CJC-F, CJC-F Announcements, CJC-F Understanding Forensics

Are Forensics Quick Answers to Crimes?

Photo taken from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4851411

Ever wondered how CSI always seem to swiftly unravel crimes upon piecing the pieces of the puzzle neatly together? Do they reflect what really takes place in reality? Are you also curious about what happens to the exhibits and body of the victim after they are seized from the crime scene? What about DNA and fingerprints – are they always the infallible golden key to identifying the culprit(s) responsible for the crime?

The Role of Forensic Science in Court

Reconstruction of a crime scene is not an easy feat, contrary to the widespread belief promulgated by popular media. Forensic scientists carry out their investigative studies assiduously over many months, or even years, before arriving at convincing results robust enough to withstand cross-examination in the courtroom.

Encapsulated in Judge of Appeal Tay Yong Kwang’s wise words (following a series of dialogue sessions centred on quantification in forensic evidence at the Singapore Judicial College), the duty of forensic scientists “is to assist the Court in arriving at the truth” and to “ensure that the facts and science… are accurate.”

In its name, forensic science constitutes any scientific discipline employed in the service of the law. It provides a platform for deciphering physical evidence in a systemic manner for admission in both criminal and civil litigations. The primary goal of forensic science is to address the questions of “what” happened, “how” it happened, “when” it happened, “why” it happened and most crucially, “who” was responsible. Like other scientific subjects, forensic scientists develop hypotheses based on preliminary observations made, conduct experiments and revise their hypotheses with new results obtained before concluding their findings. After which, they testify in courts as expert witnesses for the prosecution or defence counsel, ultimately aiding the judge in fact-finding for the case.

Every Contact Leaves a Trace

In many criminal cases, Edmond Locard’s exchange principle of “every contact leaves a trace” forms the bedrock for investigations. It maintains that cross transfer of material occurs when a person comes into contact with an object or another person. Such contact gives rise to trace evidence, which are minuscule in nature but may play a substantial role in court cases. Examples of trace evidence include touch DNA, latent fingerprints, hair and fiber. These evidence recovered may assist the court in identifying, associating or dissociating a suspect with a criminal act by considering individual or class characteristics found on the evidence.

Mohamad Nazarie bin Halidi v PP

Facts: The two accused attacked and killed the victim using a sickle and a stick. The pair were charged with murder under s 302 read together with s 34 of the Penal Code (“the Code”).

Facts: The two accused attacked and killed the victim using a sickle and a stick. The pair were charged with murder under s 302 read together with s 34 of the Penal Code (“the Code”).

Holding and explanation: Convicting both the accused of murder, the Court first stated that there was a match between their DNA profiles and that found on the sickle and stick. This unequivocally placed both accused at the crime scene, implicating them with the beating and killing of the deceased (establishing the actus reus). Furthermore, the defensive wounds on the deceased indicated that the injuries were intentionally inflicted. Since the injuries were sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death, mens rea was established as well. In the absence of an applicable defence, the two accused were thus found guilty of murder and sentenced to death.

Ng Theng Suang v PP

Facts: The accused entered a goldsmith’s with his partner and fired several shots from his gun, injuring a Certis Cisco officer and a salesperson in the shop. The accused later hijacked a car and escaped, before later ditching the vehicle. The accused was charged under s 4 of the Arms Offences Act. The accused was also charged with committing robbery of the vehicle.

Holding and explanation: Convicting the accused, the Court reasoned that there was an unbroken chain of evidence that connected the shootings and the hijacking of the vehicle. In particular, the fact that the accused’s fingerprint matched that found on the glass pane window of the hijacked car indicated that it was the accused who had carried out the shootings at the crime scene. Since the bullets recovered from the victims were traced to the accused’s gun, the totality of evidence established the actus reus of using the weapon.

Furthermore, the fact that the accused fired into a room of people indicated that he intended to injure someone. In particular, the accused returned fire when the Certis Cisco officer drew his weapon, reinforcing his intention to injure. Therefore, the mens rea was established. Since there were no applicable defences, the accused was convicted and sentenced to death.

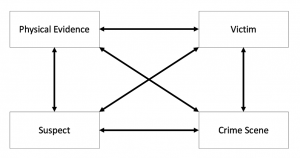

Additionally, crime scene investigators rely on the four-way linkage theory to explain the interrelations between the crime scene, physical evidence, victim and the suspect. The theory provides that if two or more components within the network can be linked, the crime may be solved. These connections may be drawn between the physical evidence recovered from the crime scene and the victim or suspect, by analysing the evidence or through verbal testimonials garnered from eyewitnesses.

Criminalistics in Singapore

Major crime scene processing techniques comprise of fingerprint pattern matching, blood splatter analysis and forensic genetics, and they often serve as useful tools in establishing the elements of a crime. Forensic medicine, on the other hand, deals with medico-legal issues. Focused branches in forensic medicine such as forensic pathology involves determining the time and cause of death by examining wounds and injuries on the victim’s body, while forensic toxicology investigates the effects of poisons and xenobiotics on the human body. Forensic psychology and psychiatry help elucidate the state of mind of an individual by eliciting visceral evidence through psychological assessments.

In Singapore, the Health Sciences Authority (HSA) serves as the primary authority providing criminalistics services for the court. The DNA Profiling and DNA Database laboratories offer genetic testing services to law enforcement agencies and generate DNA profiles for identification of persons and kinship analysis. The Forensic Chemistry and Physics Laboratory is responsible for examination of various crime scene evidence ranging from trace evidence and questioned documents to bloodstains and toolmarks. The Illicit Drugs Laboratory carries out quantitative and qualitative analyses for the presence of illicit substances in seized items. Last but not least, the Analytical Toxicology Laboratory tests for drugs of abuse and poisons in biological fluids such as blood and urine, which would serve as relevant evidence in prosecuting cases.

Drawing from multiple disciplines, forensic science aids investigation and evaluates credibility of testimonies, establishes elements of an offence, and in so doing aids the judge in reaching a just decision.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

References

- Andrew R. W. Jackson & Julie M. Jackson. 2017. Forensic Science, 4th Pearson.

- Health Sciences Authority. Retrieved July 31, 2020, from https://www.hsa.gov.sg/

Authors’ Biography

Associate Professor Stella Tan has postgraduate qualifications in law and science from NUS, and a postgraduate forensic science qualification from the Henry C. Lee Institute of Criminal Justice and Forensic Science, where she graduated top of her class under the tutelage of Dr Henry Lee, a renowned forensic expert in the United States of America. Prior to joining NUS in 2018 as a full-time faculty member, she was a Deputy Senior State Counsel at the Attorney-General’s Chambers where she was the lead prosecutor for a wide range of cases, including murder, sexual assault and drugs, and later Director (Prosecution and Legal Policy) at the Health Sciences Authority (HSA), where she provided legal advice and practical training to forensic experts. Prof Stella Tan is currently the Director of the Forensic Science undergraduate and postgraduate programmes at the Faculty of Science. She runs modules in both the Faculty of Law and the Faculty of Science. The modules which Prof Tan teaches are as follows: LSM1306 Forensic Science, SP3202 Evidence in Forensic Science, SP4261 Articulating Probability and Statistics in Court, SP4262 Forensic Human Identification, SP4263 Forensic Toxicology and Poisons, SP4264 Criminalistics: Evidence and Proof, SP4265 Criminalistics: Forgery Expose with Forensic Science, SP4266 Forensic Entomology, FSC5199 Research Project in Forensic Science, FSC5101 Survey of Forensic Science, FSC5201 Advanced CSI Techniques, FSC5202 Forensic Defense Science, FSC5203 Digital Forensic Investigation, FSC5204 Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, FSC5205 Forensic Science in Major Cases and LL4362V/FSC4206 Advanced Criminal Litigation – Forensics On Trial. Prof Stella Tan is also the Principal Investigator of the NUS Forensic Science Laboratory, where her collaborators include the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Singapore Police Force and Central Narcotics Bureau. Her interest in nurturing students has won her Dean’s Meritorious Teaching Awards as well as the Best Supervisor award for Undergraduate Research Opportunities.

Associate Professor Stella Tan has postgraduate qualifications in law and science from NUS, and a postgraduate forensic science qualification from the Henry C. Lee Institute of Criminal Justice and Forensic Science, where she graduated top of her class under the tutelage of Dr Henry Lee, a renowned forensic expert in the United States of America. Prior to joining NUS in 2018 as a full-time faculty member, she was a Deputy Senior State Counsel at the Attorney-General’s Chambers where she was the lead prosecutor for a wide range of cases, including murder, sexual assault and drugs, and later Director (Prosecution and Legal Policy) at the Health Sciences Authority (HSA), where she provided legal advice and practical training to forensic experts. Prof Stella Tan is currently the Director of the Forensic Science undergraduate and postgraduate programmes at the Faculty of Science. She runs modules in both the Faculty of Law and the Faculty of Science. The modules which Prof Tan teaches are as follows: LSM1306 Forensic Science, SP3202 Evidence in Forensic Science, SP4261 Articulating Probability and Statistics in Court, SP4262 Forensic Human Identification, SP4263 Forensic Toxicology and Poisons, SP4264 Criminalistics: Evidence and Proof, SP4265 Criminalistics: Forgery Expose with Forensic Science, SP4266 Forensic Entomology, FSC5199 Research Project in Forensic Science, FSC5101 Survey of Forensic Science, FSC5201 Advanced CSI Techniques, FSC5202 Forensic Defense Science, FSC5203 Digital Forensic Investigation, FSC5204 Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, FSC5205 Forensic Science in Major Cases and LL4362V/FSC4206 Advanced Criminal Litigation – Forensics On Trial. Prof Stella Tan is also the Principal Investigator of the NUS Forensic Science Laboratory, where her collaborators include the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Singapore Police Force and Central Narcotics Bureau. Her interest in nurturing students has won her Dean’s Meritorious Teaching Awards as well as the Best Supervisor award for Undergraduate Research Opportunities. Zheng Yen Phua is a teaching assistant for the Forensic Science programmes at the Faculty of Science. He holds an honours degree in science from NUS and is currently a doctoral researcher. The modules which he is actively involved in teaching are: LSM1306 Forensic Science, SP3202 Evidence in Forensic Science, SP4261 Articulating Probability and Statistics in Court, SP4262 Forensic Human Identification, SP4263 Forensic Toxicology and Poisons, SP4264 Criminalistics: Evidence and Proof, SP4265 Criminalistics: Forgery Expose with Forensic Science, SP4266 Forensic Entomology and LL4362V/FSC4206 Advanced Criminal Litigation – Forensics On Trial. He also received Honourable Mention as Expert Witness for the NUS Forensic Science Expert Advocacy Cup 2020.

Zheng Yen Phua is a teaching assistant for the Forensic Science programmes at the Faculty of Science. He holds an honours degree in science from NUS and is currently a doctoral researcher. The modules which he is actively involved in teaching are: LSM1306 Forensic Science, SP3202 Evidence in Forensic Science, SP4261 Articulating Probability and Statistics in Court, SP4262 Forensic Human Identification, SP4263 Forensic Toxicology and Poisons, SP4264 Criminalistics: Evidence and Proof, SP4265 Criminalistics: Forgery Expose with Forensic Science, SP4266 Forensic Entomology and LL4362V/FSC4206 Advanced Criminal Litigation – Forensics On Trial. He also received Honourable Mention as Expert Witness for the NUS Forensic Science Expert Advocacy Cup 2020. Hariharan Ganesan is a Y2 student at the NUS Faculty of Law. He is currently pursuing his interest in criminal law working as a research assistant for Assistant Professor Cheah Wui Ling. He is currently a Project Manager in CJC Forensics, heading the publication Initiations: A Glimpse into Forensics. Beyond school, Hariharan volunteers as a Silver Generation Ambassador, reaching out to Merdeka Generation seniors on the Merdeka Generation Package. In his free time, Hariharan enjoys playing squash recreationally.

Hariharan Ganesan is a Y2 student at the NUS Faculty of Law. He is currently pursuing his interest in criminal law working as a research assistant for Assistant Professor Cheah Wui Ling. He is currently a Project Manager in CJC Forensics, heading the publication Initiations: A Glimpse into Forensics. Beyond school, Hariharan volunteers as a Silver Generation Ambassador, reaching out to Merdeka Generation seniors on the Merdeka Generation Package. In his free time, Hariharan enjoys playing squash recreationally.