CJC-F Announcements, CJC-F Insights, CJC-F Understanding Forensics, CLD Forensics, Uncategorized

Doping, which refers to the illegal use of substances to enhance sporting performance, is a perennial concern in competitive sports. Interestingly, Singapore has had a number of doping cases over the years. For instance, in 2012, seven out of eight athletes tested positive for having consumed prohibited substances during the Singapore National Bodybuilding and Physique Sports Championship.

There are various substances that are abused by sportsmen, with some being more commonly used than others. To this end, the World Anti-Doping Agency (“WADA”) has promulgated the 2022 WADA Prohibited List, which contains ten categories of banned substances which may (1) be prohibited in-competition or at all times, and (2) be specified or unspecified.

This article will elaborate on four types of commonly abused substances in sports, namely:

- anabolic steroids;

- supplements;

- erythropoietins (“EPO”);

- high growth hormone (“HGH”).

1) Anabolic steroids

Anabolic steroids and diuretics are the most commonly abused substances. So what exactly are they, and why do athletes consume them?

Anabolic steroids are a special type of steroid that stimulates muscle growth, and they are typically consumed by athletes who need to quickly build muscle or speed up recovery from injuries. Examples of athletes who have been known to consume such steroids are professional body-builders and weightlifters.

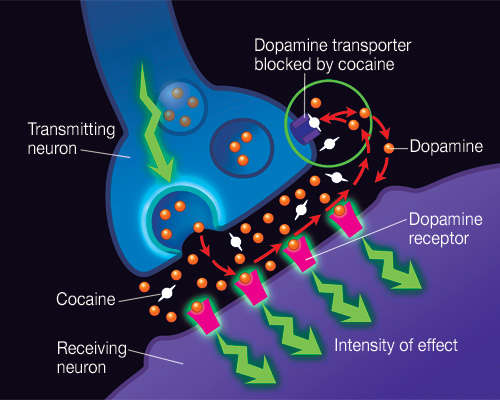

Anabolic steroids imitate the properties of naturally occurring hormones such as testosterone, given their similar chemical composition. This means that the steroid can activate the body’s testosterone receptors to induce similar or even stronger effects brought about by natural testosterone. One of the key effects testosterone has is to increase muscle mass and boost energy, making this substance an attractive one for athletes who need to build bodies faster in preparation for competitions.

While one of the key reasons behind prohibiting the consumption of these substances is to ensure a level playing field for everyone in competitions, it is also imperative to understand the potential harm that consumption can bring to athletes. Regular consumption of anabolic steroids has been known to increase the risk of hypertension, hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia amongst the athletes who imbibe them. Athletes may also suffer from acne, alopecia and even blood clots which increases stroke risk.

High testosterone levels, on the other hand, are linked to psychiatric complications like psychosis and mood disorders. This explains why doctors avoid prescribing steroids when a patient has psychiatric symptoms as the patient may develop even more severe conditions. One such condition is systemic lupus erythematosus, which is a disease that causes the immune system to attack the body’s tissues and results in tissue damage in the patient’s body.

2) Supplements

Some supplements are considered as prohibited substances under the 2022 WADA Prohibited List. The term “supplements” covers a broad category of products, including but not limited to sports foods (protein powders/drinks, energy bars, sports drinks, etc), medical supplements (vitamins, probiotics, minerals, etc), ergogenic substances (caffeine, creatinine, bicarbonate, beta-analine or nitrate), natural products (herbs, roots, etc), weight loss supplements and anabolic supplements.

Dietary supplements may also be prohibited substances – these include stimulants such as ephedrine, methylhexanamine, sibutramine (an appetite suppressant that was banned in Singapore since 2010 due to its effect of increasing risks of heart attacks) and 1,3-dimethylamylamine (DMAA). Some of these supplements may also contain other prohibited substances such as anabolic steroids and clenbuterol (a beta-2 agonist approved for asthma in some countries which also has anabolic and fat-burning properties at higher doses).

What is especially tricky about this particular class of prohibited substances is that athletes often consume these supplements not knowing that it is prohibited. In a report on elite university-level athletes, it was found that one third of the athletes had little to no knowledge of the supplement(s) that they were taking. Common reasons cited included the assumption of safety due to the wide availability of the supplements, as well as trust in the people who introduced such supplements to them (such as family members or their coaches).

This was unfortunately what happened in a case involving a local para-athlete. Khairi Bin Ishak was tested positive for methandienone (an anabolic steroid) during a routine out-of-competition test. According to him, he had purchased a protein isolate product from a Facebook page of a Malaysia-based company, not knowing that it contained substances which were prohibited. However, his lack of knowledge is not a defence for having violated an anti-doping rule. This is because anti-doping rules are strict liability in nature, and they apply regardless of whether the doping occurred intentionally or unintentionally – as long as someone is found with prohibited substances and/or at least one prohibited substance is found in a supplement, it is a violation. Consequently, the positive result of methandienone alone led to Khairi Bin Ishak being disqualified from the 2018 Commonwealth Games.

This case serves as a cautionary tale for athletes to be aware of the ingredients contained in their supplements. Manufacturers’ assurances may not be reliable, and athletes should always check their supplements with qualified professionals to ensure that they do not contain prohibited substances. Inadvertent doping can happen, so always err on the side of caution!

3) Erythropoietins

The third most commonly abused substance used by athletes is erythropoietins. EPOs are erythropoietin receptor agonists, which include darbepoetin and other EPO mimetic agents. EPOs allow more oxygen to be transported to muscle cells, thus helping athletes increase their endurance in competitive sports.

Synthetic EPO substances have structures that are different from natural EPOs produced in the body. Nevertheless, like endogenous EPO, they stimulate the production of red blood cells (“RBC”) in the bone marrow by stimulating erythroid progenitor cells, which in turn increases erythropoiesis (the production of RBCs) and ultimately regulates the concentration of RBC and haemoglobin in the blood through a negative feedback cycle. RBCs are responsible for the transport of oxygen throughout the body, so having a higher RBC count is useful as it can increase the athletes’ stamina. EPO also helps to maintain the RBCs and protects them from injury or being destroyed.

However, abuse of EPO will have a negative effect on the body. Short-term effects include weight loss, insomnia, and headaches or dizziness, but there are long-term effects as well. This is because EPO increases RBC count, such that long-term use in healthy adults can increase the risk of stroke, heart attacks and blood clots in the lungs. In addition, EPO abuse may also increase blood pressure which may damage organs such as the heart and kidneys.

The use of EPO by athletes is less common in Asian countries and is largely used only in endurance bearing sports such as cycling. The most well-known case of EPO doping is that of Lance Armstrong, who won six Tour De France competitions before being stripped of all his titles in 2012, after he admitted to using EPO to boost his performance. Interestingly, Lance Armstrong had never failed a single doping test in his entire career which led many to think that the anti-doping efforts by the International Olympic Committee are easily manipulated.

4) Human Growth Hormone

Human growth hormone, as its name suggests, is a growth hormone that is associated with growth function. HGH is a peptide (small protein) hormone naturally produced by the pituitary gland, and is involved in many crucial physiological processes such as stimulating growth of bone and collagen, facilitating turnover of muscle and regulating fat and carbohydrate metabolism.

It is not difficult to see how useful synthetic HGH can be when applied to treat growth disorders and deficiency-state diseases such as Turner syndrome, chronic renal insufficiency and short stature homeobox-containing gene (SHOX) deficiency. HGH is also highly efficient in increasing muscle mass and power and regulating metabolic (fat and carbohydrate) processes. In the context of doping, HGH is particularly attractive because of its efficiency, the absence of severe side effects if well-dosed and difficulty of detection.

However, if not well-dosed, HGH may cause severe conditions such as nerve damage, swelling and high cholesterol levels. Diabetes and tumour risks also increase with HGH usage. Further, as HGH is administered via injection so as to prevent degradation by the gastrointestinal tract, there is a risk of cross-infection if syringes are non-sterile or contaminated, leading to conditions such as HIV/AIDS and hepatitis.

What is interesting about HGH is the difficulty of detecting the substance. This is because these growth hormones typically have a very short half-life in blood and low concentration in urine. Furthermore, since synthetic HGH is nearly identical to HGH produced naturally by the human body, it is also difficult to differentiate the two. Successful detection of HGH can be achieved through blood tests.

Like EPO, this substance is not commonly abused in Singapore or Asian countries. It is more commonly found to be abused in Western countries, where endurance sports such as cycling and running are more popular and prominent.

Conclusion

It is hoped that this article has helped to shed some light on the four most commonly abused substances in sports.

Elite level athletes must always keep in mind that doping is a strict liability offence, which means that ignorance cannot be pleaded as a defence should their sample be found with a banned substance. Thus, athletes should always stay informed about the list of banned or prohibited substances to ensure that they have not unwittingly breached the WADA Code, so as to prevent any unfortunate accidents which may lead to possible sanctions.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

References

Fredrik Lauritzen (2022). Dietary Supplements as a Major Cause of Anti-doping Rule Violations. Front. Sports Act. Living, Sec. Anti-doping Sciences https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.868228

Sport Singapore. Supplements. Government of Singapore. Last accessed on 25 October 2022 from: https://www.sportsingapore.gov.sg/athletes-coaches/anti-doping-singapore/substances/supplements

Geyer, H., Mareck-Engelke, U., Reinhart, U., Thevis, M., and Schänzer, W. (2000). Positive doping cases with norandrosterone after application of contaminated nutritional supplements. Dtsch. Z. Sportmed. 51, 378–382.

Martínez-Sanz JM, Sospedra I, Ortiz CM, Baladía E, Gil-Izquierdo A, Ortiz-Moncada R. Intended or Unintended Doping? A Review of the Presence of Doping Substances in Dietary Supplements Used in Sports. Nutrients. 2017 Oct 4;9(10):1093. doi: 10.3390/nu9101093. PMID: 28976928; PMCID: PMC5691710.

Prather ID, Brown DE, North P, Wilson JR. Clenbuterol: a substitute for anabolic steroids? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995 Aug;27(8):1118-21. PMID: 7476054.

Kozhuharov VR, Ivanov K, Ivanova S. Dietary Supplements as Source of Unintentional Doping. Biomed Res Int. 2022 Apr 22;2022:8387271. doi: 10.1155/2022/8387271. PMID: 35496041; PMCID: PMC9054437. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9054437/

Health Direct. Human growth hormone. Government of Australia. Last accessed on 25 October 2022 from: https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/amp/article/human-growth-hormone

Saugy M et al (2006). Human growth hormone doping in sport. Br J Sports Med, 40(Suppl 1): i35–i39. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.027573

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2657499/

National Institute of Drug Abuse (February 2018). Steroids and Other Appearance and Performance Enhancing Drugs (APEDs) Research Report. Last accessed on 25 October 2022 from: https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/anabolic-steroids

NHS (13 April 2022). Anabolic Steroid Misuse: Instroduction. Last accessed on 25 October 2022 from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/anabolic-steroid-misuse/

National Institute of Drug Abuse (February 2018). Steroids and Other Appearance and Performance Enhancing Drugs (APEDs) Research Report

How are anabolic steroids used? Last accessed on 25 October 2022 from: https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/steroids-other-appearance-performance-enhancing-drugs-apeds/how-are-anabolic-steroids-used

World Anti-Doping Agency. World Anti-Doping Code: International Standard Prohibited List 2021. Last accessed on 25 October 2022 from: https://ita.sport/uploads/2021/10/2022_Prohibited-List_final_en.pdf

Suresh S, Rajvanshi PK, and Noguchi CT (2020). The Many Facets of Erythropoietin Physiologic and Metabolic Response. Front. Physiol., Sec. Red Blood Cell Physiology.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.01534

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2019.01534/full

Kien Vinh Trinh, Dion Diep, Kevin Jia Qi Chen, Le Huang, and Oleksiy Gulenko (2020). Effect of erythropoietin on athletic performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2020; 6(1): e000716. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000716

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7213874/

Slater G, Tan B, Teh KC. Dietary supplementation practices of Singaporean athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2003 Sep;13(3):320-32. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.13.3.320. PMID: 14669932. https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/ijsnem/13/3/article-p320.xml

Tian HH, Ong WS, Tan CL (2009). Nutritional supplement use among

university athletes in Singapore. Singapore Medical Journal, 50(2):165-172. http://www.smj.org.sg/sites/default/files/5002/5002a8.pdf

Authors’ Biographies

Javan Seow is a 4th Year Undergraduate at the National University of Singapore. He is also currently doing his final year project with the NUS Forensic Science Laboratory. He aspires to join the Singapore Police Force after he graduates.

Celine Cheow is a recent graduate from NUS Pharmacy. As a project manager of the forensic toxicology team in CJC-F in AY21/22, she guides the team with her knowledge of drugs, and edits articles relating to forensic toxicology.

Celine Cheow is a recent graduate from NUS Pharmacy. As a project manager of the forensic toxicology team in CJC-F in AY21/22, she guides the team with her knowledge of drugs, and edits articles relating to forensic toxicology.  Wong Wai Xin is a 3rd Year Undergraduate from NUS Chemistry. She is interested in practical applications of Chemistry in everyday life, and aspires to join the Ministry of Education as a teacher after graduation.

Wong Wai Xin is a 3rd Year Undergraduate from NUS Chemistry. She is interested in practical applications of Chemistry in everyday life, and aspires to join the Ministry of Education as a teacher after graduation.

Avanti Balaji (Year 2 Psychology Major)

Avanti Balaji (Year 2 Psychology Major)

Wahab (“Zee”) is a Sophomore at the SUSS School of Law and also serves as a Doping Control Officer with Anti-Doping Singapore. He looks forward to practising Community Law (Criminal, Family and Sports Law) when called to the Bar. Concurrently, serves as President of the Asian Law Students Association S’pore (ALSA SG) and strives for greater interaction and collaboration between students from the 3 Law Schools in Singapore. This is his first published article.

Wahab (“Zee”) is a Sophomore at the SUSS School of Law and also serves as a Doping Control Officer with Anti-Doping Singapore. He looks forward to practising Community Law (Criminal, Family and Sports Law) when called to the Bar. Concurrently, serves as President of the Asian Law Students Association S’pore (ALSA SG) and strives for greater interaction and collaboration between students from the 3 Law Schools in Singapore. This is his first published article. Alyssa Phua is a fourth year NUS undergraduate pursuing her double degree in Law and Business. As a strong believer in the need to promote greater appreciation of forensic evidence, she founded CJC Forensics (CJC-F) in 2020. As the director of CJC-F, she directs, coordinates and oversees all activities, events and projects.

Alyssa Phua is a fourth year NUS undergraduate pursuing her double degree in Law and Business. As a strong believer in the need to promote greater appreciation of forensic evidence, she founded CJC Forensics (CJC-F) in 2020. As the director of CJC-F, she directs, coordinates and oversees all activities, events and projects.

Nicole Teo is currently pursuing a degree in Law and in the middle of her second year of the programme. She is aspiring to be a prosecutor one day, which sparked her interest in all things related to criminal law, including forensic science.

Nicole Teo is currently pursuing a degree in Law and in the middle of her second year of the programme. She is aspiring to be a prosecutor one day, which sparked her interest in all things related to criminal law, including forensic science.