CJC-F Announcements, CJC-F Insights

About the prosecutors

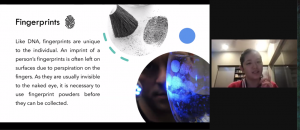

A fingerprint on a dusty windowsill – the sole evidence used in nabbing the accused of a housebreaking incident. “That case stuck with me because of how meticulous the crime scene experts were,” Ms Grace Lim recalls from her time as a young prosecutor.

“I wanted to be a police officer,” she also shares. However, her parents thought that it was a risky job. In turn, she applied for law school, and was pleasantly surprised that “mooting and cross examination were quite fun”.

Following a degree in law at the National University of Singapore (NUS), Ms Lim became a Deputy Public Prosecutor (DPP) at the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC), where she joined the State Prosecution Division, and was later posted to the Financial and Technology Crime Division. She then held an appointment of Director (Legal) at the Health Sciences Authority (HSA).

Currently, she takes on the role of a Deputy Director in the Crime Division of the AGC and specializes in financial crimes.

Also with us is Mr Eugene Lee, a senior state counsel at the AGC, now primarily prosecuting sexual crimes. He is concurrently an esteemed lecturer in forensic science at NUS.

When asked about his most unforgettable case involving forensic science, Mr Lee hesitates, “quite difficult to say”. At our insistence, he reveals that it was the first case he handled as a prosecutor, a grievous murder at the Drug Rehabilitation Centre. Provoked by the deceased over a game of table tennis, the accused covertly “sharpened his toothbrush into a sharp point”. It was then used as the fatal weapon which pierced the deceased’s carotid artery, regrettably leading to his death. “The blood spatter was all across the wall,” Mr Lee recalls.

On what was the most impactful, Mr Lee recollects words from the deceased’s family, “Thank you for seeking justice for my son.” “And that I remembered all my life. It is all about seeking justice for people,” he says.

Role of prosecutors

Although fiction and television might make it seem that prosecutors who specialize in a certain field will only be assigned cases in that cluster, the reality is much more fluid. A prosecutor who primarily does homicide cases can be assigned a sexual assault case, or even a financial corruption case from another cluster. “Even though I specialize in corruption, I have just been assigned to assist in a capital drug trafficking trial,” Ms Lim shares.

“While the subject matter of what we handle is different, the type of work that we do is really not that much dissimilar,” she explains, describing the way cross-handling occurs on the job. “We look at the files that come in and assess whether there is sufficient evidence collected by the police or other investigative agencies to make out the charge. Then we decide whether to charge, warn or take some other action against the offender. We render advice to law enforcement agencies as well,” she adds.

The only difference between being a prosecutor and a lawyer in a law firm, Ms Lim jokes, is that prosecutors cannot decline cases. Mr Lee qualifies this by adding that DPPs do so in special circumstances, such as when the accused is known to them. They would then declare the existence of a personal interest for impartiality’s sake. Notwithstanding such conflicts of interest, prosecutors generally do not decline cases, and are assigned cases based on “their level of seniority and how complex the case is”.

Use of forensic science in cases

Many cases require some degree of forensic science. The classic application of forensic science is common in homicide, drug and sexual offence cases, with digital forensics having a paramount role in modern investigations.

What exactly is digital forensics? Mr Lee summarizes it as investigations relating to mobile phones, email correspondence, social media and other digital platforms that likely hold valuable information concerning the case at hand. Not only will there be a sheer amount of evidence to go through, much of it is often irrelevant, making it an extremely tedious exercise. “Sometimes you strike a gold mine,” he points out, with the discussion of crimes captured in online correspondences, but such occurrences are rare.

Ms Lim also remarks, “Digital forensics is like a workhorse, we use it to plough through all the evidence and tie together the threads of different things one has.” The need to synthesize is thus imperative in digital forensics.

Ms Lim illustrates this with the case of Public Prosecutor v Ding Si Yang [2014] SGDC 295. Ding, the accused was found guilty of providing “girls” to three Lebanese referees in exchange for match-fixing. The incriminating evidence was collated by sieving through the match-fixer and referees’ emails and WhatsApp messages. It revealed how they were introduced to each other and the type of corrupt offers made. The match-fixer’s call logs were also used to corroborate how and when the girls were provided to the referees. As Ms Lim sums up, “The digital evidence in the form of emails, messages, and call logs were thus important evidence that helped to piece together and explain the purpose of disparate meetings between the key players.”

Undoubtedly, with the prevalence of smartphones, even in cases like murder and rape (which physical evidence predominates), one cannot exclude the use of digital forensics, with “phones now important in every single type of crime handled”.

Expert witnesses

In relation to presenting forensic evidence in court, the role of expert witnesses is vital. Prosecution evidence is for the most part processed by forensic scientists from HSA. Sometimes, external consultants are also involved. Before forensic scientists testify in court as expert witnesses, they have to be trained. “With their basic knowledge of law from the TV, they have to go to court and testify. That’s not enough,” Ms Lim says.

HSA has their own internal training to help expert witnesses better understand the court process, and the legal department also steps in to run mock testimony practices for them. “My role in relation to expert witnesses is really to advise them on the law and help them to understand the whole criminal process,” Ms Lim adds, providing an insight into her experience in training expert witnesses as a former Director of the legal department at HSA.

Apart from addressing questions expert witnesses often have, her role includes analysing the reports expert witnesses have prepared and predicting possible issues that might arise. More importantly, she arranges mock testimonies for the expert witnesses. “They are trained in Science while lawyers are trained in law, and when we come together, we need to understand what each other is doing,” Ms Lim shares.

She then points out, “As legal counsel when we try to do the mock testimony for them, we have to come out with the facts. Otherwise, it is impossible to do any sort of examination-in-chief or cross-examination without a case theory.” This comes with the fact that the expert witnesses have no knowledge of the background of the case to ensure impartiality.

Perhaps the most important in a mock testimony is restricting the use of extensive technical jargon by expert witnesses. “Forensic scientists must be able to explain the concepts in a simple manner such that lay persons with no background in Science will be able to understand,” Mr Lee says. With the prosecution, defence and judges comparatively having a limited understanding of Science, it is essential for expert witnesses to explain their analysis in a simple manner.

However, “It is not easy for them because they speak to each other every day in jargon. Lawyers use the terms like ‘negligence’, and ‘ameliorating the damage’. It is the same problems that scientists will have,” Ms Lim remarks. Also, “Singapore is quite insulated in this aspect,” Mr Lee adds. “In the US, they have a jury system, and they are neither trained in science or law, so the explanation has to be simplified even further, or the jury will not be convinced.”

Moreover, expert witnesses have to deal with the pressure of being in court. As such, part of the training includes “making sure they are more confident, that they can explain themselves clearly and be unrattled by the barrage of questions coming in from different angles. There won’t really be concerns with the content of their work, but more of how they carry themselves in court. Little things to tweak their presentation, ensuring that their evidence comes across as convincing,” Ms Lim says.

Prosecutors also have a role in preparing expert witnesses. Mr Lee explains the process, “First, they come up with a report. After we read through the report and if we need clarification from them, we will set up an interview with them and ask them about specific parts and sometimes when we realize that the particular issue may be very complicated, we might ask them to create slides to help present that concept in court.” Certain aspects of their testimony are then evaluated, like the extent of technical jargon being used, how the results were derived and whether there is any possibility of mistake.

However, such discussions can only happen after the expert witnesses have done their analysis and written their final reports. “We only talk to them after that to understand what they are doing for the trial.” Notwithstanding the liaison between the HSA and the prosecution in prepping the expert witnesses for trial testimony, both parties still work relatively separately. Singapore’s criminal justice system is such that the scientists in HSA are insulated from the criminal investigations, so that they can maintain their independence in arriving at their scientific conclusions.

As Ms Lim explains, “It’s not like TV where you see the prosecutors, police and scientists sit together to discuss what to put in the report. Because they are experts, they have to have their own opinion and do the analysis themselves and be able to back it up.”

Challenges in the use of forensic science

In using forensic science as the basis for evidence, it is foremost imperative for everyone to come to the same understanding. However, it is often not the case. “People make a lot of assumptions about Science because if you know a little bit of Science, you kind of jump the gaps between understanding and assuming that if I know theory A, it should apply the same way to what the scientist is talking about that is kind of similar. But that may not necessarily be true,” Ms Lim says.

To this, Mr Lee concurs, illustrating this with a High Court case that he handled. “There was a lot of blood over. They swabbed for DNA, but there was no DNA. So the judge said, how come there is no DNA?” he says. The answer lies in the low proportion of nucleated white blood cells in blood available for DNA extraction. “The judge did not know this. A lot of assumptions are made about Forensic science because of CSI. Previous episodes of CSI are very inaccurate.” It is thus imperative for mock testimonies to be arranged so that scientists are aware of explaining the step-by-step process of their analysis, debunking any possible assumptions made.

To narrow the scope of discussion, we further explored the limitations of both DNA and pattern recognition evidence.

DNA evidence

The media quite glorifies the use of DNA analysis in solving criminal cases. Almost everything can be solved by a single DNA swab, with instant results. The reality, however, is quite different.

To begin, Mr Lee points out, “DNA is obtained from the nucleus of cells, and cells will die with exposure to bacteria, heat and UV lighting.” DNA evidence is thus ideally analysed as soon as possible. However, if HSA is overwhelmed with many cases and the submission of multiple exhibits, it will take a long time to process the samples.

To avoid compromising on the integrity of DNA, the evidence is stored in the fridge. However, this cannot account for how long the police takes to the find the piece of evidence, swab it and send it to HSA for analysis.

Ms Lim adds that with forensic evidence, there is usually a “trade-off between accuracy and reliability against how quickly the results can be obtained”. Rapid DNA analysis can definitely be done, but parties might be uncomfortable using such results in court. Explanations will have to be given to further convince the court that the results are reliable. Instead, a thorough analysis done over a longer period of time would most likely give fool-proof results.

Similarly, for digital forensics, a brief preview of mobile phones and hard drives can produce useful information. However, information hidden in encrypted folders or deleted can only be found through a fully digital forensic analysis where the information is put through a forensic software, allowing a complete investigation.

Mr Lee then advises that DNA evidence is not an absolute requirement in cases. “In the 90s, we did not use forensic evidence, we used confessions due to the limited forensic evidence one could obtain,” he explains. However, in the past decade, the focus shifted to the use of forensic evidence in court, where judges prefer objective evidence to verify the veracity of witness testimonies.

Mr Lee remarks, “DNA evidence has only one purpose – to link the suspect to the victim by the showing that the suspect was at the scene. Other than that, DNA cannot tell you what the suspect did, what time the suspect was there, and how long the suspect was there… In most cases, DNA evidence does not really play a crucial role that makes or breaks the case.”

He illustrates this with the case of Public Prosecutor v Wang Wenfeng [2011] SGHC 208, which he personally worked on. In this case, the accused’s DNA was not found in the taxi in which the deceased was killed. The defence then attempted to argue that the deceased stabbed himself, which led to his own death. However, despite the lack of DNA evidence, the accused was eventually found guilty of murder. Evidently, “Forensic evidence cannot be seen in isolation. It has to be seen in the wider context, regardless of whether it aids the prosecution or the defence.”

Pattern recognition evidence

Apart from DNA evidence which is perceived as the gold standard of forensic science, there are other forms of evidence, like pattern recognition. Pattern recognition evidence broadly encompasses fields like tool marks, bite marks, firearms analysis and even fire reconstruction.

The use of pattern recognition evidence is however controversial, with courts pushing for a statistical basis of such evidence, as can be applied to DNA. “Unfortunately, all the pattern recognition experts are largely unable to come up with such statistical basis, causing it to be termed ‘junk science’,” Mr Lee remarks.

A prime example is bite marks. Although Mr Lee highlighted that bite marks can be individualistic, Ms Lim points out that “It would be almost impossible to conduct a thorough study on the whole universe of bite marks, and thus a statistical analysis would be very difficult to do.”

Regardless, Mr Lee shared that bite marks may be relied on for elimination rather than specifically identifying a suspect as the accused. He specifically referred to the case of Public Prosecutor v Sundarti Supriyanto [2004] SGHC 212. In this case, there were bite marks on the accused, and three persons who could have inflicted them: the employer (deceased), a toddler and an 18-month-old baby. The accused claimed that the bite mark belonged to her employer, but after close examination, forensics experts ruled that the size of the bite mark belonged to a toddler rather than an adult. The bite mark evidence was thus used to discredit the accused’s account.

Nevertheless, compared to bite mark evidence, fingerprint evidence is widely regarded to be a reliable form of pattern recognition evidence. In fact, “Fingerprints have become the accepted standard for identification by the government, banks, and even handphones.” Since fingerprints are individualistic, it would also be simpler to do a statistical analysis compared to bite mark evidence.

Forensics in Singapore and the United States of America

We also took this opportunity to ask Mr Lee about his experience in the US, where he studied forensic science under Dr Henry Lee, a renowned Taiwanese-American forensic scientist. Mr Lee identified two key differences between the practice of forensic science in Singapore and the US.

Firstly, it is relatively easy for the defence to obtain forensic experts in the US. In Singapore, however, forensic experts from HSA largely work with the prosecution and the police. The defence has access to a smaller pool of forensic experts and they may even need to engage forensic experts from overseas.

Secondly, “Prosecution expert evidence is constantly being challenged in the US, ” remarks Mr Lee. US attorneys tend to attack not just the forensic reports, but the expert witnesses themselves. There are even courses organised by defence lawyers on how to tackle forensic experts, starting with the report, then quickly moving on to the “witnesses’ history, work and love life”. The situation is such that more forensic experts in the state and federal courts are afraid of being sued. Although such a phenomenon is not currently present in Singapore courts, Mr Lee cautions that this practice might be gradually adopted here.

Future of forensic science

How will the use of forensic science in Singapore continue to develop? Mr Lee believes it will become more commonplace as prosecutors increasingly rely on forensic science to prove that their “evidence is objective and reliable as possible”.

“Of course, we have to go with the times,” Ms Lim adds, explaining that with the increasing expectation to use forensic evidence in court, the onus is on the prosecution and HSA to produce such evidence in trial.

Concluding remarks

Although both Mr Lee and Ms Lim acknowledged that their journey as prosecutors is not smooth sailing, their purposeful work is what keeps them going.

“I persevere and think that the work is very meaningful. It is something that we do, to give people a voice,” Mr Lee says. Ms Lim then adds, “The work that I do has an impact on real people, their lives, the people around them. I think it is very fulfilling when you see victims getting justice.”

As a concluding statement, both our guests shared that if you are interested in forensic science and want to deal with it on a more regular basis, the AGC is the place to be.

We would like to extend our utmost gratitude to both Mr Lee and Ms Lim for taking their time out to be part of this meaningful interview.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

Authors’ Biography

Jeslyn Tan is a Y2 student at the NUS Faculty of Law. She is currently part of the Criminal Legal Aid Scheme, helping lawyers with pro bono criminal cases. She is also a part of CJC Forensics. In her free time, she enjoys reading fiction novels.

Phoebe is a final year undergraduate with a major in life science and a minor in forensic science. To pursue her passion in forensic science, she joined the NUS Criminal Justice Club.

CJC-F Announcements, CJC-F Insights, Uncategorized

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

Authors’ Biography

CJC-F Announcements, CJC-F Insights

General Questions

Q: At our previous seminar, Mr Sunil Sudheesan said that he was grateful for TFEG. Was there a specific reason why you decided to create TFEG?

Q: Ms Lim and Dr Tay, you both co-authored the book Forensic Science-Briefs for the Legal Practitioner. What inspired you to be part of the team for this book?

Technical Questions

Q: What has been the most important skill you have learnt in forensics?

Q: Which areas of forensic expertise are the most challenging in terms of analysis and interpretation?

Q: Are there any future forensic breakthroughs to improve the current criminal justice system?

Q: Dr Tay, while you were in HSA, you were the only traffic accident reconstruction expert. How often do you have to deal with such forensic evidence?

Q: What inspired both of you to pioneer the development of bloodstain analysis for forensic reconstruction in Singapore which has gained acceptance in court and is widely used in high-profile cases?

Q: Ms Lim, you were involved in several murder cases like Wang Zhijian. Did you go about the reconstruction process for these cases any differently from each other?

Q: When do you write research papers?

Questions about the Legal Process

Q: How is a case typically allocated to you?

Q: Forensic experts keep case notes with detailed write-ups of the case. Is it common for forensic experts to refer to case notes during trials?

Q: How would you demonstrate simulation experiments in court?

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

Authors’ Biography

Nicole Teo is currently pursuing a degree in Law and in the middle of her second year of the programme. She is aspiring to be a prosecutor one day, which sparked her interest in all things related to criminal law, including forensic science.

Sheryl Seet is a final year undergraduate, majoring in Life Sciences with a Minor in Forensic Science. An aspiring forensic scientist, Sheryl hopes to contribute her wealth of knowledge in forensic science and play a vital role in the criminal justice system.

CJC-F, CJC-F Activities, CJC-F Announcements, CJC-F Events

To ring in the new year, CJC Forensics recently held its inaugural Roundtable Discussion. The aim of the Discussion was for each sub-project to share the various events and publication works undertaken, provide an opportunity for cross-project learning for our own members and to update our members on upcoming events.

The event started off with a warm welcome by our advisor, Associate Professor Stella Tan. We are extremely grateful to have Prof Stella with us on the New Year’s Saturday morning!

Initiation sharing

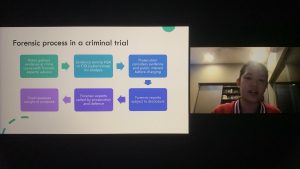

After Professor Stella Tan gave her opening address, Nicole Teo of the Initiation project kickstarted the sharing sessions. Nicole gave a brief overview of the forensic process in a criminal trial before detailing three important areas of forensics: (1) DNA; (2) fingerprinting; and (3) blood spatter.

Over the last few months, Initiation conducted interviews with various legal counsel and forensics experts such as Professor Eugene Lee, Ms Lim Chin Chin, and Mr Sunil Sudheesan. After her presentation, each member of Initiation was invited to share their takeaways from the interview. Indeed, one of the more important takeaways is perhaps how each member of a particular field shares different opinions on the same issue; it is thus important to canvass all opinions so as to obtain a broad picture without being biased.

Following the sharing by Initiation, members were then split into breakout rooms to attend the sharings by the Forensic Psychology and Drugs projects.

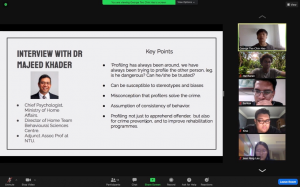

Forensic Psychology sharing

Headed by George Teo (Year 3 Psychology), members were introduced to the three main types of forensic psychology, namely forensic investigative psychology, legal courtroom psychology and forensic clinical psychology. Having conducted interviews with Dr Majeed Khader (Chief Psychologist, MHA) and Dr Julia Lam (Consultant Forensic Psychologist and founder of Forensic Psych Services), George shared some of the key takeaways, such as the importance of DNA profiling in apprehending offenders and improving rehabilitation programmes. George further outlined the four main approaches when it comes to DNA profiling: (1) the CLIP approach; (2) FBI approach; (3) investigative approach; and (4) clinical approach. It is noteworthy that the CLIP approach was pioneered by Dr Khader himself!

Members were introduced to the use of forensic psychology in almost every step of the trial process, from pre-trial assessment to witness examination and finally, in sentencing considerations. However, the presentation was not merely one-sided; there were various activities that were designed to engage all participants. One such activity was the DNA profiling activity, where members were given nine different scenarios and asked to match the scenarios that were related! On the whole, forensic psychology is an integral part of the criminal legal process and its significance should not be underestimated.

Drugs sharing

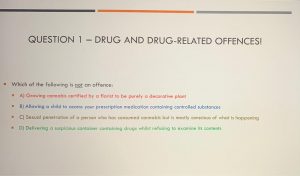

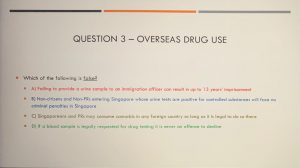

The drugs sharing was covered by Mitchell Leon (Year 4 Law). Mitchell began by sharing about several drug laws, including consumption (s 8(a) Misuse of Drugs Act (“MDA”) and possession (s 8(b) MDA). He also explained the difference between trafficking (s 5 MDA) and importation (s 7 MDA). Put simply, trafficking refers to the local supply of drugs while importation refers to foreign supply of drugs entering Singapore.

Following a short Kahoot! quiz, Mitchell delved into the history of drug laws and explained how it could have formed the basis of the divide between the Western liberal view and the more conservative Asian view. Indeed, while the Westerners did not experience the full ill effects of extensive drug use, Asians were subject to more suffering and poverty as a result of drug consumption.

Finally, Mitchell shared that the UN has recently re-classified cannabis as a less harmful drug under the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. While Law Minister K Shanmugam has claimed that the decision was fueled by studies conducted by profit-driven companies, it was noted that the Minister’s view may be a reflection of the history of colonialism in Singapore, where Chinese coolies were given opium and severely underpaid. However, rather than dismissing either view too quickly, it is important to understand each view’s historical, economic, and political background, as opposed to the merely the legal and scientific implications of drug use.

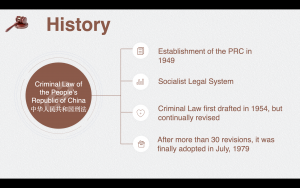

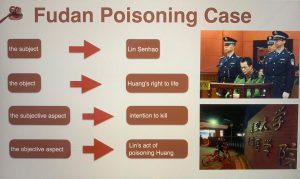

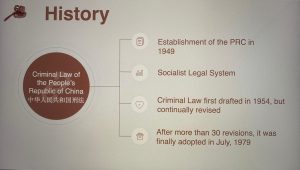

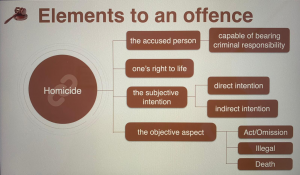

Introduction to Chinese criminal law

Following the sharing by the various projects, the members reconvened for an introduction to Chinese criminal law. The sharing was conducted by Wu Yue, a law graduate from China who is currently pursuing a Masters in NUS Forensic Science Programme. It was our privilege to invite her to introduce the Chinese criminal law to our members. We were introduced to the aims of the criminal justice system, the court system, the elements of an offence, and the use of forensic science in Chinese criminal law.

China has its own equivalent of Singapore’s Penal Code (“PC”), the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China (loosely referred to during the presentation as the China Criminal Code (“CCC”)). There are two main aims of the criminal justice system: (1) punishing the wrongdoer; and (2) protecting society. Wu Yue further brought members through the three key principles underpinning the criminal justice system, namely, legality, equality and suitability.

The structure of the court system in China bears the same vertical hierarchy as that of the Singapore courts, with the Supreme People’s Court serving as China’s apex court. As outlined by Wu Yue, the Supreme People’s Court has three main functions:

- adjudication;

- a quasi-legislative function in enacting judicial interpretations; and

- issuing guidance cases.

Unlike precedents in common law jurisdictions, the guiding cases issued by the Supreme People’s Court should only be referred to when the people’s courts are adjudicating similar cases. They serve as a aid to judicial reasoning rather than a binding precedent.

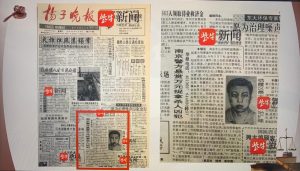

In emphasizing the importance of forensic science in China’s criminal justice system, Wu Yue cited the Nanjing 1-19 Incident, where Lin, a student was found bludgeoned to death. Twenty-eight years on, DNA evidence was used to confirm a suspect’s identity and catch the killer.

Ultimately, the importance of forensic science is not just limited to Singapore; it has a crucial role to play in all jurisdictions, and each country must do its part to facilitate the growth of this crucial field.

Winter Townhall

Having completed the various sharings, members were updated on some of the projects that they can look forward to in the coming semester, including a cyber forensics project, a forensic psychology seminar, and of course, the all-important Forensic Science Conference! (sign up here – http://tinyurl.comCJCFS2021 !).

Members were also given a glimpse of a video done by Lee Jia Ying, Lau Jean Ning and Mohamed Sarhan; the video provides a case study on PP v Teo Heng Chye, where the defence of intoxication was accepted in reducing the conviction from one of murder to culpable homicide not amounting to murder. Keep a look out for the video, which will be released later this week!

Conclusion

After a grueling first semester, the CJC-F Roundtable Discussion provided a much-needed opportunity for members to bond and share the various takeaways from their projects. At the same time, it provided a glimpse of the exciting events and projects we have lined up for the coming semester!

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

Author’s Biography

Hariharan Ganesan is a Y2 student at the NUS Faculty of Law. He is currently pursuing his interest in criminal law working as a research assistant for Assistant Professor Cheah Wui Ling. He is currently a Project Manager in CJC Forensics, heading the publication Initiations: A Glimpse into Forensics. Beyond school, Hariharan volunteers as a Silver Generation Ambassador, reaching out to Merdeka Generation seniors on the Merdeka Generation Package. In his free time, Hariharan enjoys playing squash recreationally.

Hariharan Ganesan is a Y2 student at the NUS Faculty of Law. He is currently pursuing his interest in criminal law working as a research assistant for Assistant Professor Cheah Wui Ling. He is currently a Project Manager in CJC Forensics, heading the publication Initiations: A Glimpse into Forensics. Beyond school, Hariharan volunteers as a Silver Generation Ambassador, reaching out to Merdeka Generation seniors on the Merdeka Generation Package. In his free time, Hariharan enjoys playing squash recreationally.

Nicole Teo is currently pursuing a degree in Law and in the middle of her second year of the programme. She is aspiring to be a prosecutor one day, which sparked her interest in all things related to criminal law, including forensic science.

In light of the recent Penal Code reforms, s 300 on murder still remains virtually the same. However, over the years legal academics have raised riveting points as to how certain provisions of s 300, in particular s 300(c) and s 300(d), are in need of reform due to questions of unfairness and redundancy. This article will aim to shed some light on these arguments and hopefully give its readers a better understanding of potential inconsistencies in the Code.

S 300(c): Is it fair?

As per s 300(c), any voluntary act causing death is murder “if it is done with the intention of causing bodily injury to any person, and the bodily injury intended to be inflicted is sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death.”

The mens reas requirement can be split up into two distinct elements:

- The accused intended to cause bodily injury.

- The bodily injury intended to be inflicted is sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death.

The court in Virsa Singh v State of Punjab [1958] SCR 1495 (“Virsa Singh”) added an additional requirement of nexus between the intended injury and the injury actually inflicted which was sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death, which has been subsequently endorsed by Singapore’s courts. The court held at [1500] that there must be “an intention to inflict th[e] particular bodily injury” which caused death and that the “the injury of the type just described [must be] sufficient to cause death in the ordinary course of nature”. The court further added at [1501] that the second party of the enquiry “is purely objective and has nothing to do with the intention of the offender”.

According to the principles outlined in Virsa Singh, as long as the bodily injury inflicted which caused the victim’s death is of the same type as the intended bodily injury and the bodily injury inflicted is sufficient to cause death in the ordinary course of nature, then the accused would be guilty of murder under s 300(c) even if he only intended lesser harm and did not contemplate the possibility of death.

Such an objective approach to s 300(c) raises several issues, the first being that “punishment is thus imposed out of proportion to the degree of culpability of the offender”. As Ramraj explains, given that s 300(c) “expressly directs” the courts to consider “only whether the actual injury was sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death, it is difficult to imagine a situation in which the court would ever conclude that it was not, except on the most unusual facts”. This can lead to an outcome where “a person can be convicted of murder even if he or she intended to inflict only the most trivial of injuries if somehow the injury results in death”. In such a case, the punishment of life imprisonment or discretionary death sentence for s 300(c) seems unfairly excessive and disproportionate when compared to the accused’s established culpability.

The second issue arising from s 300(c) is that criminal liability would now depend on “moral luck”, in the sense that “it depends on luck or chance and, in any event, on circumstances that are beyond that person’s control as a moral agent”. In explaining his point on “moral luck”, Ramraj referred to the following two hypothetical scenarios:

- “X cuts the victim on his foot with the specific idea of avoiding the causing of a fatal injury. But an artery is severed and the medical evidence is that in the ordinary course of nature the injury would prove to be fatal.”

- “Y cuts the victim on his foot with the specific idea of avoiding the causing of a fatal injury. The knife misses an artery by two millimetres and the victim suffers but a minor injury.”

Assuming that neither X nor Y “has any special knowledge of human anatomy, it is purely a matter of chance that X happens to hit an artery but Y does not”. However, X and Y face “profoundly different penal consequences”, whereas “Y faces a charge of voluntarily causing hurt” and a maximum of imprisonment for three years, X faces the punishment of life imprisonment or discretionary death sentence. As Rajah put it, the fact that this difference in legal outcomes is a result of something as fickle and unpredictable as moral luck, “is manifestly unfair and inconsistent with a criminal justice system that has any concern for the moral culpability of the offender”.

S 300(d): Is it redundant?

As per s 300(d), any voluntary act causing death is murder “if the person committing the act knows that it is so imminently dangerous that it must in all probability cause death, or such bodily injury as is likely to cause death, and commits such act without any excuse for incurring the risk of causing death, or such injury as aforesaid.”

The illustration of s 300(d) provided in the Penal Code is as follows; “A, without any excuse, fires a loaded cannon into a crowd of persons and kills one of them. A is guilty of murder, although he may not have had a premeditated design to kill any particular individual.” A closer examination of this classic illustration suggests that cases intended by the Penal Code to fall under s 300(d) can actually be subsumed under s 300(a) instead, making s 300(d) somewhat redundant.

As per s 300(a), any voluntary act causing death is murder “if the act by which the death is caused is done with the intention of causing death”. Intention can be divided into direct intent and oblique intent. When first introduced in academic literature, oblique intent was defined as “a side effect that you accept as an inevitable or certain accompaniment of your direct intent”. This idea of virtual certainty of death has been accepted as a subset of intention in Woollin [1999] 1 AC 82 at [96], and a similar test was approved in Ong Beng Leong v PP [2005] 1 SLR(R) 766 at [24], in the context of the Prevention of Corruption Act. Oblique intent is now officially recognised as a definition of intention under the Penal Code in s 26C(2)(b), as of the recent Penal Code reform in 10 February 2020.

Turning back to illustration (d), when A fired a cannon into a crowd his direct intent may not have been to kill anyone. However as long as it can be proven on the facts that he was virtually certain that death would be a side-effect of firing the cannon, he is guilty of a crime under s 300(a). Thus, s 300(d) becomes redundant as cases of foreseen but not intended risks of death intended by the Code’s drafters to fall under s 300(d) can now be dealt with under s 300(a).

Conclusion

As it has been argued, the Code is not without its flaws. There is always room for improvement and we have our legal academics to thank for helping to give their input. It is our hope that future amendments to the Code will continue to strive for consistency and fairness.

Ashna Khatri

CJC-F, CJC-F Announcements

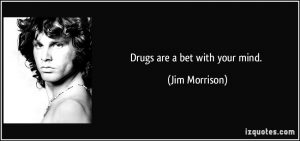

Turning to illicit drugs is like throwing a die, flipping a coin, or even picking a card – it is like gambling. American songwriter Jim Morrison once said “Drugs are a bet with your mind”. You go out for a night of fun and after a couple of pills, you might not know where you would end up the next day. It could work out well, but it could otherwise be disastrous.

Source: https://quotesgram.com/img/jim-morrison-quotes-on-drugs/367239/

The War on Drugs

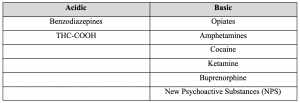

There are primarily seven classifications of drugs: Narcotic Analgesics, Hallucinogens, Central Nervous System (CNS) Depressants, CNS Stimulants, Dissociative Anaesthetics, Inhalants and Cannabis. These drugs can be categorized based on certain shared symptoms or the effects that they have. Additionally, they can be further classified according to their chemical properties, acidic and basic properties, which can be used for identification. Some of the commonly encountered controlled drugs and their properties can be seen from the table below.

Table 1: Panel of drugs tested in Health Sciences Authority (HSA) categorized by their chemical properties

Over the years, the global drug market has been expanding rapidly and becoming increasingly complex. New substances are entering the market and concurrently, laboratories need to be well-equipped with advanced analytical instrumentations to identify these new illicit drugs. Evidently, the constant evolution of laboratory-based drug testing can be seen from the introduction of urine drug testing, hair drug testing, and other upcoming potential drug testing methodologies. This includes making use of only fingerprints and oral fluids to detect excreted metabolites of drug abuse.

As established from the previous article, there are four main types of drug offences in Singapore: Possession, Consumption, Trafficking, and Importation. For the Possession, Trafficking, and Importation offences, drugs seized are analysed both qualitatively (identification of drugs) and quantitatively (quantity of drugs) in the laboratory. On the other hand, for the Consumption offences, the suspected subject would have to undergo tests like urine and hair tests to determine the quantity and types of drugs consumed. The respective penalties are then given subsequently, according to Singapore’s legal system, based on the offences committed as well as the results of the examinations.

The Different Departments

In Singapore, there are several different agencies with the expertise of drug testing – the Health Sciences Authority (HSA) and the Forensic Experts Group (TFEG) are such examples. As a government agency, the HSA possesses the resources to host both the Illicit Drugs Laboratory (IDL) as well as the Analytical Toxicology Laboratory (ATL). The IDL analyses controlled drugs from seizures and assists in clandestine drug laboratory investigations. On the other hand, the ATL analyses biological fluids and forensic exhibits for drugs and poisons. In other words, the IDL primarily focuses on seized physical drugs, whereas the ATL focuses on the consumed drugs. Other than these two laboratories, there are also other forensic labs in the HSA working closely together with them.

For example, the HSA Forensic Medicine Division and the ATL work hand in hand to determine if there are any drugs or poisons which could have contributed to the victim’s death. Such collaborations support the law enforcement agencies as well as health institutions like hospitals and medical clinics.

TFEG, as a non-governmental agency based in Singapore, provides expert forensic services not just locally, but in Asia, the USA and UK as well.

Source: https://www.hsa.gov.sg/ & https://lawgazette.com.sg/practice/practice-support/engaging-and-working-with-a-forensic-expert/

The Scrutinization of Mediums

At this point, one key question you might ponder would be: How exactly is the analysis of drugs done in these laboratories? There are several robust testing methods used in these laboratories for drug testing and it is crucial to dissect each of them carefully. However, before diving into the technicalities, it is also pivotal to understand the different substances obtained for analysis. For the IDL, the seized drugs are often already in a physical state ready for drug analysis. On the other hand, for the ATL, the complexity of the biological samples collected increases the difficulty of analysis.

There are primarily two types of substances entrapping drug specimens – biological and non-biological samples. Non-biological samples refer to samples from water sources, drug formulations, ambient air and more. They are usually less complex to analyse, as compared to biological samples, and are less time sensitive and abundant. In contrast, biological samples like blood, urine, and saliva samples (samples the Analytical Toxicology Laboratory focuses on) are highly complex, more time sensitive and limited. These samples are also known as mediums in which drugs can be found after consumption.

Specifically, the Drug Abuse Testing unit in the ATL analyses urine and hair specimens for the presence of controlled drugs. Since urine samples are available in considerably larger amounts, as compared to other biological samples, and hair samples allow for long-term retention of analytes, they are usually preferred for analysis.

Source:: https://www.quora.com/What-is-the-chemical-composition-of-urine & https://activilong.com/en/content/95-structure-composition-of-the-hair

The qualification and quantification analysis obtained from these mediums would then be used as evidence in court.

Analytical Instruments

Generally, there are two testing methodologies typically used by experts for drug analysis. They are Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) and Liquid Chromatography-Mass-Spectrometry (LC-MS)

GC-MS and LC-MS are the two most employed techniques by the drug testing agencies today for the qualification and quantification of drugs seized. They are heavily utilised for the detection of targeted compounds present in samples such as complex biological specimens, as well as raw materials. The objective of both GC-MS and LC-MS is to separate and analyse the target compounds of interest from the sample mixture. GC-MS is typically used for volatile samples that can be easily vaporised, whereas LC-MS is used for non-volatile samples.

The GC works on the principle that a mixture will separate into individual substances when heated. As such, the heated gases are typically carried through a column with an inert gas and emerge from the column opening as separated substances before flowing into the MS. In comparison, the LC is more ideal for molecules which might not be suitable to undergo GC-MS, also known as polar and non-volatile molecules. The samples are also usually carried out in a column (packed with different particles) and emerge from the column opening as separate compounds after interacting with them, and flowing into the MS. The MS then identifies compounds passed from the GC or LC by scrutinising the mass of the analyte molecule as an analytical detector.

Source: http://hiq.linde-gas.com/en/analytical_methods/liquid_chromatography/index.html#:~:text=Liquid%20chromatography%20(LC)%20is%20a,a%20column%20or%20a%20plane.

Furthermore, there are also other less commonly utilised analytical testing methods employed such as Raman Spectroscopy and Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy.

Raman Spectroscopy is an analysis technique that enables rapid qualitative and quantitative detection of the chemical compounds present. Through the study of vibrational transitions in molecules, the Raman Spectroscopy presented itself as a fast and non-destructive instrument for analysis of drugs in different product states.

Lastly, the Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) is also a technique commonly used to analyse compounds in solid or liquid samples. The AAS detects elements by looking at the different absorbance of wavelengths from a light source. By taking advantage of the characteristic that individual elements have different absorbance of electromagnetic radiation, the AAS has an unlimited number of applications.

The Key to Understanding

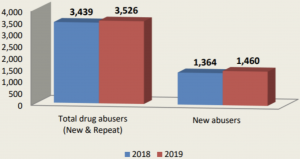

Singapore has strict laws against drug abuse. The Misuse of Drugs Act (MDA) is the main legislation for drug offences in Singapore. It provides for the enforcement powers of Central Narcotics Bureau (CNB) and the penalties for various drug offences, including trafficking, manufacturing, importation or exportation, possession, and consumption of controlled drugs. However, despite the penalties put in place, drug abuse in Singapore is still on the rise and continues to be a problem as reflected in CNB’s latest figures in 2019. The largest group of drug abusers in Singapore belong to individuals who are aged between 20 and 29, and 41% of the arrested abusers were new drug abusers.

Source: https://www.cnb.gov.sg/docs/default-source/drug-situation-report-documents/cnb-annual-statistics-2019.pdf

As such, the current drug situation in Singapore still requires intensive enforcement efforts against drugs and more efficient testing methodologies. Scientific and technological breakthroughs like the Next-Generation Reporting Centre (NGRC), which significantly improves the efficiency of urine tests, automating the printing and pasting of labels on urine specimen bottles, are required for the progress of Singapore’s current testing methods. Above all, the key to understanding the science behind drug offences would ultimately be to master the fundamental methodologies and to constantly evolve.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

References

A quote by Jim Morrison. (n.d.). Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/368668-drugs-are-a-bet-with-your-mind-it-s-like-gambling

7 Drug Categories. (n.d.). Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://www.theiacp.org/7-drug-categories

Illicit drugs. (n.d.). Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://www.hsa.gov.sg/about-us/applied-sciences/illicit-drugs

Bailey, M., Bradshaw, R., Francese, S., Salter, T., Costa, C., Ismail, M., . . . Puit, M. (2015, May 01). Rapid detection of cocaine, benzoylecgonine and methylecgonine in fingerprints using surface mass spectrometry. Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2015/an/c5an00112a

Singapore’s Drug Laws: Possession, Consumption and Trafficking. (2020, December 01). Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://singaporelegaladvice.com/law-articles/what-are-singapores-laws-on-drug-consumption/

Analytical toxicology. (n.d.). Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://www.hsa.gov.sg/about-us/applied-sciences/analytical-toxicology

Decoding poisons. (n.d.). Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://www.hsa.gov.sg/careers/articles/decoding-poisons

Forensic Science Services Experts: The Forensic Experts Group. (n.d.). Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://www.forensicexperts.com.sg/

Raman spectroscopy for the analysis of drug products and drug manufacturing processes. (2017, June 08). Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://www.europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com/article/1896/raman-spectroscopy-for-the-analysis-of-drug-products-and-drug-manufacturing-processes/

Liquid chromatography. (n.d.). Retrieved December 17, 2020, from http://hiq.linde-gas.com/en/analytical_methods/liquid_chromatography/index.html

Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS) Information. (n.d.). Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://www.thermofisher.com/sg/en/home/industrial/spectroscopy-elemental-isotope-analysis/spectroscopy-elemental-isotope-analysis-learning-center/trace-elemental-analysis-tea-information/atomic-absorption-aa-information.html

Central Narcotics Bureau (2020, June 12). News Release. Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://www.cnb.gov.sg/docs/default-source/drug-situation-report-documents/cnb-annual-statistics-2019.pdf

Wen-Yi, L. (2018, May 22). New and more efficient urine sample testing system for drug supervisees in the works. Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/new-and-more-efficient-urine-sample-testing-system-for-drug-supervisees-in-the-works

AUTHORS’ BIOGRAPHY

Leona Ang Qiao En is a Year 3 undergraduate from the Faculty of Science (NUS). She is currently pursuing a Bachelor’s (Hons) degree in Data Science and Analytics with a minor in Forensic Science. She is also one of the managers of the mini-project titled “Cyber-forensics & Cyber-security”. She has a keen interest in areas such as forensic science as well as crime scene investigations. In terms of leisure activites, Leona enjoys activities such as dancing in order to stay active.

Leona Ang Qiao En is a Year 3 undergraduate from the Faculty of Science (NUS). She is currently pursuing a Bachelor’s (Hons) degree in Data Science and Analytics with a minor in Forensic Science. She is also one of the managers of the mini-project titled “Cyber-forensics & Cyber-security”. She has a keen interest in areas such as forensic science as well as crime scene investigations. In terms of leisure activites, Leona enjoys activities such as dancing in order to stay active.

Tay Bo Wen Thomson is a Year 4 Chemistry student in NUS, pursuing a minor in forensic science. He is currently completing his Final Year Internship in the Health Sciences Authority (HSA) of Singapore, working in the Analytical Toxicology Laboratory (Drug Abuse Testing). As one of the project managers of the “Forensics in Drug Offences”, he directs the newsletter publication with his co-managers and guides the team with his scientific knowledge in drugs. Thomson also has great passion in criminology and forensic sciences, aspiring to be a police officer in the Singapore Police Force in the future.

Muhammad Khairul Fikri is a Year 3 undergraduate from the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. Khai is one of the Project Managers of “Drugs & Forensics”. He is pursuing a Major in Geography and two Minors; Forensic Science and Geographical Information Systems. He is interested in the applications of technology, particularly geospatial technologies, in forensic science and crime scene investigations.