CJC-F, CJC-F Announcements, CJC-F Understanding Forensics

Fingerprints: Leaving Behind Traces of Identity

Introduction

One of the primary objectives in forensic science is to answer the question of “who” was present at the crime scene, and possibly by extension, responsible for the crime. Like DNA, fingerprints are often conceived by the masses as an infallible method to nail the perpetrator of a crime. Criminal investigation in law enforcement television shows often present scenes of forensic scientists, fully clad in light blue protective suits, dusting the handles of doors and windows for fingerprints and meticulously analysing the trace remnants of the culprit’s identity with a magnifying glass. Fingerprint analysis in reality, does not deviate too far from what is shown on these shows. Crime scene investigators look out for latent fingerprints, which are fingerprints left behind mainly due to perspiration on the fingers and thus hardly visible to the naked eye, and develop them with fingerprint powders before collection for subsequent analysis.

One of the primary objectives in forensic science is to answer the question of “who” was present at the crime scene, and possibly by extension, responsible for the crime. Like DNA, fingerprints are often conceived by the masses as an infallible method to nail the perpetrator of a crime. Criminal investigation in law enforcement television shows often present scenes of forensic scientists, fully clad in light blue protective suits, dusting the handles of doors and windows for fingerprints and meticulously analysing the trace remnants of the culprit’s identity with a magnifying glass. Fingerprint analysis in reality, does not deviate too far from what is shown on these shows. Crime scene investigators look out for latent fingerprints, which are fingerprints left behind mainly due to perspiration on the fingers and thus hardly visible to the naked eye, and develop them with fingerprint powders before collection for subsequent analysis.

What are Fingerprints?

Fingerprints are biological features unique to every individual. Similar to DNA, fingerprints are valuable evidence employed in law enforcement to identify and establish a connection between persons and the scene of crime. The use of body parts as a means to distinguish the accused from the innocent is not new and dates back to the development of anthropometry or the “Bertillonage” system by Alphonse Bertillon. The measurements of 11 body parts of individuals were carried out and recorded. However, the Bertillonage system often encountered variations in measurements as operators did not have a standard method of measuring body parts. Fingerprints, on the other hand, were found to consist of ridge patterns that do not change even after a long time. Later, it was also recognised that the ridge features were unique, rendering fingerprint classification more robust than the Bertillonage system.

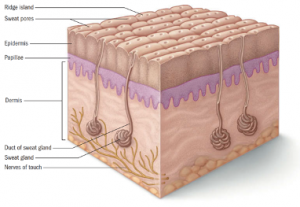

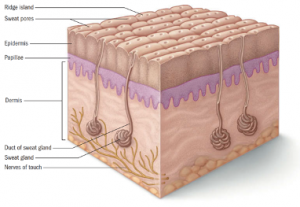

Figure 1. Cross-section of human skin

Principle of Permanence and Uniqueness

The biological basis of fingerprints which gives rise to characteristic ridge patterns stem from two principles – permanence and uniqueness. The principle of permanence provides that the patterns of the ridges on the finger remain unchanged throughout one’s lifetime. This is due to structural elements of the skin that allow epidermis cells to rise together from the dermal papillae which determines the unique cell arrangement and production of the landscape the cells emerge from. The principle of uniqueness states that no two fingerprints are identical, even in twins with identical DNA profiles. It is because formation of the ridges begins at the foetal stage and placement of detail (or minutiae) is governed by interdependent environmental stress across the particular area of skin at a specific time. Therefore, both genetic and environmental factors can affect the formation of ridges (raised portions) and furrows (depressed portions) on the fingers of an individual, leading to unique fingerprints.

Fingerprint Matching in Criminal Identification

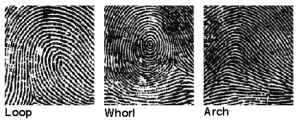

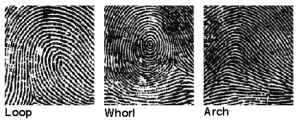

Photo taken from Art Ed: Middle School 5-8 by Tiffany Horton.

The process of fingerprint pattern analysis is usually defined by the ACE-V system – analysis, comparison, evaluation and verification. The first step begins with ascertaining the suitability of the recovered fingerprints by examining the quantity and quality of the ridge patterns. Next, the fingerprint examiner proceeds to compare the fingerprints recovered from the crime scene with that taken from a suspect or other reference by scrutinising the similarities and differences in the major pattern as well as minor detail. The Henry’s classification of fingerprints provides a systematic method of categorising fingerprints into 3 major patterns – loops, whorls, and arches. Approximately 60%, 35% and 5% of fingerprint patterns fall into the loops, whorls and arches respectively. The fingerprint examiner then examines second and third level details such as the minutiae in the fingerprints, which are characteristics pertaining to an individual and therefore enables individualisation. Lastly, the results are then evaluated in a report and the same fingerprint samples are sent to other examiners for cross-verification.

Chi Tin Hui v PP

Facts: The defendant was found in possession of a gift-wrapped cardboard box which contained diamorphine, a class “A” controlled drug. The defendant was subsequently charged with the offence of trafficking under s 5(a) of the Misuse of Drugs Act.

Holding and explanation: Convicting the defendant of trafficking, the court reasoned that an impression of his middle finger was found on the gift-wrapping paper. This gave rise to the inference that the defendant had wrapped the drugs with the gift-wrapping paper to give it the appearance of a gift or present. Furthermore, the defendant’s oral statements indicated that he knew what he was carrying and this formed part of the transaction of carrying the drugs.

In the absence of any applicable defences (namely, agent provocateur and entrapment), the defendant was convicted and sentenced to death.

Mohd Sulaiman v PP

Facts: The defendant stabbed the 65-year-old victim to death with a screwdriver at a coffeeshop. The defendant was subsequently charged with murder under s 300 of the Penal Code.

Holding and explanation: Convicting the defendant of murder, the court reasoned that the fingerprint marks found on the handles of a beer crate, and a cigarette packet taken from the drawer of the drinks stall bore similarities to that of the defendant. This effectively placed the defendant at the scene of the crime. The fact that the defendant inflicted the wounds with considerable force established both the actus reus as well as the mens rea (i.e. intention to cause injuries that were sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death).

In the absence of any applicable defences (namely, intoxication, private defence, provocation, sudden fight and diminished responsibility), the defendant was duly convicted.

Conclusion

Fingerprints are not useful only in telling who was present at the scene of crime. At the same time, they can also provide information of “what” and “how” an event had happened. For instance, the direction of the fingerprints belonging to a victim found on a murder or assault weapon (such as a knife) left in his hands may unveil if it the incident was a genuine case of suicide or an act of covering up a murder. Fingerprints left on a murder or assault weapon may also assist crime scene investigators in re-enacting how the tool was used by the perpetrator to inflict injury on the victim, and establish if there was intent to cause harm. Together with other evidence, fingerprints are vital in laying out the elements to corroborate an act of crime.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

Fingerprints are not useful only in telling who was present at the scene of crime. At the same time, they can also provide information of “what” and “how” an event had happened. For instance, the direction of the fingerprints belonging to a victim found on a murder or assault weapon (such as a knife) left in his hands may unveil if it the incident was a genuine case of suicide or an act of covering up a murder. Fingerprints left on a murder or assault weapon may also assist crime scene investigators in re-enacting how the tool was used by the perpetrator to inflict injury on the victim, and establish if there was intent to cause harm. Together with other evidence, fingerprints are vital in laying out the elements to corroborate an act of crime.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

References

- Andrew R. W. Jackson & Julie M. Jackson. 2017. Forensic Science, 4th Pearson.

- Richard Saferstein. 2018. Criminalistics: An Introduction to Forensic Science, 12th Pearson.

Authors’ Biography

Associate Professor Stella Tan has postgraduate qualifications in law and science from NUS, and a postgraduate forensic science qualification from the Henry C. Lee Institute of Criminal Justice and Forensic Science, where she graduated top of her class under the tutelage of Dr Henry Lee, a renowned forensic expert in the United States of America. Prior to joining NUS in 2018 as a full-time faculty member, she was a Deputy Senior State Counsel at the Attorney-General’s Chambers where she was the lead prosecutor for a wide range of cases, including murder, sexual assault and drugs, and later Director (Prosecution and Legal Policy) at the Health Sciences Authority (HSA), where she provided legal advice and practical training to forensic experts. Prof Stella Tan is currently the Director of the Forensic Science undergraduate and postgraduate programmes at the Faculty of Science. She runs modules in both the Faculty of Law and the Faculty of Science. The modules which Prof Tan teaches are as follows: LSM1306 Forensic Science, SP3202 Evidence in Forensic Science, SP4261 Articulating Probability and Statistics in Court, SP4262 Forensic Human Identification, SP4263 Forensic Toxicology and Poisons, SP4264 Criminalistics: Evidence and Proof, SP4265 Criminalistics: Forgery Expose with Forensic Science, SP4266 Forensic Entomology, FSC5199 Research Project in Forensic Science, FSC5101 Survey of Forensic Science, FSC5201 Advanced CSI Techniques, FSC5202 Forensic Defense Science, FSC5203 Digital Forensic Investigation, FSC5204 Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, FSC5205 Forensic Science in Major Cases and LL4362V/FSC4206 Advanced Criminal Litigation – Forensics On Trial. Prof Stella Tan is also the Principal Investigator of the NUS Forensic Science Laboratory, where her collaborators include the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Singapore Police Force and Central Narcotics Bureau. Her interest in nurturing students has won her Dean’s Meritorious Teaching Awards as well as the Best Supervisor award for Undergraduate Research Opportunities.

Associate Professor Stella Tan has postgraduate qualifications in law and science from NUS, and a postgraduate forensic science qualification from the Henry C. Lee Institute of Criminal Justice and Forensic Science, where she graduated top of her class under the tutelage of Dr Henry Lee, a renowned forensic expert in the United States of America. Prior to joining NUS in 2018 as a full-time faculty member, she was a Deputy Senior State Counsel at the Attorney-General’s Chambers where she was the lead prosecutor for a wide range of cases, including murder, sexual assault and drugs, and later Director (Prosecution and Legal Policy) at the Health Sciences Authority (HSA), where she provided legal advice and practical training to forensic experts. Prof Stella Tan is currently the Director of the Forensic Science undergraduate and postgraduate programmes at the Faculty of Science. She runs modules in both the Faculty of Law and the Faculty of Science. The modules which Prof Tan teaches are as follows: LSM1306 Forensic Science, SP3202 Evidence in Forensic Science, SP4261 Articulating Probability and Statistics in Court, SP4262 Forensic Human Identification, SP4263 Forensic Toxicology and Poisons, SP4264 Criminalistics: Evidence and Proof, SP4265 Criminalistics: Forgery Expose with Forensic Science, SP4266 Forensic Entomology, FSC5199 Research Project in Forensic Science, FSC5101 Survey of Forensic Science, FSC5201 Advanced CSI Techniques, FSC5202 Forensic Defense Science, FSC5203 Digital Forensic Investigation, FSC5204 Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, FSC5205 Forensic Science in Major Cases and LL4362V/FSC4206 Advanced Criminal Litigation – Forensics On Trial. Prof Stella Tan is also the Principal Investigator of the NUS Forensic Science Laboratory, where her collaborators include the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Singapore Police Force and Central Narcotics Bureau. Her interest in nurturing students has won her Dean’s Meritorious Teaching Awards as well as the Best Supervisor award for Undergraduate Research Opportunities.  Zheng Yen Phua is a teaching assistant for the Forensic Science programmes at the Faculty of Science. He holds an honours degree in science from NUS and is currently a doctoral researcher. The modules which he is actively involved in teaching are: LSM1306 Forensic Science, SP3202 Evidence in Forensic Science, SP4261 Articulating Probability and Statistics in Court, SP4262 Forensic Human Identification, SP4263 Forensic Toxicology and Poisons, SP4264 Criminalistics: Evidence and Proof, SP4265 Criminalistics: Forgery Expose with Forensic Science, SP4266 Forensic Entomology and LL4362V/FSC4206 Advanced Criminal Litigation – Forensics On Trial. He also received Honourable Mention as Expert Witness for the NUS Forensic Science Expert Advocacy Cup 2020.

Zheng Yen Phua is a teaching assistant for the Forensic Science programmes at the Faculty of Science. He holds an honours degree in science from NUS and is currently a doctoral researcher. The modules which he is actively involved in teaching are: LSM1306 Forensic Science, SP3202 Evidence in Forensic Science, SP4261 Articulating Probability and Statistics in Court, SP4262 Forensic Human Identification, SP4263 Forensic Toxicology and Poisons, SP4264 Criminalistics: Evidence and Proof, SP4265 Criminalistics: Forgery Expose with Forensic Science, SP4266 Forensic Entomology and LL4362V/FSC4206 Advanced Criminal Litigation – Forensics On Trial. He also received Honourable Mention as Expert Witness for the NUS Forensic Science Expert Advocacy Cup 2020. Hariharan Ganesan is a Y2 student at the NUS Faculty of Law. He is currently pursuing his interest in criminal law working as a research assistant for Assistant Professor Cheah Wui Ling. He is currently a Project Manager in CJC Forensics, heading the publication Initiations: A Glimpse into Forensics. Beyond school, Hariharan volunteers as a Silver Generation Ambassador, reaching out to Merdeka Generation seniors on the Merdeka Generation Package. In his free time, Hariharan enjoys playing squash recreationally.

Hariharan Ganesan is a Y2 student at the NUS Faculty of Law. He is currently pursuing his interest in criminal law working as a research assistant for Assistant Professor Cheah Wui Ling. He is currently a Project Manager in CJC Forensics, heading the publication Initiations: A Glimpse into Forensics. Beyond school, Hariharan volunteers as a Silver Generation Ambassador, reaching out to Merdeka Generation seniors on the Merdeka Generation Package. In his free time, Hariharan enjoys playing squash recreationally.