CJC-F, CJC-F Announcements, CJC-F Understanding Forensics

DNA: The Silver Bullet to All Crimes?

DNA Technology in Crimes

In forensic investigations, we often hear the term ‘DNA’ constantly brought up by investigators as a formidable tool in solving crimes. What is DNA and is it really the silver bullet to unravelling criminal mysteries? Truly, the advent of DNA technology not only has enabled swift identification of criminal suspects, but more importantly overcome hurdles in both convicting the guilty as well as reinstating innocence. For instance, the Innocence Project in the United States of America, a national litigation and public policy organization dedicated to exonerating wrongful convictions via genetic testing, has achieved nearly 300 exonerations since 1992. On the other hand, forensic genetics has also successfully nailed masterminds behind numerous heinous crimes since its first use in courtrooms in 1986. DNA is a powerful technology that addresses the question of “who” is responsible in criminal investigations by associating suspects and dissociating innocent parties from scenes of crime. Furthermore, the contextual information of the source from which the DNA sample was obtained could also reveal “what” had happened, explained below in this article.

What is DNA?

Source: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/319818

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is the genetic material present in all living cells. It contains all the fundamental makeup of a living system necessary to define the structures, physiological properties and biochemical processes that occur in a human body. DNA is located in the nucleus of every cell, with the exception of red blood cells. It can be extracted from the blood serum, roots of hair, semen, bones, saliva, sweat, skin and other biological samples. The genetic blueprint of every individual, however, is unique, except for identical twins. Therefore, if the sample left behind at the crime scene can be detected and analysed, the information obtained could then be used to trace to the perpetrator.

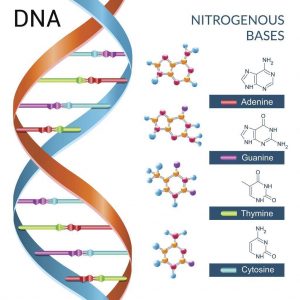

DNA profiling operates on the working principle of characterising specific repeated DNA sequences (also known as “short tandem repeats” or STR) in a genetic sample which are present in every human being. Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes, which are coiled up macrostructures of DNA. In each chromosome, a fixed position on the structure is called a locus where units of heredity (genes), are positioned within. Alternative forms of a gene that arise from mutation are called alleles. Within each DNA molecule, there are four building blocks – adenine, guanine, thymine and cytosine, which line each parallel strand of the macromolecule. Adenine pairs with thymine while cytosine pairs with guanine on complementary strands in a double helix. The sequences of the four nucleotides lining each strand bear underlying genetic information characteristic of an individual, which give rise to DNA fingerprints unique to that individual, allowing individualisation and identification to be done.

DNA Profiling in Criminal Cases

DNA Profiling in Criminal Cases

DNA profile matching rivets the interest of the masses and evokes the notion of a silver bullet in crime scene investigations, particularly in murder and sex crimes. After a crime has taken place, crime scene investigators cordon and comb the crime scene for physical evidence. If a potential weapon, such as a knife, is suspected to contain DNA, it is carefully collected and then sent to the DNA Profiling Lab in HSA to be analysed. The exhibit is first swabbed for biological samples, such as epithelial cells, before extraction of DNA is carried out on the sample. The amount of DNA present is then quantified followed by amplification via polymerase chain reaction (PCR). PCR enhances the sensitivity of DNA analysis by multiplying the copies of DNA given that the amount extracted from the sample is likely to be low. It also helps reduce the time taken to profile a sample and can be used with degraded DNA samples.

After which, the amplified PCR products are detected and transcribed into a DNA profile to be analysed and interpreted by a forensic geneticist. The forensic geneticist examines the DNA profiles obtained from the crime scene exhibit and that from the suspects by comparing 20 core STR loci. A statistical evaluation of the DNA profiles is then carried out to determine the likelihood of the DNA profile belonging to the accused versus somebody else randomly selected from the population. DNA profiles can be retrieved from the Combined DNA Identification System (CODIS), which is owned by the Singapore Police Force and managed by HSA. Finally, the forensic geneticist prepares a report and testifies as an expert witness when summoned in court.

Public Prosecutor v Tharema Vejayan s/o Govindasamy (“The Stirling Road Murder”)

Facts: On finding the deceased intoxicated, the defendant became angry and assaulted her. he then brought her to the top of a block of flats before causing her to fall over the parapet wall to her death. The accused was charged with murder under s 300 of the Penal Code (“the Code”).

Holding and explanation: Convicting the defendant of murder, the Court rejected the defence’s argument that the deceased’s ex-boyfriend, Manimaran, could have been at the scene. Since Manimaran had been previously convicted of theft, his DNA sample was stored in CODIS. His DNA was compared to the unknown DNA found at the scene but no match was found.

In contrast, positive blood swabs matching the defendant’s DNA were found at the crime scene, placing him at the block on the night of the murder. Other forensic evidence (e.g. fingerprinting) showed that the defendant had forced the deceased over the parapet wall to her death (establishing the actus reus). This gave rise to the inference that at the very least, the defendant had intended to cause such bodily injuries that were sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death (establishing the mens rea).

In the absence of any applicable defences, the defendant was thus convicted and sentenced to death.

DNA evidence obtained from a crime scene may serve several purposes aside from identifying individuals present at the scene. A DNA profile may be used by the police to conduct a database search to eliminate innocent suspects and narrow down to a smaller group to facilitate investigation. The profile may then be stored in the database which would be helpful in establishing links if the accused reoffends as well. This is premised under the Registration of Criminals Act (ROCA) which allows the police to record into the Registry of Criminals particulars including DNA from blood, head hair with roots or buccal swabs obtained.

Forensic geneticists may also be able to infer information from the candidate DNA profile, such as the colour of hair, skin colour and state of health, to expedite the process of culprit identification. The contextual information of where the DNA sample was recovered from could additionally shed light on the actual event that transpired during the crime and be vital in establishing the truth. Therefore, it is essential that legal advocates communicate and work in tandem with forensic scientists so as to bring out the utmost value of a DNA evidence to aid the case.

Public Prosecutor v Isham bin Kayubi

Facts: The defendant brought the two 14-year-old female victims to his flat under false pretences before raping them. The accused was charged with four counts of rape under s 375(1) and two counts of sexual assault by penetration under s 376(1) of the Code.

Holding and explanation: Convicting the defendant of all six charges, the Court reasoned that his semen was found on the first victim’s intra-vaginal swabs and on the front of the latter’s panties, this indicated that the accused and the first victim had engaged in the sexual acts constituting the charges. The DNA profile not only identified the perpetrator, but further corroborated an act of rape.

Since both the victims did not consent to the incidents, the defendant did not have any applicable defence. He was found guilty and sentenced to 32 years’ imprisonment and 24 strokes of the cane.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

References

- William Goodwin, Adrian Linacre & Sibte Hadi. 2011. An Introduction to Forensic Genetics, 2nd Wiley-Blackwell.

- Monjur Kader, Stella Tan Wei Ling & Sabrina Kuan Ling Li. 2011. The Use of DNA Forensic Evidence in Criminal Justice, 29 L. Rev. 35.

Authors’ Biography

Associate Professor Stella Tan has postgraduate qualifications in law and science from NUS, and a postgraduate forensic science qualification from the Henry C. Lee Institute of Criminal Justice and Forensic Science, where she graduated top of her class under the tutelage of Dr Henry Lee, a renowned forensic expert in the United States of America. Prior to joining NUS in 2018 as a full-time faculty member, she was a Deputy Senior State Counsel at the Attorney-General’s Chambers where she was the lead prosecutor for a wide range of cases, including murder, sexual assault and drugs, and later Director (Prosecution and Legal Policy) at the Health Sciences Authority (HSA), where she provided legal advice and practical training to forensic experts. Prof Stella Tan is currently the Director of the Forensic Science undergraduate and postgraduate programmes at the Faculty of Science. She runs modules in both the Faculty of Law and the Faculty of Science. The modules which Prof Tan teaches are as follows: LSM1306 Forensic Science, SP3202 Evidence in Forensic Science, SP4261 Articulating Probability and Statistics in Court, SP4262 Forensic Human Identification, SP4263 Forensic Toxicology and Poisons, SP4264 Criminalistics: Evidence and Proof, SP4265 Criminalistics: Forgery Expose with Forensic Science, SP4266 Forensic Entomology, FSC5199 Research Project in Forensic Science, FSC5101 Survey of Forensic Science, FSC5201 Advanced CSI Techniques, FSC5202 Forensic Defense Science, FSC5203 Digital Forensic Investigation, FSC5204 Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, FSC5205 Forensic Science in Major Cases and LL4362V/FSC4206 Advanced Criminal Litigation – Forensics On Trial. Prof Stella Tan is also the Principal Investigator of the NUS Forensic Science Laboratory, where her collaborators include the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Singapore Police Force and Central Narcotics Bureau. Her interest in nurturing students has won her Dean’s Meritorious Teaching Awards as well as the Best Supervisor award for Undergraduate Research Opportunities.

Associate Professor Stella Tan has postgraduate qualifications in law and science from NUS, and a postgraduate forensic science qualification from the Henry C. Lee Institute of Criminal Justice and Forensic Science, where she graduated top of her class under the tutelage of Dr Henry Lee, a renowned forensic expert in the United States of America. Prior to joining NUS in 2018 as a full-time faculty member, she was a Deputy Senior State Counsel at the Attorney-General’s Chambers where she was the lead prosecutor for a wide range of cases, including murder, sexual assault and drugs, and later Director (Prosecution and Legal Policy) at the Health Sciences Authority (HSA), where she provided legal advice and practical training to forensic experts. Prof Stella Tan is currently the Director of the Forensic Science undergraduate and postgraduate programmes at the Faculty of Science. She runs modules in both the Faculty of Law and the Faculty of Science. The modules which Prof Tan teaches are as follows: LSM1306 Forensic Science, SP3202 Evidence in Forensic Science, SP4261 Articulating Probability and Statistics in Court, SP4262 Forensic Human Identification, SP4263 Forensic Toxicology and Poisons, SP4264 Criminalistics: Evidence and Proof, SP4265 Criminalistics: Forgery Expose with Forensic Science, SP4266 Forensic Entomology, FSC5199 Research Project in Forensic Science, FSC5101 Survey of Forensic Science, FSC5201 Advanced CSI Techniques, FSC5202 Forensic Defense Science, FSC5203 Digital Forensic Investigation, FSC5204 Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, FSC5205 Forensic Science in Major Cases and LL4362V/FSC4206 Advanced Criminal Litigation – Forensics On Trial. Prof Stella Tan is also the Principal Investigator of the NUS Forensic Science Laboratory, where her collaborators include the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Singapore Police Force and Central Narcotics Bureau. Her interest in nurturing students has won her Dean’s Meritorious Teaching Awards as well as the Best Supervisor award for Undergraduate Research Opportunities.  Zheng Yen Phua is a teaching assistant for the Forensic Science programmes at the Faculty of Science. He holds an honours degree in science from NUS and is currently a doctoral researcher. The modules which he is actively involved in teaching are: LSM1306 Forensic Science, SP3202 Evidence in Forensic Science, SP4261 Articulating Probability and Statistics in Court, SP4262 Forensic Human Identification, SP4263 Forensic Toxicology and Poisons, SP4264 Criminalistics: Evidence and Proof, SP4265 Criminalistics: Forgery Expose with Forensic Science, SP4266 Forensic Entomology and LL4362V/FSC4206 Advanced Criminal Litigation – Forensics On Trial. He also received Honourable Mention as Expert Witness for the NUS Forensic Science Expert Advocacy Cup 2020.

Zheng Yen Phua is a teaching assistant for the Forensic Science programmes at the Faculty of Science. He holds an honours degree in science from NUS and is currently a doctoral researcher. The modules which he is actively involved in teaching are: LSM1306 Forensic Science, SP3202 Evidence in Forensic Science, SP4261 Articulating Probability and Statistics in Court, SP4262 Forensic Human Identification, SP4263 Forensic Toxicology and Poisons, SP4264 Criminalistics: Evidence and Proof, SP4265 Criminalistics: Forgery Expose with Forensic Science, SP4266 Forensic Entomology and LL4362V/FSC4206 Advanced Criminal Litigation – Forensics On Trial. He also received Honourable Mention as Expert Witness for the NUS Forensic Science Expert Advocacy Cup 2020. Hariharan Ganesan is a Y2 student at the NUS Faculty of Law. He is currently pursuing his interest in criminal law working as a research assistant for Assistant Professor Cheah Wui Ling. He is currently a Project Manager in CJC Forensics, heading the publication Initiations: A Glimpse into Forensics. Beyond school, Hariharan volunteers as a Silver Generation Ambassador, reaching out to Merdeka Generation seniors on the Merdeka Generation Package. In his free time, Hariharan enjoys playing squash recreationally.

Hariharan Ganesan is a Y2 student at the NUS Faculty of Law. He is currently pursuing his interest in criminal law working as a research assistant for Assistant Professor Cheah Wui Ling. He is currently a Project Manager in CJC Forensics, heading the publication Initiations: A Glimpse into Forensics. Beyond school, Hariharan volunteers as a Silver Generation Ambassador, reaching out to Merdeka Generation seniors on the Merdeka Generation Package. In his free time, Hariharan enjoys playing squash recreationally.