporting about the really dry aspects of a trial. They only deal with the sensational and exciting aspects. You read about these, but there is probably a huge 80 or 90 percent that is a lot more routine.

Also, they tend to go for sensational crimes, as opposed to boring ones. However, some of the hardest battles can be fought in very non-descript cases, where the public wouldn’t otherwise have interest in it, but a lot is really going on in court itself. It’s difficult to write too much about commercial cases, except maybe in The Business Times, where from time to time you talk about really big fights and commercial disputes. The mainstream newspapers tend to focus on criminal cases. They are easier to understand. Not everyone can appreciate a dispute over a bill of lading, or a breach of warranties under a shareholder agreement. Some people do not even understand the concept of a shareholder of a company. But everyone understands what it means to steal, to rape, to murder, take drugs, and so on. So it’s very easy for them to think that things are a lot more exciting than they are. There are also a lot more criminal cases in Singapore: we’re talking thousands of charges every year. You can’t possibly write about them all. You may be reporting on trials that are sensational, but there actually only about ten percent of them go to trial. As for the rest, the accused pleads guilty, because they actually are guilty, and they have admitted to it from the start. In these cases, perhaps the police did a good job in arresting the right people, and the prosecution made the right call in charging them based on the evidence that the police found.

You were a student at NUS Law and part of the graduating class of 2000. What was life as a law student like back in the day?

It was a lot easier. I can say that anyone who went for an internship during the school holidays was probably viewed as a pariah. Like, “siao-on” or whatever. The prevailing mentality was along the lines of: come on, it’s the holidays, just relax! However, today, if you don’t seek out an internship, you might be viewed as a slacker, someone who is probably not serious about a career in the law. I must say that I am shocked by how much things have changed.

I don’t remember being too laden with assignments. Sure, there was preparation for classes, but it wasn’t too difficult if you split up the work with a few friends. You prepare this class, I’ll prepare for that other class, and we’ll share the notes after that. Certainly there wasn’t that mental pressure that all of you have these days. Maybe if you’re in NUS you feel that you are in a better position than someone studying overseas. Truth be told, you probably are, as a lot of employers in the industry are still having a very good impression of NUS graduates.

Exams were mostly closed book back then. Maybe you might have been able to get by with a good memory as compared to today when you might need to be a bit more analytical, possibly, but I think you can learn to be analytical, especially during the course of your work. I have to say that my time in the AGC has taught me to be very analytical of scenarios and analysing whether on the facts this falls within the prohibited conduct of the law. Sometimes it’s straightforward, like shoplifting, but other times you may have to consider some other obscure act, like whether or not something violates the Customs Act, for instance. Well, the Customs Act isn’t that obscure, but I’m just saying that perhaps it is less common relative to the Penal Code.

What about your extra-curricular activities in law school?

I spent some time doing those, but it was all recreational. I did ACTUS!, which was the drama group of law school. I was also involved in Law Camp for four years. I was one of the super seniors who was always helping out. I enjoyed myself so much during Law Camp when I was a freshman that I wanted to be involved in Law Camp every year after that. So that took up a lot of my midyear vacation time. That’s pretty much it, I think. I wasn’t involved in ELSA. There certainly wasn’t any Criminal Justice Club back then. I think one of the big things was the elections for Law Club. I wasn’t involved, but some of my friends were. I think it is a heavy commitment, in the same vein that being on the council of Law Society today is a heavy commitment. I spent a year as an honorary council member of the Law Society a few years back. Normally, elections are for two-year terms, but someone got elected and left after a year because she was going to an in-house job. If you weren’t going to continue practicing, you would have to step down from the council. I was recommended to take the place of that departing council member by some people on the council who knew me. I was brought on, I did a year, and I would say it was a huge eye opener, although it demanded a lot of commitment.

For students who are aspiring to become criminal defence lawyers, what attributes do you think they should begin to develop?

I think with the type of clients that you will meet in criminal practice, it would be good for you to brush up on your second language skills. In fact, if there is one thing that I could advise any law student, it would be: brush up on your second language skills. I have to speak Mandarin now at a level that I did not think I was capable of. I consider myself to be a barely competent Mandarin speaker, but in the course of my practice I have had to deal more and more with clients who are either exclusive Mandarin speakers or who are much more comfortable in Mandarin. In any case, you have to do what you can to ensure the client feels comfortable. So I guess I have had to bone up on my oral Mandarin skills. I suppose there’s no hope for my written Mandarin, but luckily, I can just leave that part to a colleague who is way more competent than me. But at least in your interactions with the clients, you have to speak well.

You should also be inquisitive, and it would be good if you could show some empathy to your clients rather than just looking at their conduct through very privileged lenses. I know not every law student comes from a privileged background, but the majority do, and even those that are less privileged are in all likelihood more privileged than most clients for criminal cases. I have encountered a client who has had to steal milk powder for his infant son, and that’s not something that you even have to contemplate if you are going to university. I think those are useful skills to have.

Nothing beats doing it for building up ability, so it would be good. Even if you want to do defence work, you can consider doing a stint in AGC because the training there is really good: you are immersed in criminal work over there. A lot of criminal practitioners do not do 100% criminal work anyway, myself included. Sure, there are some that do, but these lawyers are by no means the norm.

Try to get yourself a good boss as well. I’ve found that a lot of generalisations about what this and that firm is like is, as I have said, just a generalisation. What is far more likely to have an effect on your growth and development as a lawyer and your experience in practice is the person or persons that you are working for. It’s not always comfortable to choose, but you should always try to move yourself into that situation.

You will probably find that so many things in life probably just happen because of fate. It sounds scary to say that things are beyond your control, but I could not have anticipated that when I agreed to my father’s suggestion to apply for a PSC scholarship, that I would be in the situation that I am today. Even when I went to the AGC, I didn’t even see myself leaving the AGC, especially after my second year there, when I found myself starting to like the work and all that. Of course, the circumstances I was in then with the structure of the legal service was such that JLCs were very heavily favoured for promotions. This made the situation unacceptable to me and made me want to try my luck in the far more egalitarian environment of private practice. That situation exists to a much lesser extent today. If you’re good, they don’t care too much about grades when you enter the legal service as they believe you’ll do well anyway. Just being put on a particular file allows you to learn so much. Being introduced to a particular person who turns out to be such an important mentor or client for you next time, so many things happen that are just not within your control. You just have to adapt and best make use of the circumstances that you are in, and I would say that your attitude is critical. You’ve got to be willing to put in the hours to be interested in learning more, doing more, because you know that only by doing so will you become better and better. When I came out to private practice at Rodyk the last time, stuff came, and I would volunteer for this and that. It meant more work for me, but I wanted to do it as I knew that doing so would make me a better lawyer overall.

So yes, I believe these are the key things I can think about that would be important attributes for a law student who wants to be a successful lawyer. This actually applies across the board for all areas of law, not just for a law student aspiring to enter criminal practice.

What about one’s advocacy skills?

I’m a prime example of someone whose advocacy skills could improve. I was never a shrinking violet, but I was also never in any debating club and had never represented any school in any competitions. In fact, I had a very terrible experience in my second trial as a DPP. I was told off very severely by the judge for repeatedly doing the wrong things. During my first trial, I had a senior colleague to sort of chaperone me and provide advice, but on my second trial, I was entirely on my own. The case was not an easy one to handle, and I was up against two very experienced defence lawyers on the other side.

It was no joke: I wanted to quit. I was telling myself that I was not cut out for it, I had made a mistake taking the scholarship, and I wanted to leave the AGC, go into private practice and do corporate work. But then I realised that it wasn’t just a matter of paying off the bond. I would also have to resign and serve one month’s notice, meaning that even if I tendered my resignation, I would have to go to trial the next day and receive the same grilling that I was getting from the judge for making mistake after mistake, all because I did not know how to question the witness properly, and my advocacy skills were not good enough. That was the situation that I was in. I just had to soldier on when I realised I couldn’t get out of it and tried my best to do my job till the end.

About a year later, I was doing another trial, where I found myself internally criticising the defence lawyer for the same mistakes that I had made one year earlier in my second trial. It then struck me: I had actually improved as an advocate. It was a surprise to be sure, but a welcome one. Of course, I feel that I am even better today than when I was one year into my job. There is always clear room for improvement as long as you work hard and correct your mistakes. The only question is whether you will actually have the opportunity to practice that.

But one thing you must know, especially in private practice, is that written advocacy is probably much more important than oral advocacy. You may not be fluent when you speak, but if you can write a good mitigation plea to the judge, the judge can read it, and if the points you make inside are of good substance, I would say that would be quite ideal, and that is far more important than whether or not you are verbally fluent in conveying those points in court. After all, they are in writing, and the judge has to refer to them in considering what the proper sentence should be.

Life as a Public Prosecutor is often taxing and can be exhausting. Having taken on this difficult and rewarding role, Ms Charlene Tay candidly shared with us her experiences of working as a female in the profession. In addition, she gave valuable insight as to where she finds (and any aspiring Public Prosecutor could find) the motivation to persevere in this line of work.

On the practice of Criminal Law

In what ways, if at all, has your perspective on life changed after you started practising criminal law?

I have become more attuned to the plight of the under-privileged, and the mentally disordered. As a law student, I would say that I led a fairly cloistered life. I had never been exposed to the underbelly of society, or to the world of mentally disordered offenders.

The practise of criminal law has brought me face-to-face with such cases, and much more. I have encountered cases where a financially-strapped offender steals milk powder to feed her baby, and a schizophrenia offender who inflicts serious injuries on his family as a result of his mental condition. Such cases give me an insight into the plight of other members in society, and a greater understanding of why criminals offend.

In addition, the practice of criminal law has given me a sense of gratitude for what I have been blessed with.

How important do you think idealism is for a continuing career in criminal law? Does it help or hinder it? Has it played a big part for you personally?

Extremely important. It is all too easy to become overly cynical or pessimistic from working as a prosecutor. As a prosecutor, one is often exposed to the ugly side of human nature. One also witnesses the far-reaching consequences of a crime (and our charging decision) on the victim, the accused and their respective families.

I firmly believe that a sense of idealism is essential if one is to continue practising criminal law. As prosecutors, we have a special responsibility to uphold the integrity of the criminal justice system – we must ensure that prosecutions are conducted fairly and that convictions are safe. Also, we must hold firm to the belief in the value of our work, and the role we play in keeping Singapore safe. Without this sense of idealism, the practice of criminal law would become mere drudgery.

On Day-to-day life as a DPP

Could you describe a typical day at work?

A ‘typical day’ at work would depend very much on what I am busy with at the moment. If I am engaged in an ongoing trial, I would come into work, do a last minute check of all the documents that I require at trial, and go off to court for the day. Lunch would probably be spent poring over what transpired at trial in the morning, and assessing if any of these require follow-up before trial resumes in the afternoon. Thereafter, in the evening, I would return to the office to consolidate my questions for the next day and deal with any other issues that the judge may have directed that I follow-up on. I would also take a quick scan of my email inbox to make sure that there are no other urgent matters which require my attention. Given that the trial process is fairly demanding, I would typically put aside my non-urgent work for the duration of the trial and return to these after the conclusion of the trial.

Even where non-trial days are concerned, there is no fixed or typical format to my day. Due to my supervisory role, a good part of my day is spent in case discussions with junior prosecutors. These can range from basic issues such as how best to draft PG (plead guilty) papers, to trial strategy, sentencing positions and vetting written submissions. At the same time, a significant proportion of my time is also spent drafting my own documents, and interviewing witnesses for upcoming court cases.

Being in the AGC must involve long hours and hard work. How do you decide when to step away and take a break from it?

At the outset, I think it is important to remember that work is akin to a marathon, and not a sprint. I approach my work with consistency and diligence, but also recognise the importance of finding an outlet to relieve work stress. To me, this can take a variety of forms ranging from lunchtime gym sessions, playing with my children after work, to late-night baking in the wee hours of the morning. I also make a conscious effort to set aside time for a family holiday twice a year, so that I return to work fully refreshed.

Have you ever thought about entering private practice?

I have thought about it, but it’s not quite my cup of tea. I feel like I can make more of a difference with my work in chambers. Also, chambers provides more flexibility — it’s quite hard to do criminal work as a mainstay in practice since it’s always driven by client demand.

However, I do think the legal service provides a diverse range of options and if you’re interesting in private practice, you don’t have to be pigeonholed into being a prosecutor for the rest of your whole life. There are many people who have rotated to different roles and enjoyed it more there as well.

On life as a female DPP

Have you ever felt the need to handle certain situations differently because of your gender? How did you respond to these situations?

Not entirely. By and large, I would like to believe that it is an individual’s personality (rather than his / her gender) that dictates how he / she handles a particular situation.

That said, I recognise that gender differences do sometimes account for the different ways in which a prosecutor conducts witness interviews and assesses a witness’ credibility. For instance, a female prosecutor may be able to build better rapport with a female victim of a sexual offence. In such cases, while there is no hard and fast rule, the female prosecutor in the team would typically be the one who leads evidence from the victim in court.

A Bird’s eye view on the criminal law

As a female practitioner, are there certain trends within our criminal legal system which you are concerned about or looking into?

As a mother to three young children, I am especially concerned about the ready accessibility of the Internet to young children. Increasingly, children and adolescents are exposed to sexually explicit content on the Internet and social media. Sexual offenders have also exploited the Internet as a means of befriending underaged victims.

More should be done to ensure that our children receive proper sex education both at home and in school, and to keep the channels of communication between both parents and their children. This will hopefully help to reduce the likelihood of children falling prey to sexual predators online.

Are there any cases which are particularly emotionally draining?

Cases involving sexual offences are always more emotionally draining. It is difficult to assess the credibility of the victim especially if we have to ask them to relive their traumatic experiences. It is understandable why they would be hesitant to share. There are also cases with horrific circumstances such as accidents and homicide which will require us to look through some very graphic evidence.

What are the factors in consideration that affect how you decide to charge someone?

Things are often not so simple. Oftentimes some psychiatric issues must be taken into consideration. For example, why did the accused steal this particular thing? Was it out of greed? The considerations are often not purely legal, and it’s a very solutions-centric approach.

Even when you’re prosecuting an accused, you do feel the implications. You have to consider seriously the impact you could have someone’s life and not just in the short term — it could affect his prospects, his livelihood, his family. Prosecutors wield a lot of power in the choices they have to make and must take it very seriously. And it’s not just the accused that might be affected, but the victim might be affected as well if you do decide not to prosecute.

All in all there’s a lot to think about, and you have to see it as a big picture.

Out of all the cases that you’ve been a part of in your career (whether as a prosecutor or otherwise), which one has stuck with you the most?

In 2012, I was the co-lead prosecutor handling a case of attempted murder and aggravated rape. The victim was a foreign domestic worker (“FDW”) who had been raped by her neighbour, and who had allegedly been thrown out of her flat by her neighbour.

This case was personally significant for a number of reasons. First, it was the first High Court case in which I took on the heavy responsibility of co-lead counsel. Having only assisted in cases thus far, I now took on the primary responsibility of ensuring that the prosecution was conducted competently, and fairly. Second, I felt great sympathy for the victim, who had been sexually assaulted, and who bore both psychological and physical scars from the ordeal. As a result of having landed feet first during the fall, one of the victim’s feet had become significantly shorter than the other. The victim thus walked with a permanent limp and could no longer seek employment as a FDW. I developed a strong rapport with the victim and was able to convince her to testify in court. Third, this case threw up a number of unexpected surprises at the very last minute. Apart from having to make Kadar disclosure, I had to impeach my own prosecution witness on the stand.

On life in general

Do you have tips for law students in general?

I would advise them not to pigeonhole themselves into a certain area of law but to take a variety of courses to find out what they like. For me, I always thought I would end up doing corporate law despite taking a variety of courses. Regardless of the field that students end up in, it is important that they try their best and give their all in every project. As a lawyer, you can only add value when you take ownership and fully commit yourself to the task at hand.

Through your years of practice, have you noticed any differences in the type of law graduates entering the profession in the past and now?

For one, there never used to be any SMU graduates. Generally, younger graduates are very eager but are not always familiar with practice – things such as the life cycle of a case, beginning with the initial charging decision to the final sentencing position. For example, young lawyers may forget to place important aggravating factors into the statement of facts or may make certain concessions during trial that implicate their own cases. Sometimes, they may be unaware of issues in their own case.

What was your favourite module that you studied in school?

I can’t say that I had a favourite module as I took a variety of them and enjoyed them all. In reality, what you study in school may not have a necessary correlation to your final practice. However, if you do take a Master’s degree halfway through your professional work, it will be more likely to affect your specialisation.

Are there any particular personality traits that certain types of lawyers, such as litigators or corporate lawyers, are likely to possess?

People are likely to make certain generalisations but I think these can only be applied very broadly. For example, though people may assume that litigators are more likely to step up in court, there are some litigators who are happy to play a more secondary role by assisting their bosses. Corporate lawyers, on the other hand, are expected to be detail oriented as well as business savvy. These traits are also equally applicable to criminal lawyers. If someone is facing a hundred charges, you would want the evidence for each charge to be tabulated meticulously. Ultimately, it is whether you take pride and ownership in your work than whether you have a particular disposition that will determine whether you do well in the profession.

And just to end it off, any favourite legal shows?

I’ve been watching Making a Murderer recently, it’s quite interesting.

Written by Emmanuel Aw, June Ngian, Uma Sharma, Sun Fangda, and Yijie Zhang

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

This interview from 2015 has been re-posted from the old Criminal Law Website Project website.

Interview with Mr Sunil Sudheesan

Shortly after the “Criminal Law Art of Giving” dialogue, which centered on the access of justice in Singapore, it was our privilege to interview one of our esteemed panelists, Mr Sunil Sudheesan (Acting President, Association of Criminal Lawyers of Singapore), who shared his insights on pro bono and his experience as a criminal lawyer.

On mandatory pro bono for lawyers and students

Mr Sunil expressed that he was not very inclined towards the idea of making pro bono mandatory for both groups. In his view, mandatory pro bono is not practical if there is incongruence with the type of resources and the help the public required, each lawyer should use their expertise in their pro bono work. He was very forthcoming with his ideas and suggested, “corporate lawyers should do corporate law while criminal lawyers should stick to criminal law”. The latter can use their skills for CLAS (Criminal Legal Aid Scheme), instead of drafting a contract for a charity. Building on the point of practicality, a person who volunteers would provide a better quality of advice and be more willing to put in his best, whereas mandated lawyers are more likely to do pro bono for the sake of going through the motion. Putting it simply, mandatory pro bono would cheapen the good intentions of volunteers. Furthermore, it will be even more difficult to differentiate between those who perform purely out of obligation from someone who is truly passionate about pro bono. Upon being asked whether increasing the number of practicing lawyers, and in turn reducing legal fees, would be a more sustainable method in increasing access to justice, Mr Sunil was very candid with his answer unapologetically disagreeing with the suggestion. He has instead proposed the usage of economic principles to regulate behavior, such as incentives and penalties.

He too voiced his concerns on the potential countervailing effect of mandatory pro bono for students. Mr Sunil provided a personal anecdote of his time as a Rag and Flag chair in 2001, where the “rebellious” law school then refused to build a float and opted instead to do community service as their senior batch had done. The community service saw to a healthy response rate from the freshmen batch. His story illustrates the unexpected effectiveness of peer pressure and he even hypothesized that if Flag was indeed mandatory, his peers might have reacted more negatively. To him, people cannot be forced to do “good” and there will always be those attempting to get around the pro bono scheme. While it can encourage people to do things with a good motive, he sees the scheme as a practical issue in which its intention may backfire. He later readily summarized the opposing views on this, acknowledging the stance where the ends justify the means. The justification of mandatory pro bono can be grounded in the overall need to increase the amount of pro bono work done to match the current needs in society. Mr Sunil then finally returned to his point that the public good may however be damaged by someone who is not focused on the cause thereby illustrating the tensions involved in the policy making in this area.

On whether law students should be actively encouraged to do criminal law

Naturally, law students would be encouraged by the romanticism of criminal law, where one is heroically “fighting for the underdog”. Yet when it comes to the nuts and bolts of practice, one would observe people moving away from criminal law as a result of the lack of paying work. He did not see a supply side issue but rather an insufficient paying demand to attract talent, which remains the systemic issue. He challenged us to consider the frequency of cases in where more the affluent commit crimes. On top of that, the affluent are still inclined towards hiring senior counsels who may have a different way of handling criminal trials. This is as evinced in the recent City Harvest Church case for criminal breach of trust. Mr Sunil expressed his opinion that crime is often driven by economic reasons and may be reflective of deep-seated social issues. Venturing beyond the scope of law, he discussed the need for efforts to solve crime at the root level, passionately breaking down the factors (e.g economic motivations) one could consider in understanding and addressing crime. Particularly, Mr Sunil highlighted the fact that Singapore has been struggling with the drug problem for years. The effectiveness of the current punishments i.e death penalty or jail sentencing remains to be addressed.

On special attributes required of a criminal lawyer

Criminal law requires the litigator to be very sharp, breaking down everything to an elemental level. This applies to corporate lawyers as well, who need the ability to see the bigger picture and fix a contractual problem. Yet the question of sustainability also arises. He gave the example of environmental law which may not be a commercially viable area of practice. In choosing the right field, practicality has to drive a person as well.

Further, Mr Sunil mentioned that one should also have drive, passion in fighting for the underdog and the keen desire to address unfairness. Bestowing us with even more personal anecdotes, he explained the difficulties faced in reaching a just outcome for a criminal case and in the interactions he has had with the courts, much to our interest. He also cites his privileged position as Mr Subhas Anadan’s nephew in gaining the experience and role as acting president of ACLS to better help clients.

Mr Sunil’s passion for his work is undisputed, traits which undeniably make him one of the best criminal lawyers in Singapore. NUS CJC would like to thank Mr Sunil Sundheesan for his time and meaningful insights.

Interview by Teresa Pereira, Kenji Lee and Erica Phoon

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

This interview from 2016 has been re-posted from the old Criminal Law Website Project website.

Recently, NUS students had the privilege of speaking with Mr Kalidass as part of the CJC Battle of the Sexes Dialogue. Mr Kalidass graduated from NUS Law in 1997 and went on to teach in a private law school. He then proceeded to join the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC) for a remarkable total of 12 years, with a short stint as a legal counselor, before going into private practice. He is currently a Senior Associate in Trident Law Corporation.

We have attempted to document our conversation with him on the exhilarating art of Criminal Law practice – both in the public and private sector.

In the Chambers

Mr Kalidass credited his vehemently pleasant experience in the AGC to his mentor, Mr Edmond Pereira (former DPP, State Counsel and District Judge). He recalled how having a mentor in practice is cardinal in terms of guidance and direction. “The AGC is a great place to start!” Mr Kalidass shared with us on how the challenging work and close supervision amounted to a great experience in the AGC.

The Big Switch

Many concerns float around about the imbalance on Defence and Prosecution fronts. Mr Kalidass submitted that “supply and demand dictates” and currently, there is a steady equilibrium. There would be more problems if there were deliberate shifts. But, owing to the ebbs and flows of the quotidian legal market, switches between the two sides happen regularly. Mr Kalidass himself joined the private practice after spending significant time with the AGC.

On being a Public Prosecutor vs Private Practice

When asked about the difference in being a Prosecutor and a Defence lawyer, Mr Kalidass had interesting insights. He first shared, with much wit, that the first difference was in how he made the switch from submitting aggravating factors to mitigating factors. Mr Kalidass reflected on how his experience with the AGC benefited his perspectives when working in private practice. In the AGC, a lot of material was easily accessible but as a Defence counsel, documentation and information had to be sourced for. Undeniably, this was a challenge. Compared to his work in the AGC, a lot of his work in private practice involved getting to know his clients on a personal level, for they could only be assisted if they could be understood. While he knew that the change would not be easy, he truly enjoyed it. He shared heart-string-tugging and campfire-warmth-inducing stories on how his work touched and changed the lives of his clients and their families. “It’s a privilege to be able to do it”.

In any case (pun unintended), there is always so much more to learn in practice that what was taught in school. Professional conduct, litigation and criminal practice skills, are just a few of the many things. After all, “service is where your heart lies”, as Mr Kalidass astutely put.

The Criminal Justice Club is incredibly thankful for Mr Kalidass’ presence at our dialogue and the sharing of countless thought-provoking experiences. We hope that readers were able to vicariously experience Mr Kalidass’ passion for Criminal Law through this short excerpt. Stay tuned for more interesting dialogue sessions organized by the Criminal Justice Club!

Written by: Uma Sharma

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

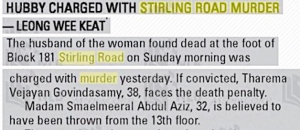

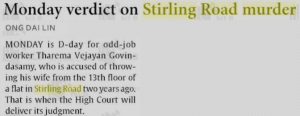

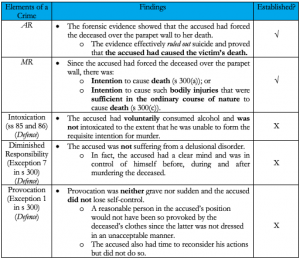

On finding the deceased inebriated, the accused became angry and began to assault her. He dragged her to the top of Block 181 before causing her to fall over the parapet wall onto the ground below.

*AR + MR + Absence of Defence (AOD) = Conviction

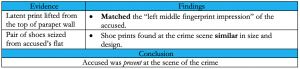

Prosecution’s Forensic Evidence

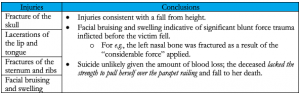

The prosecution relied heavily on the autopsy, bloodstains, fingerprints and shoeprints to make its arguments.

Performed by Associate Professor Gilbert Lau (“Professor Lau”) of the Centre of Forensic Medicine of the Health Sciences Authority (“HSA”), the forensic pathologist found the following injuries (amongst others):

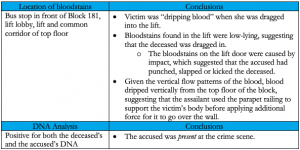

Forensic examination of the bloodstains and DNA analysis was conducted by Dr Tay Ming Kiong (“Dr Tay”) and Ang Hwee Cheng (“Mr Ang”) of the HSA respectively.

Fingerprint analysis was conducted by Mohd Yazid bin Abdullah (“Mr Yazid”) while shoeprint analysis was conducted by forensic scientist Chow Yuen San Vickey (“Ms Vickey”).

Judgment

From the very outset, Justice Tay Yong Kwang (“Tay J”) noted that positive blood swabs matching the accused’s DNA were found at the crime scene. This piece of forensic evidence was pivotal in placing the accused at Block 181 and its vicinity on 1 July 2007. It also proved that the accused had met the deceased.

In light of the damning forensic evidence and the inapplicable defences, Tay J thus convicted the accused of murder and sentenced him to the mandatory death penalty.

[Case Commentary written by Hariharan Ganesan]

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

The British government also established the Chinese Protectorate which was responsible for the welfare and provision of assistance to newly arrived Chinese immigrants. Over time, the Chinese Protectorate was seen as a practicable resource for immigrants to tap on in order to resolve their problems, as opposed to turning their problems in to the secret societies in hopes of achieving a resolution which was hitherto widely seen as their best alternative. This removed the impetus of many immigrants from joining secret societies and irrefutably had a hand to play in the eventual decline of secret societies.

It would be erroneous to mistake decline for eradication, however. The Societies Ordinance merely forced existing societies to go underground. This meant that they continued to exist in smaller and more inconspicuous forms. This period after the end of the 19th century saw the rise of groups such as the Malay-dominated OMEGA (Orang Melayu Enter Gangster Area) gang and the female-dominated Red Butterfly group. While gang activity has been actively and heavily curtailed by law enforcement, secret societies were never removed. They were removed only from plain sight. This brings us to the present day.

What do secret societies look like today?

Secret societies continue to exist today, albeit in lesser prevalence. The most eminent of them all, the Salakau, which means ‘369’ in Hokkien, is known to take part in many illicit activities and many of their members have been convicted for crimes such as rioting and extortion. They have been traced to many modern gang incidents such as the Bukit Panjang slashing and the Downtown East slashing. Another notable incident that many will remember is when Tan Chor Jin, nicknamed the One-eye Dragon, performed a gangland-style shooting of a nightclub owner and was subsequently hung for his act of murder. Tan was a member of Ang Soon Tong, a gang which continues to exist today.

Police efforts have also been stepped up to curtail the power these gangs. The police branch has a Secret Society Branch (SSB) which is set up primarily to suppress and eradicate such gangs by way of, inter alia, surprise raids and targeted investigation. The Organised Crime Act of 2015 accords power to the public prosecutor to confiscate assets obtained from criminal activities before sentencing. This prevents the accused from having the financial freedom to jeopardise or interfere with investigations. Education and outreach programmes are also conducted by the Police to educate impressionable youths who think that gangs are cool and are susceptible to falling to the temptation of joining one. The Ministry and Social and Family Development conducts youth outreach programmes, as well as intervention programmes, to discourage youths who have been affiliated with gangs from going any further. This multi-pronged approach has helped to greatly suppress gang activity in Singapore.

It is crucial to keep in mind that secret societies have evolved with the changing times as well, however. While the threat of gangs operating physically has been, for the most part, neutralised by strict legislation and comprehensive preventive efforts, we begin to see a new face of organised crime in the form of organised cyber-crime. An example that quickly comes to mind is the cyber-attack on the Ministry of Defence in 2017, where personal details of military personnel were taken and leaked by hackers.

While Singapore has yet to see the emergence of well-known organised cybercrime gangs to the notoriety of some international groups such as Cobalt Cybercrime Gang and Lazarus Gang, experts and law enforcement say that it is a growing threat. Furthermore, secret societies have been making use of the Dark Web to access online markets in order to sell illegal items such as drugs and firearms. Mr Rick McElroy, a strategist at digital security firm Carbon Black, said that the Dark Web “allows for criminals with little technical knowledge to become cyber criminals faster and with better efficiency”. Using both the Dark Web and a series of encrypted websites, these sales and the people behind these sales cannot be easily tracked by authorities. If you thought that combatting secret societies was difficult, how intractable of a problem is the genesis of these ‘invisible’ societies? The wielding of parangs may have been replaced by the clicking of a mouse, yet the effects to society are not any less deleterious. This new face of organised crime is one that rightfully deserves more attention and we should expect that the authorities will have their hands full coming up with a strategy to counteract such a potent threat.

Final words

As it turns out, those of us who believed that Singapore is free of triad activity are regrettably mistaken. It would be a graver mistake, however, for any of us to think that the secret societies of today look and operate like those of yesteryear. As criminals learn and adapt, so must the rest of us hoping and working for a safe and secure society.

David Chao and Stephen Yeo

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

BEFORE YOUR ATTACHMENT

1. We will link you up with the respective external parties (i.e. either the CLAS Office or the private firm lawyers). Once you are connected, you can expect to sign confidentiality agreements or non-disclosure agreements.

2. Depending on your project, we will also add you into the respective Telegram groups so that you are connected with your attachment partners, a CJC-CLAS Committee member and/or past interns/externs.

3. Please prepare yourself by doing the following:

DURING YOUR ATTACHMENT

1. Put your best foot forward and make the best use out of your attachment. Stay proactive and be responsible.

2. Diligently keep track of your Pro Bono hours and record them in your timesheet.

• Any sort of training, orientation, briefing cannot be counted as pro bono hours (unless otherwise stated). To find out more about what counts a pro bono work, kindly refer to http://www.sile.edu.sg/pdf/Probono_Criteria_and_Guidelines.pdf.

3. When working on research or drafting tasks, you can refer to the following documents for some guidance:

– CLAS Manual

– NUS CJC-CLAS Handbook

*These documents will be shared with you privately.

4. If you run into any problems (e.g. assignment trouble, missing partners, silent mentors, etc.), feel free to approach the CJC-CLAS Committee or any seniors that we have put you in contact with.

AFTER YOUR ATTACHMENT

1. Thank your lawyer mentor for giving you the attachment opportunity.

2. Politely ask your lawyer mentor to sign (physically or digitally) your timesheet because they are not obliged to do so. 🙂

3. Key in your hours onto SNL.

4. Email a copy of your signed timesheet to [email protected] (However, if you choose not to submit your pro bono hours, that’s completely fine too! We will just assume that you don’t need the recorded hours.)

5. Job complete….unless there are issues with your pro bono hours.

HERE’S WHAT USUALLY HAPPENS ON OUR SIDE…

With these new frameworks put into place, its effectiveness can only be proven with time. We are optimistic and confident that NUS will be able to tackle the challenges ahead, with a safer campus for all being the fruit of its labour.

Scott Yap and Johanna Lim

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.