CJC-F Announcements, CJC-F News, Uncategorized

Behind the Scenes: A psychological perspective on testifying in proceedings

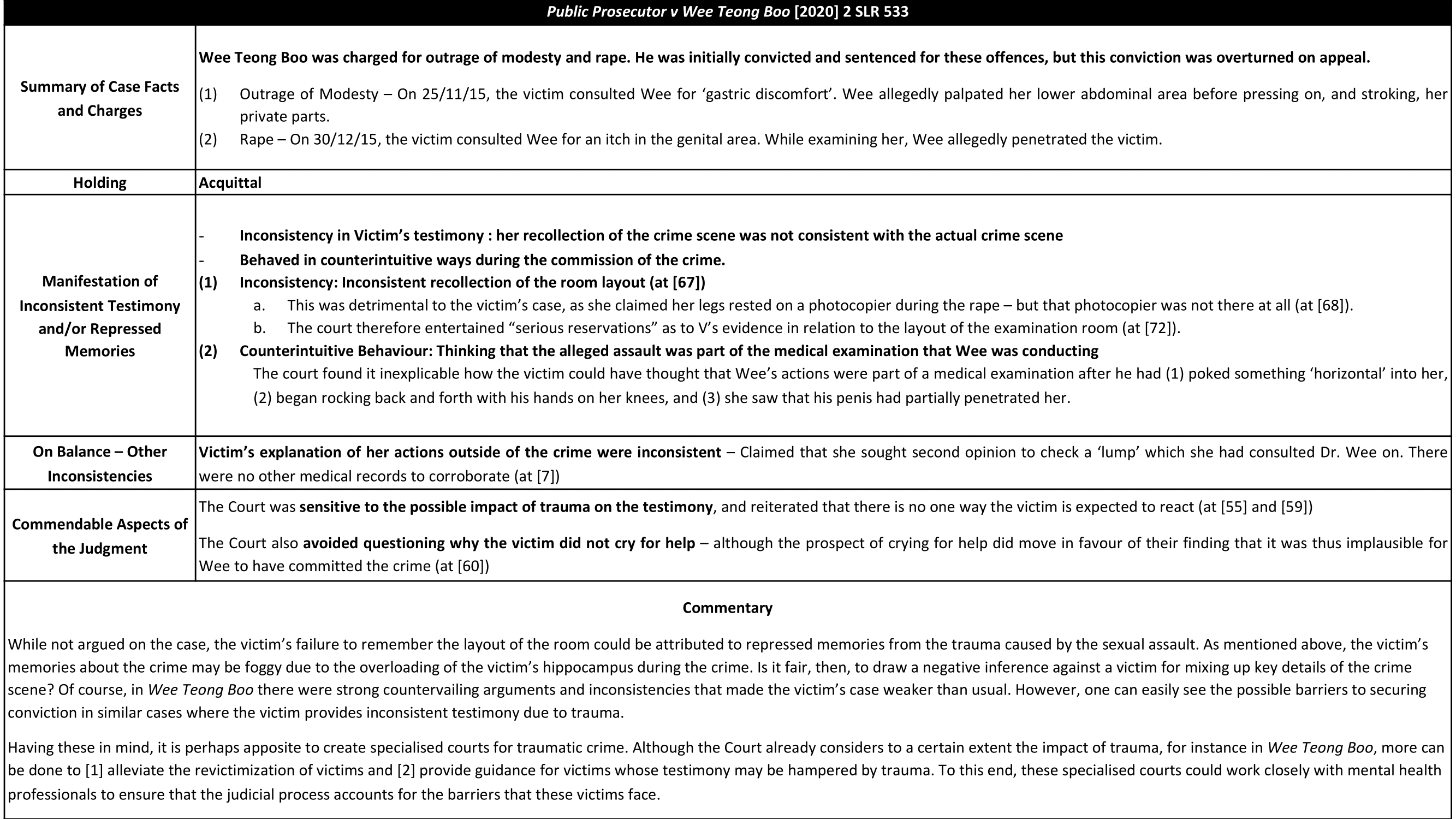

The scope of the article will cover the following: The standard of proof required to make out a criminal offense is high – and rightfully so. Conviction means jail time, which not only entails the complete deprivation of one’s liberty, but also a criminal record. Prosecutors are hence expected to prove their case against the accused person beyond a reasonable doubt. To this end, victim testimonies are always useful in proving whether or not there is indeed a single believable doubt. Here, however, is where trauma leaves its ugly shadow. A traumatic event is one where a person experiences something that is frightening and overwhelming, causing him or her to lose a sense of control. While it often amounts to a threat to someone’s ability to survive, everyone processes traumatic events differently. The psychological trauma of experiencing crimes such as sexual assault or abuse can impact the victim’s testimony in several ways – (1) Trauma may cause the victim to behave counterintuitively during the encounter, causing people to doubt their testimony about the crime, or (2) result in repressed memories which cause gaps in their testimony. These effects shall be discussed in turn. Counterintuitive Reactions to Traumatic Experiences It is common for people to have internalised stereotypes of how victims ‘ought’ to react to crimes. Consider the commission of the sexual assault described above. As the victim’s lack of consent forms the cornerstone of the crime, victims are expected to struggle, shout for help, or at least retaliate. In the context of sexual assault, these expectations can be referred to as ‘rape myths’. These expectations do not account for how trauma may cause victims to act counterintuitively, behaving in ways that militate against or are completely at odds with how one may expect a victim to behave. Specifically, traumatic threats may cause victims to freeze, dissociate, enter tonic immobility, or experience collapsed immobility instead of fighting or fleeing, as one might “rationally” expect them to. During cross-examination, rape victims may be unable to justify their inaction and may even make inconsistent statements about what they thought they were doing. If there were witnesses or surveillance footages of the crime, it may even appear that the victim consented. This gives the defence counsel and the judge room to raise doubts about their incoherent and inconsistent statements; lowering the overall reliability of their testimonies. To understand how trauma causes counterintuitive behaviours, it is necessary to discuss the neurobiological impact of trauma. The neurobiological impact of trauma manifests on two levels: (1) behavioural, and (2) cognitive. On the behavioural level, victims of traumatic crime tend to freeze when harm is inflicted on them. The neurobiological explanation for such ‘counterintuitive’ behaviour lies in how trauma impairs executive cognitive function. Specifically, when one experiences a life-threatening traumatic event, the brain’s subcortical defence circuity assumes dominance over higher brain functions, triggering automatic reactions such as freezing, fleeing or fighting. Here, however, a disambiguation is required. Contrary to popular belief, individuals cannot consciously select from either of these responses. As subcortical processes occur deep in the brain, disconnected from conscious awareness, all these responses are purely reflexive. The first reflexive response is to freeze, as this facilitates vigilance for incoming attacks while seeking possibilities to escape. Following this, the victim must assess how they can respond to the threat – however, as the experience of trauma floods the brain with stress hormones that suppress rational cognitive function, this assessment often entails a mere reflexive selection from a range of habit-based responses. As victims are often untrained in self-defence, fighting is usually not in this range of habit-based responses. If unable to flee, victims may simply freeze. This explains why some sexual assault victims do not fight back, yell or escape – counterintuitive actions to the onlooker, but perfectly comprehensible from a neurobiological perspective. On the cognitive level, victims of traumatic crime may experience difficulties in explaining their behaviour or supporting their testimonies in court. These victims often experience a loss of executive function during the commission of the crime. Stress hormones, which flood the brain following the perception of a threat, cause a rapid loss of prefrontal cognitive abilities, limiting their ability to think, plan, and reason in the face of the threat. This not only means that victims are unable to act rationally and thus more likely to freeze, but also means that victims may be unable to explain their own behaviours during and immediately after the material time of offence. Seen in this light, the victim’s testimony will often seem patchy, inconsistent, and incomplete; making it difficult to withstand cross-examination. Neurobiological alterations triggered by the crime may also impair the victims’ ability to defend themselves; further weakening the overall reliability of their testimonies. Seen in this light, the court might exercise its judicial discretion to exclude such evidence or simply assign less weight to the victims’ testimonies. In extreme cases, where the victim is unable to escape and the assault is unavoidable, extreme survival reflexes such a tonic immobility (temporary paralysis), collapsed immobility (fainting) and dissociation may be triggered after the initial freeze. Intuition will tell us that the victim’s non-resistant behaviour indicates consent. However, from a psychological perspective, the victim is experiencing the effects of the extreme survival reflexes above and could not react instinctively because of the extreme constriction of thought, movement, or speech which makes them more vulnerable to attacks like sexual assault. Trauma’s Influence on Memory and Recall A common assumption about memory is that individuals ought to be able to recollect major events with clear and unwavering accuracy. This is false, as traumatic events such as sexual assaults are encoded (recorded) differently from the routine, everyday experiences in life. Memory is fallible and has gaps and inconsistencies. To understand why this is so, a brief overview of how memory works is apposite. Memories refer to the access, selection, reactivation, or reconstruction of stored internal representations. When information is received, this information is encoded by the hippocampus and amygdala for storage as memories. This information may be encoded either as visual, acoustic, or semantic impressions, and their content depends on what the brain appraises to be more important. Additionally, fresh memories are generally fragile and can be easily disrupted unless the perceiver is given time to ‘consolidate them’ – for traumatic memories, two full sleep cycles may be required to fully consolidate the information encoded at the point of trauma. Victims, however, do not have the luxury of waiting before reporting a crime. Proof of the crime, including DNA samples and/or other circumstantial evidence, are best collected swiftly. Victims may thus be expected to give their statements shortly after experiencing a traumatic event – which may cause their initial statement to run contrary to their later statement which was made after they have processed the traumatic event. Case Study It is apposite here to note several things about this case. First, the victim’s faulty recollection of the layout of the room affected the reliability of her testimony, casting doubt on her allegations against the accused. Next, the discussion of this case is not designed to cast aspersions on the Court’s decision. Indeed, to the Court’s credit, it affirmed at [55] that there is “… no prescribed way in which victims of sexual assault are expected to act.” Additionally, the Court distinguished between a “… victim’s reaction to a sexual assault after the trauma of the incident [and] the credibility of a victim’s claim of what she thought was happening, while it was happening”. It was the lack of the latter credibility, alongside gaping inconsistencies in her testimony concerning other events distinct from the commission of the crime, that torpedoed the Prosecution’s case. Finally, it must be remembered that the standard of proof was especially high. Since the Prosecution relies very substantially on the victim’s testimony to sustain a conviction, the evidence must be unusually convincing (PP v Mohd Ariffan bin Mohd Hassan). Accordingly, the following case study is useful for its factual matrix in highlighting circumstances where repressed memories and counterintuitive actions could arise – rather than for prescriptions of how the Court ought to react. “You have a right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used in a court of law.” We often hear the Miranda warning in American dramas when the suspect is arrested. In Singapore, the “right to remain silent” is not as important. Why then is the accused’s testimony important? An accused’s testimony is just as critical as other witnesses’ testimonies in determining the truth behind what actually happened. At trial, the prosecution will attempt to impeach the accused’s credibility during cross-examination. The judge will hear all evidence presented before him and assess the credibility of each evidence. The accused may deceive investigators in an attempt to avoid conviction. One method of detecting deception is through the use of a polygraph test. A polygraph test “involves inferring deception through analysis of physiological responses to a structured, but unstandardized, series of questions” and using physiological indicators such as heart rate, respiration, and skin conductivity. In Singapore, the polygraph can be used when recommending the prosecution to proceed with a particular charge. However, it cannot be used by the prosecution as evidence admissible in court to weaken the reliability of the accused’s statements (PP v Ling Chengfeng @ Ling Koh Hoo at [103]). The polygraph test is controversial in nature. Even an honest person may suffer anxiety when being asked a series of questions which may ultimately result in inaccurate outcomes. Other controversial methods include, inter alia, voice stress analysis, narcoanalysis and hypnosis. There are no statistics to back up the claim that these tests are accurate. Polygraph tests are used “for the benefit of persons under investigations” and “no adverse inference can be drawn against the person” for refusing to take a polygraph test (PP v Lye Yoke Ping Jenn at [27]). Today, investigators are well-equipped with various methods to ‘extract’ confessions. As only voluntary statements are admissible in court, some investigators find new ways to ‘bait’ the accused. Police officers will also tend to be subjected to the same cognitive biases, such as confirmation bias, and would “have arrested you because they think you’re guilty, so nothing you say is likely to change their mind”. One method investigators use is the Strategic Use of Evidence approach where the investigator questions the suspect systematically and withholds evidence till the end of the questioning. This makes it increasingly difficult for the accused to deceive the investigator especially when the answers “contradicted the evidence possessed by the interviewer”. The inconsistencies between the interviewer’s evidence and the accused’s statements are used to detect deceit. Additionally, in cases involving co-accused persons, research was conducted on how these co-conspirators interact to deceive the investigators. Co-conspirators “who recall an actual, jointly experienced event from transactive memory do so in a different manner than two persons who are attempting to recall a fabricated event”. Consequently, to prevent himself or herself from making confessions to investigators who use psychological methods like misleading statements or other strategic methods, the accused person often chooses to remain silent in order to prevent self-incrimination. How do we then detect deception in court if polygraph tests are inadmissible in court? If the case goes to trial, the prosecution or defence counsel will attempt to discredit the witness testimony during cross-examination in order to prove their case theory. This is done either through eliciting evidence to support the counsel’s case or discrediting the witness’s affidavit of evidence-in-chief (“AEIC”) in civil cases. In criminal cases, the evidence-in-chief is given orally. The defence counsel will take up a particular line of questioning to establish that the victim’s testimony is inaccurate and unreliable due to the victim’s mistaken belief of the facts or his deliberate act of concealing the truth. The prosecution, on the other hand, will attempt to weaken the reliability of the accused person’s testimony at trial, by referring to the accused’s statements to the police and how exculpatory facts were not mentioned when long statements or cautioned statements are being taken. As a result, adverse inferences may be drawn against the accused under Section 261 of the Criminal Procedure Code (“CPC”) for his failure to mention exculpatory facts which he subsequently relies on in his defence at trial. Another way the Prosecution can weaken the reliability of the accused’s statements is to simply point out the inconsistencies in the accused person’s account of what happened when compared to the facts of the case. For example, in PP v Lau Chi Sing, the accused was charged for trafficking in diamorphine, a controlled drug, contained in the batteries in his radio cassette player. The accused claimed that he was transporting jewellery and not drugs. The judge found that his evidence was incredible as (1) he left the batteries unattended in the hotel claiming that it contained jewellery; and (2) though he was planning to seek employment in Amsterdam, his luggage did not appear to be of someone who was going overseas to take up employment. The inconsistencies in the accused person’s account of facts did not gel with the other part of his evidence adduced. In such a case, the prosecution may attempt to “poke holes” in the accused’s testimony to render it inherently incredible and therefore disregarded. Can an accused choose to remain silent and what happens if he or she remains silent? Unlike the Miranda warning which arose out of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution which provides the right against self-incrimination, the privilege against self-incrimination has become more complicated and less significant in Singapore. In PP v Mazlan bin Maidun at [19], the court held that a failure to inform the accused of the right to remain silent was not part of his constitutional rights. Although an accused is not compelled to give evidence in any criminal proceedings under Section 122(3) of the Evidence Act, Section 22(2) of the CPC requires a person to truly state what he knows of the facts and circumstances of the case except incriminating facts. Sections 23 and 261 CPC states that if the accused does not raise facts on record during the police investigations and subsequently raises exculpatory facts later during trial, the judge may be less likely to believe him or her and the court may draw adverse inferences against the accused. It was noted by the courts in Haw Tua Tau v PP at [21] that while drawing adverse inferences, the inference drawn should “depend on the circumstances of the case”. Failure to provide evidence is not conclusive of guilt but can give rise to negative inference if the situation clearly calls for an explanation. This was shown in Chai Chien Wei Kelvin v PP at [83] where the Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal and held that the appellant was guilty of abetment of exporting drugs for his failure to call for any evidence. However, where the accused’s mental condition makes it undesirable for him to be called upon to give evidence, adverse inference should not be drawn (Took Leng How v PP at [44]). Courts should tread carefully where the accused alleges that he suffers from a mental condition. It is found that there exists a fine line between pleading mental illness and legal malingering, especially for undiagnosed sufferers of Munchausen’s syndrome. Research has been conducted to show that pathological individuals suffering from Munchausen’s syndrome seek “to avoid or mitigate a punitive response”. Essentially, these individuals feign illnesses to diminish their responsibility for their actions. Hence, courts may adduce expert evidence such as psychiatric evidence to determine the falsity of the confession (R v Blackburn at [28]), and the admissibility of the accused’s confession. False confessions Accused persons may be duped into giving false confessions due to three main reasons: Has this improved the overall reliability in the accused’s statements? During the 2018 Parliamentary Debates, Nominated Member of Parliament Mr Kok Heng Leun highlighted that threat, inducement or promise could be made prior to the video-recording and thus not captured on camera. He proposed that the entire interrogation process between the police and the suspect be recorded on camera. In addition, VRIs may be compromised where the frame only focuses on the accused’s face but not his other parts of his body. His body language, which was not captured in the video, could indicate signs of distress. This could lead to the misclassification error or fundamental attribution error mentioned above. Interview room of the One-Stop Abuse Forensic Examination Centre All in all, it remains to be seen how the law will be developed to introduce new methods of detecting deception. Having a suspect’s statement immediately recorded when he or she is arrested is a good first-step in promoting positive change to curb false confessions and mitigates the issue of admissibility of such statements. However, more needs to be done to prevent possible manipulations or compromise of VRIs. A possible solution would be to set up multiple cameras covering different angles of the interrogation. Lawyers as well as judges can also be trained through different forums on how to deal with VRIs. Only time will tell if the reliability of the accused’s statements and the efficacy of the interrogation process will be better off with the introduction of VRIs. For a long time, children’s testimonies have had its credibility repeatedly doubted in the courts of law. When a child experiences and reports traumatic events, forensic interviews, which are neutral and professional, could be utilised to investigate allegations. Undergoing forensic interviews and even being involved in the litigation process in general can be a confusing experience for everyone, especially children. Section 120 of the Evidence Act provides that all persons shall be competent to testify unless the court considers that they are prevented from understanding the questions put to them or from giving rational answers to those questions by tender years, extreme old age, disease, whether of body or mind or any other cause of the same kind. It does not lay down an age restriction on children giving testimony and the test is therefore one of whether they understand the questions put to them and are able to provide rational answers. The views on the credibility of child testimonies are extremely divided in the society. It is of no remote surprise that people view child testimonies to be not credible as the general public deems that child witnesses are highly susceptible to potential suggestibility. This occurs when a person, not just children develop false memories after being subjected to repeated, suggestive questioning. In practice, there is a greater likelihood that a child will be repeatedly questioned about an event, by investigators and parents alike. Many also take children’s testimonies with a pinch of salt as children have not developed clear concepts of time, distance and space, neither are they fully developed linguistically. For example, they will not be able to accurately answer questions about the number of times that an often-repeated event occurred, because they lack counting and computation skills. Since young children often feel socially compelled to attempt answering questions, they tend to guess when they are unsure, or attempt to form a logical answer from the parts they are able to understand. This would result in their answers to questions seeming unresponsive, misleading at trial. On other occasions, they are not able to express themselves and articulate their thoughts to elicit meaningful testimony as well as adolescents and adults due to their lack in linguistic abilities. In the courtroom, questions posed to child witnesses are often complex and hard to understand, containing complicated grammatical constructions (for example, “if he told the police that that was what he thought you wanted to do, are you saying that you don’t think he could have thought of that?”). Such questions could already pose difficulties in comprehension for adolescents, much less for young children. Many legal practitioners also believe that it is unnecessary to adjust their language when examining children aged 10 to 12. This overestimation of language competencies also gives rise to confusion, and hence inaccuracies to their testimonies. Anxiety and stress are two extremely common emotions felt by child testifiers in court, which adversely impacts the quality of the child’s statements as evidence. Children often describe the cross-examining process to be the most stressful part of the trial, which adds on to the stresses testifying in court itself. The feelings of anxiety can stem from facing the accused, being questioned by lawyers, and being in a formal courtroom setting. In most cases, children are brought to trial by unfamiliar adults and at other’s demands, rather than their own voluntariness to tell. Due to a child’s developmental period and their lack of self-agency, children may feel anxious, nervous, and/or reticent. Such interactions place a large amount of emotional stress on the child witness and could impair his or her ability to think and communicate effectively. Albeit the abovementioned factors, the credibility of child testimonies should not be understated, especially when children are the victims. Many may neglect the fact that child abuse takes places in circumstances that closely mirror the suppression and repression of a conspiracy. In most cases of child abuse, the victims are violated by familiar adults, usually of authority whom they trust. The abusers then exploit the victims’ unwavering loyalty and tendency towards secrecy, usually through emotional manipulation and threats. Such manipulations induce fear and repression-based shame to ensure the victims hush up about the abuse, which mirrors what co-conspirators do. By overcoming the pressure toward secrecy to describe the abuse, the spontaneous hearsay statements of a child victim resemble co-conspirators’ statements at least to the extent that, if co-conspirator statements are admissible, child victims’ statements fitting traditional hearsay exceptions also should be admissible. It could in fact, be more credible than it appears to be as children are more honest than adults. They are less likely to deceive due to their innocence and lack of motive. Despite claims of children being unreliable due to poor memory retention, studies have shown that a child’s memory improves vastly with age. Children over four years old reveal almost adult-level recognition memory performances. Furthermore, children are not only good observers, but are also perhaps more objective than adults. Another study concluded that child witnesses make for the best witnesses in simple events. People may think otherwise as children tend to struggle with translating visual to verbal accounts but taking a different approach in answering questions does not necessarily mean that such accounts are worse than that in adults. Since there is significant value in an accurate child testimony, we now explore how to best elicit meaningful and credible responses from a child witness. Use of Demonstrative Evidence Legal practitioners could explore the use of demonstrative evidence. Since it was previously explained that a child may not have developed competent spatial awareness and linguistic abilities, providing children with visual cues for them to relate to proves to be extremely useful. Demonstrations are usually permitted on both direct and cross-examination. However, it is to note that such demonstrations are to be used as a form of relation or communication, instead of direct evidence. This form of evidence is probably more accurate than that obtained by asking leading questions. Testimonies elicited in this form would need to be supplemented, by explanatory statements of the attorney examining the witness, but is nevertheless an effective method. Intervention of Child Psychologists A child psychologist could be employed to prepare a child witness for court hearings as emotional factors or psychological blocks induced by shyness or apprehension may render the child quite unresponsive in the courtroom. The psychologist could also advise and suggest counsels and attorneys with the most effective means of eliciting testimonies. Usually, such interviews could be done in judges’ chambers or in a room that a child would feel safe in, facilitated by closed-circuit surveillance systems (“CCTV”). During the court process, closed courtrooms and prior orientation to the court and process may be beneficial to the child as well. Utilisation of Trauma-Informed Approach Furthermore, a good point to note is that when legal practitioners or relevant stakeholders work with children through any forensics and/or court proceedings, specific characteristics of this population should be considered to utilize a trauma-informed approach. Working with children through the forensics and/or court processes can be more effective and sensitive if professionals are trauma-informed. In such settings, if the underlying trauma is not recognized or even not responded to appropriately, the chances of re-traumatization are increased. Professionals should also take into consideration the child’s developmental level (id est their developmental abilities), the child’s mode of communication, and should never attempt to force a disclosure or continue when a child becomes distressed. Such force may re-traumatize the child. One may consider additional, non-duplicative interviews. In Singapore, a toolkit of how to better cross-examine vulnerable witnesses is made readily available for practitioners in the Best Practices Toolkit published by the Law Society of Singapore in 2019 for the cross-examination of vulnerable witnesses, which includes children. Notably, it is crucial to place emphasis on ensuring that the child witness is clear about the questions being asked and is not being pressured into an answer that one is unsure of. Furthermore, it is important to be aware of one’s own body language, as well as the witnesses’, then adjusting the cross-examination accordingly. Practitioners should also not restrict a child witness’ testimony strictly to words as oftentimes, they would be able to better narrate their observations via gestures. Understandably, one may interpret seemingly ambiguous gestures in various ways. Hence, it would be helpful to clarify with the witness when in doubt to ensure clarity. Child testimonies, despite its stereotype of being unreliable, has proven to be useful and credible in a myriad of situations. Such testimonies may even advance or detriment cases significantly. It is paramount for practitioners and experts to appreciate that there are certain techniques, as explored above, to better elicit a meaningful response from children. There is no one-size-fit-all method in examining child witnesses, and exceptional care must be taken when examining children who have been through traumatic events. Legal Reforms During the Second Reading of the Criminal Justice Reform Bill in 2018, then Senior Minister of State for Law, Ms Indranee Rajah, proposed amendments to the CPC and other statutes as she recognised a need for a more progressive and balance criminal justice system. The following changes were made after the Criminal Justice Reform Act was passed in 2018: Over the years, courts have found ways when dealing with issues of credibility of witnesses’ testimonies and will often err on the safe side. Legal reform by the Singapore Parliament is aimed towards minimising the trauma of child witnesses and victims of sexual abuse. With the development of technology and continuous forensic research conducted on the psychology behind the testimonies, courts can therefore rely on the help of expert witnesses or forensic psychologists to decipher inconsistent testimonies – whether due to trauma, age or otherwise.

We often observe various witnesses being called up to stand to provide evidence or recollection of what transpired, during and after a crime had taken place. In this article, we will attempt to explain the psychology and law behind such testimonies.

(i) Traumatic Testimony: Not an Episode of Suits“Rape myths add up to create a typical “good case” that will win in court… in the prototypical ‘good’ rape case, the victim […] is grabbed from behind by a man she’s never seen before […] Her assailant has a knife, a gun, and brass knuckles. He breaks her jaw by punching her, so she can’t scream, and stabs her at least once […] She fights back forcefully nonetheless, and the struggle attracts the attention of a male police officer, who arrives and pulls the man off of his victim”

https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/psychpedia/trauma

https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/psychpedia/trauma

Trauma may also impair the victim’s ability to recall specific details about the crime such as the chronology of events leading to the offence, the location of the offence and the victim’s own state of mind. This will weaken the overall reliability of the victim’s testimony as the veracity of the victim’s conflicted, fragmented and sometimes blurry account of events to the police is being questioned.

This process of memory-creation can however be disrupted by traumatic experiences. Specifically, the stress hormones produced upon activation of the brain’s defence circuitry kicks the amygdala into overdrive, heightening traumatic memories by focusing attention on a few details at the expense of others. It also overstimulates the hippocampus, which initially experiences a burst of enhanced memory storage and creates “flashbulb memories”, but later experiences temporary impairment from all the stress. Seen in this light, “fragmented” memories are created when the brain performs minimal encoding. When a victim is called to the stand, he or she may proffer a patchy or inconsistent account of the facts leading to the commission of the offence– where key elements of the crime contradict with the objective evidence at hand.

The circumstances of Public Prosecutor v Wee Teong Boo well illustrate the above concerns – especially that of repressed memories and counterintuitive actions.

General Practitioner Wee Teong Boo https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/doctor-wee-teong-boo-sexual-assault-12579566

https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/doctor-wee-teong-boo-sexual-assault-12579566

The act of testimony on the witnesses’ stand, followed by the process of cross-examination by a quick-witted defence counsel, is probably one of the most well-known aspects of a criminal trial. Consider, indeed, popular dramas such as ‘Suits’ or in documentaries such as ‘When They See Us’. Effortlessly gripping and absorbing, they often leave us at the edge of our seats. What these depictions leave out, however, is how trauma impacts the victim’s testimony, and how the very act of testifying can lead to further psychological trauma later in the victim’s life. The study of forensic psychology shed light on these kinds of trauma and deciphers the seemingly disjointed testimonies offered by victims in court. Indeed, and to take a leaf from AWARE’s book, the use of specialised courts or investigators with a background in forensic psychology may help alleviate the experiences of these victims of traumatic crime.

(ii) Evaluating the Reliability of the Accused’s TestimonyPolygraph Test

https://www.vox.com/2014/8/14/5999119/polygraphs-lie-detectors-do-they-work

https://www.vox.com/2014/8/14/5999119/polygraphs-lie-detectors-do-they-work

Methods investigators use to ‘extract’ confessions

https://www.straitstimes.com/politics/parliament-video-recorded-interviews-other-changes-to-criminal-justice-system-approved

(iii) Children’s Testimonies

https://news.usc.edu/130445/usc-law-professor-launches-nations-first-project-on-child-witness-testimony/

1. Video-recording of interviews. As mentioned above under (ii) Evaluating the Reliability of the Accused’s Testimony, the CPC was amended to include section 40A, where an officer can record a statement during an investigation through an audiovisual recording.

2. Enhanced protection of victims of child or sexual abuse cases in open court.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

Authors’ Bibliography

Tyronne Toh is a Year 4 undergraduate at Yale-NUS College & NUS Law. Tyronne is part of the Forensic Psychology team, and is pursuing a double degree in Law and Liberal Arts with a minor in Global Affairs. He is interested in criminal legal process, learning about the administration of justice in Singapore, and intrigued by forensic crime scene investigation.

Comane Tan is a Year 2 Life Sciences undergraduate with minors in Forensic Science and Psychology and plans to do the Juris Doctor programme upon graduation. She is is a member of NUS Criminal Justice Club – Forensics under the Forensic Psychology Division. She is interested in how different disciplines in Forensic Science aids in different stages of criminal proceedings. Her other interests includes forensic crime scene investingation, criminology and investigative psychology.

Bryan Ho is a Year 1 undergraduate currently pursuing a degree in Law in NUS and is a member of NUS Criminal Justice Club – Forensics. As part of the CJC-F “Forensic Psychology” project, Bryan has helped with the research and writing of articles, along with producing awareness sharing posts for its social media page. Ever since joining CJC-F, his interest in forensic psychology has grown and he aspires to horne his skills in the area in his pursuit for the truth. His other areas of interest are courtroom psychology and investigative psychology. Jing Jie is a 3rd Year Law Undergraduate minoring in Political Science. He has a deep interest in exploring the various ways behaviioural psychology has been applied in legal settings (interrogation room, courtroom). As one of the project managers of CJC-F (Psychology Division), he is in charge of planning and executing various projects. As a member of the editorial team, he curates, edits and delivers new content for CJC-F’s weekly newsletter publication and social media outreach. As a firm believer in ensuring fairness for all in the criminal justice system, Jing Jie explores how the study of forensic psychology can help law enforcement officers, lawyers and judges make better decisions. He hopes that the articles, social media posts and seminar will generate awareness, develop empathy and shed light on the problems surrounding offenders with mental disorders, traumatic victims and vulnerable witnesses.

Jing Jie is a 3rd Year Law Undergraduate minoring in Political Science. He has a deep interest in exploring the various ways behaviioural psychology has been applied in legal settings (interrogation room, courtroom). As one of the project managers of CJC-F (Psychology Division), he is in charge of planning and executing various projects. As a member of the editorial team, he curates, edits and delivers new content for CJC-F’s weekly newsletter publication and social media outreach. As a firm believer in ensuring fairness for all in the criminal justice system, Jing Jie explores how the study of forensic psychology can help law enforcement officers, lawyers and judges make better decisions. He hopes that the articles, social media posts and seminar will generate awareness, develop empathy and shed light on the problems surrounding offenders with mental disorders, traumatic victims and vulnerable witnesses.