CJC-F, CJC-F Announcements, CJC-F Digital Forensics

| In this issue: • Digital forensics and its subfields • Facts and myths about digital forensics • Legal issues in digital forensics |

BZZZ… BZZZ…

6:00 AM on a Monday morning.

Bzzz… You swipe at your bleary eyes and reach for your smartwatch to shut the alarm.

Wash up, grab a bite, pick up items as you go.

Laptop, memory cards, smartphone. Check, check, and check.

Activate your home security system and off you go.

Down the requisite number of floors, past the closed-circuit television (CCTV) at the lift lobby, and finally into the comfort of your Grab car.

Clear some emails enroute and there you are, your e-wallet relieved of the ride fare.

Through the office entrance, past even more CCTVs, and finally into the meeting room where you link your laptop to the network and exhale in relief just as your boss inhales to speak.

Snatching glances at the smart coffeemaker in a corner, you count down to the first break.

DID YOU CATCH all the digital elements? Does it surprise you how connected we are?

Millennials might call it a blurse, a mixture of ‘blessing’ and ‘curse’. Digital technology brings us together while keeping us at a distance; the growing number of functions simplify yet complicate our lives; and when a crime happens, digital data can incriminate or vindicate.

DIGITAL FORENSICS IS a field within forensic science that involves the retrieval, preservation, and analysis of electronic data to assist in investigations and court processes (NIST, n.d.). This encompasses data from digital devices (e.g. computers, hard drives, mobile phones, portable storage media, motor vehicles, drones, CCTV) as well as digital platforms (e.g. cloud, network, Internet of Things, email). Regardless of the data type, the digital forensic methods used must be accurate, reliable, scientifically valid, and protect the integrity of the original data. However, the specific methods and challenges depend on the subfield of digital forensics we are concerned with.

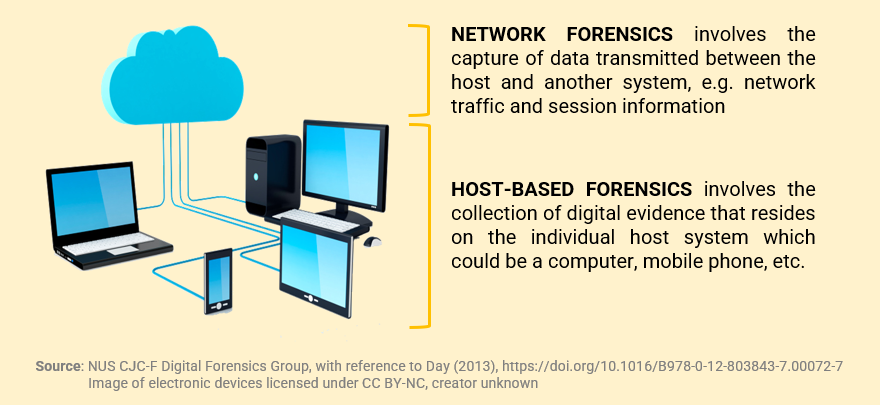

Broadly, digital forensics can be thought of as comprising two subfields:

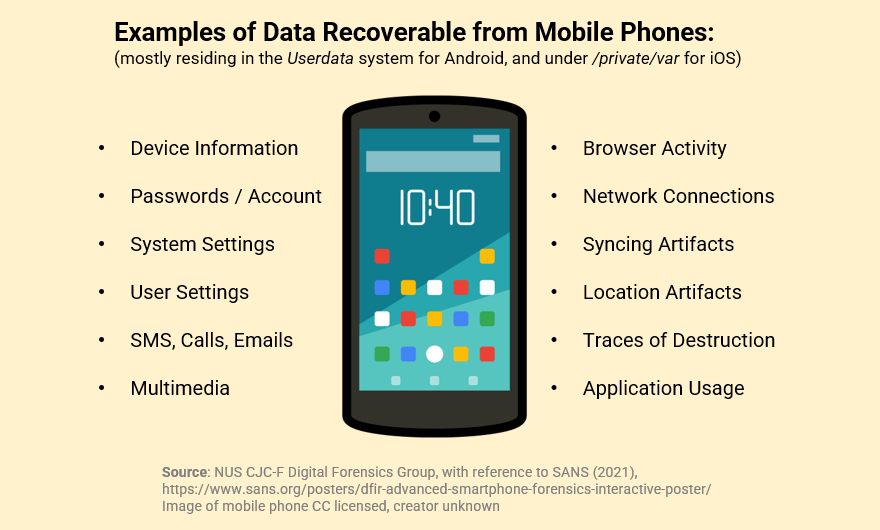

LOOK AT YOUR TRUSTY SMARTPHONE, sitting innocuously within reach or perhaps even in your hand as you are reading this. Your phone is an example of a host system. Troves of digital evidence are accumulated and transmitted with each tap you make, each message you receive. If we were to seize your phone right now, what might we find?

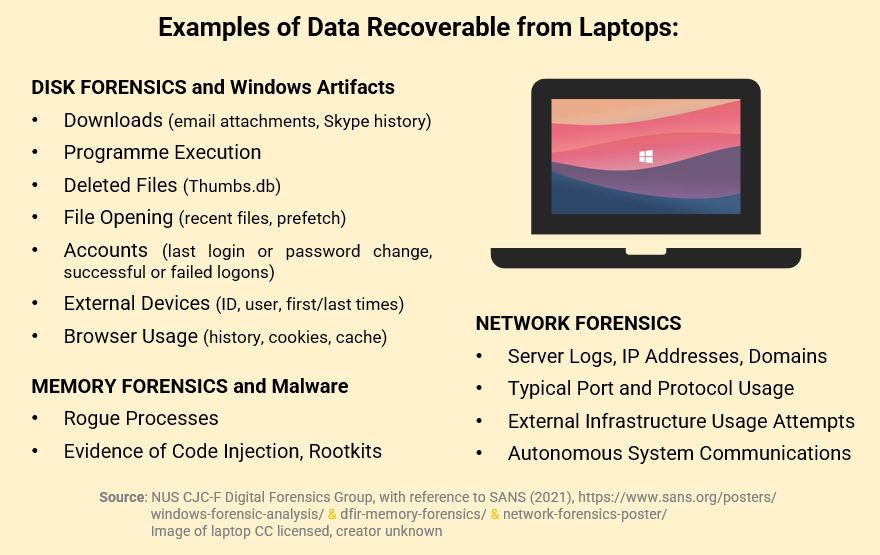

NOW, THE LAPTOP YOU BRING to school or work each day. What might we find there?

That’s a huge amount of digital evidence you’re carrying around, probably rivalled by the ton of questions circling your mind now. So, let’s correct some facts and bust some myths.

FACT OR FICTION?

| Since we have a rough idea of where to locate the pieces of digital evidence, an experienced digital forensic investigator would be able to solve a crime in a matter of keystrokes. Whoever said CSI was just drama! |

| Highlight for the answer ▼ [Start of answer] Unfortunately, this is fiction, and there are several reasons (NIST, 2006) for this: Before even getting to analysis, the investigator has some hurdles to clear, one of which is to collect the data in a way that preserves its integrity. The seized device may need shielding from external influences. This is done by placing it in a Faraday box to block any electromagnetic radiation which can alter the data on the device. If the device is running, power sources need to be established so that the device does not shut down, taking with it any traces of volatile data. These measures take time to implement, making it unlikely that an investigator can launch into code-cracking immediately in good ol’ CSI fashion. Acquiring the data may entail generating a byte-for-byte copy of the original media. Depending on the volume of data, the acquisition process could take minutes to more than a day. And the investigator has yet to examine the data, much less track down the evidence! When the data is finally acquired, the investigator begins the arduous task of sifting through the mountain of information. Which files are of interest? For those that are encrypted, what is the password? How do we detect steganography, such as messages concealed within images? Encryption and steganography are examples of anti-forensics, as they are used to thwart forensic analysis and can be very challenging to resolve. Assuming the investigator has successfully amassed critical evidence from the digital data, there is still a need to triangulate this with other sources of evidence, perhaps physical evidence like fingerprints. For example, a system log may show that a particular user had logged on to the computer. This is a good start, but other (possibly non-digital) evidence is needed to link the login activity to the person who was physically at the computer. It is a long way from the collection of the media to examination of the data, to analysis of the information, and to reporting of the evidence. The keystrokes you were thinking of – these are only one part of the picture, and it is rare that just a few keystrokes would do the trick. [End of answer] |

| That’s a lot of work, and a lot of skill. I guess you need to have a solid understanding of computer science (or the like) to be a digital forensic investigator. |

Highlight for the answer ▼ [Start of answer] Fact, a background in computer science or information security is usually a prerequisite for a digital forensics position. If you are curious, have a look on the Careers@Gov website. However, that does not mean you and I cannot learn to do digital forensic analyses. There are various open-source tools (e.g. Autopsy) that involve navigating a graphical user interface without knowledge of programming or coding. In fact, the authors of this article enjoyed using Autopsy despite having no prior experience in computer science or anything remotely similar. [End of answer] |

| So… If digital forensics is not that niche an area, then practically anybody can gather information about me whenever he/she wants. My personal privacy is at risk, and I don’t even know what digital traces I’ve left behind! |

Highlight for the answer ▼ [Start of answer] Thankfully, this is fiction. Take for example the TraceTogether app which collects data on our identity and contact details, Bluetooth proximity, and app analytics (Gov SG, 2021). You can imagine how handy this information would be. However, the data is only accessible to authorised police officers by invoking the Criminal Procedure Code, and even then, only for the purpose of criminal investigation and national security in serious offences (Singapore Statutes Online, 2020). Otherwise, any breach of the data or usage beyond COVID contact tracing is subject to sanctions under the Public Sector Governance Act (CNA, 2021). If the data is obtained by someone through illegal means, it may not be admissible in court either. So, rest assured, your personal privacy is secure. [End of answer] |

THE LEGAL ISSUES, of course, extend beyond the right to data access and are far more intricate.

On the most basic level, admissibility of digital evidence in court is subject to the same principles as physical evidence. The difference is in the medium of the evidence.

However, things get complicated as digital systems get increasingly mobile and remote. Cloud computing involves the distribution of digital infrastructure across the world, with many end users far removed from the geolocation of their data (Buyya, Vecchiola, & Selvi, 2013). There could be jurisdictional issues if specific laws apply in that location which are not exercised where the end user resides, or if there is a conflict of laws. These issues are still being ironed out. For example, a local model’s recent use of the OnlyFans online platform to post obscene content prompted the suggestion that ‘a Singaporean or a foreigner who uploaded [obscene] material overseas and subsequently enters Singapore could potentially be dealt with by the law’ (The Straits Times, 2022). Until there is greater clarity, digital forensic investigators will likely continue to grapple with such grey areas.

Even if localised in the same jurisdiction, legal challenges abound such as in the collection of network traffic. There may be privacy or security concerns about data (e.g. the passwords and email content of uninvolved persons) being unnecessarily exposed to investigators (NIST, 2006).

But just as there are legal challenges, there are also legal powers to deal with these challenges. Earlier on, we noted encryption as a form of anti-forensics. In Singapore, the law provides for police to direct a person to assist them (e.g. through provision of login details) in accessing a computer that is suspected to be involved in an arrestable offence. Failure to comply with such an order would constitute an offence under S 39(3) of the Criminal Procedure Code. Similarly, S 40(2)(c) of the Code confers power to the police to obtain decryption information from a person for the purposes of investigating an arrestable offence. Given the dynamism of digital technology, we can expect continuing evolution in the field of digital forensics and its associated laws.

NOW THAT YOU KNOW MORE about digital forensics, can you see yourself as an investigator?

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

References

- Buyya, R., Vecchiola, C., & Selvi, S. T. (2013). Chapter 11 – Advanced topics in cloud computing. In R. Buyya, C. Vecchiola, & S. T. Selvi (Eds.), Mastering cloud computing: Foundations and applications programming. Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-411454-8.00011-5

- Channel News Asia. (2021, January 4). Singapore Police Force can obtain TraceTogether data for criminal investigations: Desmond Tan. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/singapore-police-force-can-obtain-tracetogether-data-covid-19-384316

- Day, C. (2013). Chapter 72 – Intrusion prevention and detection systems. In J. R. Vacca (Ed.), Computer and information security handbook. Third edition. Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803843-7.00072-7

- Gov SG. (2021, July) TraceTogether FAQs. TraceTogether programme. Data privacy and permissions. https://support.tracetogether.gov.sg/hc/en-sg/articles/360043735693-What-data-is-collected-Are-you-able-to-see-my-personal-data-

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. (n.d.). NIST. Forensic science. Digital evidence. https://www.nist.gov/digital-evidence

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. (2006, August). Special publication 800-86. Guide to integrating forensic techniques into incident response. https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-86/final

- SANS Institute. (2021, March 25). Windows forensic analysis. https://www.sans.org/posters/windows-forensic-analysis/

- SANS Institute. (2021, April 15). Network forensics poster. https://www.sans.org/posters/network-forensics-poster/

- SANS Institute. (2021, May 25). DFIR advanced smartphone forensics interactive poster. https://www.sans.org/posters/dfir-advanced-smartphone-forensics-interactive-poster/

- SANS Institute. (2021, June 1). DFIR memory forensics. https://www.sans.org/posters/dfir-memory-forensics/

- Singapore Statutes Online. (2020, April 7). Republic of Singapore, Government Gazette, Acts Supplement. COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) Act 2020 (No. 14 of 2020). https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Acts-Supp/14-2020/

- The Straits Times. (2022, January 9). Obscenity: OnlyFans content creators based overseas could be breaching Singapore law. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/courts-crime/onlyfans-content-creators-based-overseas-could-be-breaching-singapore-laws-lawyers

Authors’ Biography

| Ng Phui Fun Sabrina is currently doing her Master’s in Forensic Science, with a prior background in psychology and education. She enjoys picking up new skills (the most recent being digital forensics), sometimes to the dismay of her family members as her curious tinkering has led to unintended outcomes such as rendering a brand-new phone unusable. Nonetheless, she keeps going… |

| Mitchell Leon Siu Kin graduated from the NUS Faculty of Law and completed a Minor in Forensic Science. He is currently a practice trainee and has embarked on his Master’s in Forensic Science at NUS. He is also the longest serving CJC member in history. Mitchell aspires to be a criminal defence lawyer and continues to further his knowledge of forensic science in preparation for the courtroom battles ahead. |

| Harvinder Kaur is currently pursuing a Master’s in Forensic Science. She previously graduated from The University of Queensland with a Bachelor’s in Science, Major in Biomedical Sciences. She volunteers as a Lead Researcher with Women Unbounded during her spare time. |

| Muhammad Khairul Fikri is a Year 4 undergraduate in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. He Majors in Geography and Double Minors in Forensic Science and Geographical Information Systems. Khai enjoys research and has completed several projects that integrate his fields of study. His focus is on finding novel applications of technology to help solve crime. He is also the Project Manager for the Virtual CSI Project. |

0