CJC-F, CJC-F Announcements, CJC-F Forensic Toxicology

Cocaine’s relationship with Violent Crimes

Introduction

Can drugs like cocaine make one turn violent after consumption? In September last year, a man (Andrew Ng Chuan Hock) was sentenced to 5 years’ imprisonment after he assaulted his elderly aunt and swung a chopper at a healthcare assistant who came to check on his aunt. Investigations revealed that the man had likely consumed drugs at the time of the offence and the psychiatrist who examined him found him to be in a state of drug-induced psychosis at the time of the crime.

This case is one of many across the world where substance abuse has been at the heart of violent crimes. In this article, we take a closer look at how and why cocaine in particular seems to encourage and perpetuate violent crime.

Goldstein suggests three main reasons for how cocaine perpetuates violence – (1) systemic violence relating to drug distribution, (2) psychopharmacologically driven crime (a.k.a. drug-induced violent behaviour), and (3) economically compulsive crime (i.e. for money to support drug habit). We’ll focus more on (1) and (2) in this article.

Image taken from: https://www.google.com/amp/s/theconversation.com/amp/researchers-block-cocaine-craving-and-addiction-with-a-special-skin-graft-103223

Systemic violence

Systemic violence has been found in the powder cocaine and crack distribution markets. This refers to violence perpetuated in the process of cocaine distribution, which can be seen as the black market equivalent of economic regulation (since such markets cannot rely on the legal system to enforce their agreements).

Some researchers believe that systemic violence is actually the main contributor to crack-related violent crimes. Such violence usually has one of two purposes – internally to discipline and control distributors along the hierarchy, and externally to protect selling territory for cocaine.

Psychopharmacologically driven crime

How does cocaine affect the brain in the first place?

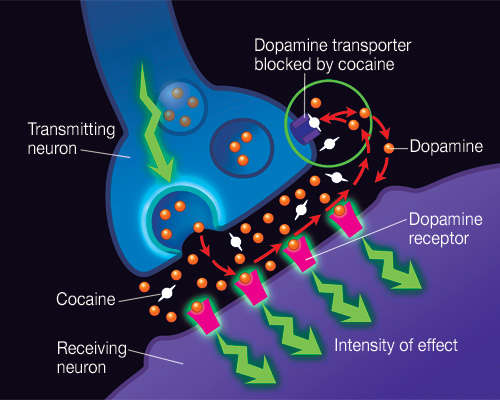

Cocaine blocks the reuptake of several neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. This creates a build-up of these neurotransmitters in the synapses (spaces between the axons and dendrites of two neurons). Of the neurotransmitters, the effects of dopamine play a particularly significant role in addiction to cocaine.

While dopamine build-up happens throughout the neurons in the brain, an area of the brain known as the nucleus accumbens (NAc) seems to be particularly affected. Stimulation by dopamine causes neurons in the NAc to produce feelings of pleasure and satisfaction, whereby the amount produced by cocaine exceeds that of those caused by natural biological functions. This causes cocaine to be so addictive as the feelings of pleasure encourage repeated usage.

Image taken from: https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/cocaine/how-does-cocaine-produce-its-effects

Additionally, cocaine also affects other areas of the brain such as the hippocampus and amygdala, otherwise known as the memory centres. These memory centres help people to remember what led to the feelings of pleasure (corresponding to the release of dopamine in the NAc). As such, when someone experiences a cocaine high, memories of the people, places, intense pleasure and other things associated with the drug-taking are imprinted in the hippocampus and amygdala. As such, returning to those places or even just encountering drug-related objects can already trigger the emotionally-loaded (and pleasurable) memories from previous cocaine uses and a desire to repeat the experience.

In addition, cocaine also damages the frontal cortex, which is the area of the brain that would normally allow the recognition of negative effects and forgo pleasurable but possibly harmful experiences if necessary. In essence, the frontal cortex is what would enable people to stop taking drugs (or not take them in the first place). However, cocaine damages the frontal cortex of which ultimately damages its inhibitory function in preventing someone from taking cocaine.

Cocaine can also affect a user’s mood even from the first use. Mood swings can result from frequent use. Since cocaine stimulates the nervous system, there are many symptoms of cocaine usage that contribute to violence – a feeling of invincibility, increased confidence, reduced inhibitions, and higher pain tolerance. Cocaine users are also prone to anxious, agitated, aggressive, and paranoid behaviour. These might be due to the effects of cocaine on the neurotransmitters dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine, all of which are relevant in psychiatric symptoms.

Cocaine effectively encourages violent behaviour, either as a result of drug use or perpetuated by the user’s own expectation of such effects.

However, psychopharmacologically driven crime may be the least important explanation for the relationship between cocaine and violent crimes. Studies have not shown cocaine use as a strong or sole cause for violent crimes as a result of psychopharmacological effects.

Legal ramifications

Around the world, countries such as Portugal had decriminalised the personal use and possession of drugs like cocaine. Singapore, nevertheless, retains a strong stance against drug use and if one is caught with possession, consumption and trafficking of cocaine, there will be major legal ramifications attached, with the most severe consequences reserved for trafficking offences.

This is because, as the High Court in Dinesh Singh Bhatia s/o Amarjeet Singh v Public Prosecutor had observed, “withdrawal symptoms [of cocaine usage] were commonplace. It could also cause psychosis in the shape of a feeling of persecution, which might have extremely dangerous consequences.” This is the reason why the High Court was of the opinion that the “usage [of cocaine] cannot be countenanced or tolerated in any measure whatsoever [as] its potency and addictive allure have caused untold misery.”

As such, the High Court took the position that the “need for deterrent sentencing in connection with cocaine-related offences is both axiomatic and compelling”, given that a “permissive culture of cocaine consumption cannot be allowed to take root in Singapore.”

Cocaine is classified as a Class A drug in Singapore. Under section 8(b) of the Misuse of Drugs Act (MDA), consumption of any controlled or specific drugs (which includes cocaine) is an offence.

The punishment for such is harsh as well. The maximum penalty for engaging in such a behaviour includes 10 years of imprisonment, or a fine of $20,000 or both. Worse, under the MDA, those convicted of trafficking more than 30 grammes of cocaine face the death penalty.

In conclusion, it is important to understand the serious legal ramifications of drug consumption in Singapore. Regardless of whether an individual is consuming the drugs and remaining within the confines of their home, or going on an assault spree, the law will not compromise its tough stance on drugs.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

References

- The Relationship between Cocaine and Violence. Life Works. Retrieved January 14, 2022, from https://www.lifeworkscommunity.com/blog/the-relationship-between-cocaine-abuse-and-violence

- United States Sentencing Commission. (1995, February). Cocaine & Federal Sentencing Policy. https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/news/congressional-testimony-and-reports/drug-topics/199502-rtc-cocaine-sentencing-policy/CHAP5-8.pdf

- Carvalho, H. B. D., & Seibel, S. D. (2009). Crack cocaine use and its relationship with violence and HIV. Clinics, 64(9). https://doi.org/10.1590/s1807-59322009000900006

- Yusof, Z. M. (2020, February 10). Seven Weeks jail for samurai-wannabe for terrifying MRT commuters. The New Paper. Retrieved February 23, 2022, from https://tnp.straitstimes.com/news/others/seven-weeks-jail-samurai-wannabe-terrifying-mrt-commuters

- Louisa Tang (15 September 2021). Over 5 years’ jail for chopper-wielding man who attacked elderly aunt, healthcare assistant. Today. Last retrieved 29 March 2022 from: Over 5 years’ jail for chopper-wielding man who attacked elderly aunt, healthcare assistant – TODAY

- HBO. 2022. Euphoria | Official Website for the HBO Series | HBO.com. [online] Available at: <https://www.hbo.com/euphoria> [Accessed 23 February 2022].

- Eric J Nestler (2005). The Neurobiology of Cocaine Addiction. Sci Pract Perspect., 3(1): 4–10. doi: 10.1151/spp05314

- W. Alexander Morton (1999). Cocaine and Psychiatric Symptoms. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry, 1(4): 109–113.

- Zimmerman JL (2012). Cocaine intoxication. Crit Care Clin., 28(4):517-26.

- Wong Pei Ting (2 March 2018). Real victims of war against drugs not traffickers, but innocent children: Shanmugam. Last retrieved 25 March 2022 from: https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/real-victims-war-against-drugs-not-traffickers-innocent-children-shanmugam

- Dinesh Singh Bhatia s/o Amarjeet Singh v Public Prosecutor [2005] SGHC 63

- Mike Tan and Tiffany Tan (22 January 2020). Counting the Cost: Drug Abuse and Drug Crime in Singapore. Ministry of Home Affairs. Last retrieved 2 March 2022 from: https://www.mha.gov.sg/home-team-news/story/detail/counting-the-cost-drug-abuse-and-drug-crime-in-singapore

- Central Narcotics Bureau (7 June 2021). New Release. Last retrieved 2 March 2022 from: https://www.cnb.gov.sg/docs/default-source/drug-situation-report-documents/cnb-annual-statistics-2020-final.pdf

- Psychology Today (25 October 2021). Cocaine Use Disorder. Last retrieved 2 March 2022 from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/sg/conditions/cocaine-use-disorder

Author’s Biography

Nicole Teo is currently pursuing a degree in Law and in the middle of her second year of the programme. She is aspiring to be a prosecutor one day, which sparked her interest in all things related to criminal law, including forensic science

Yangyang is currently a freshman pursuing a degree in law. He has a strong interest in all aspects of crime, including both the criminal law and the forensic elements.

Edited by: Celine Cheow and Cherylynn Tan