CJC-F Announcements, CJC-F News, CLD Criminal Law Basics

Justice vs Mercy: Dealing with mentally ill offenders

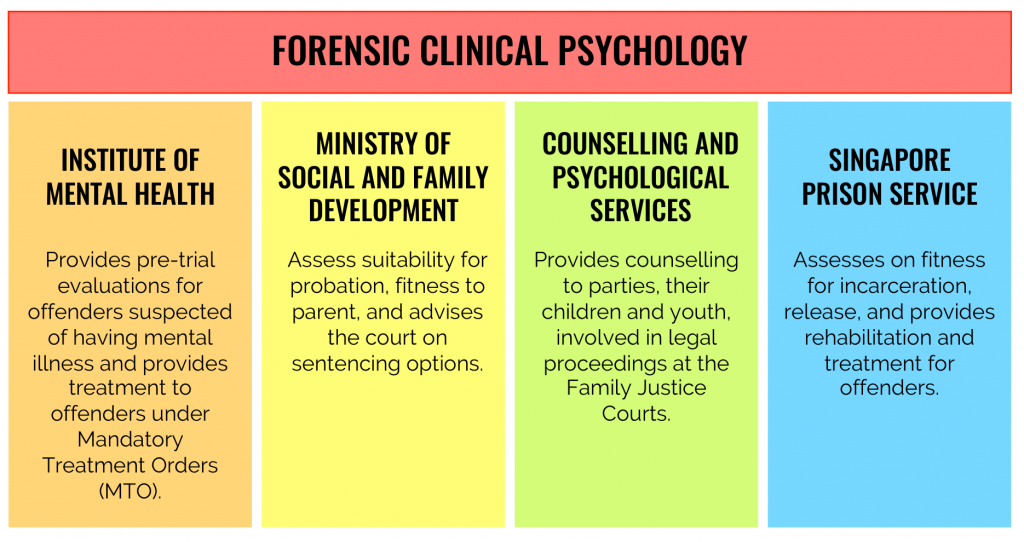

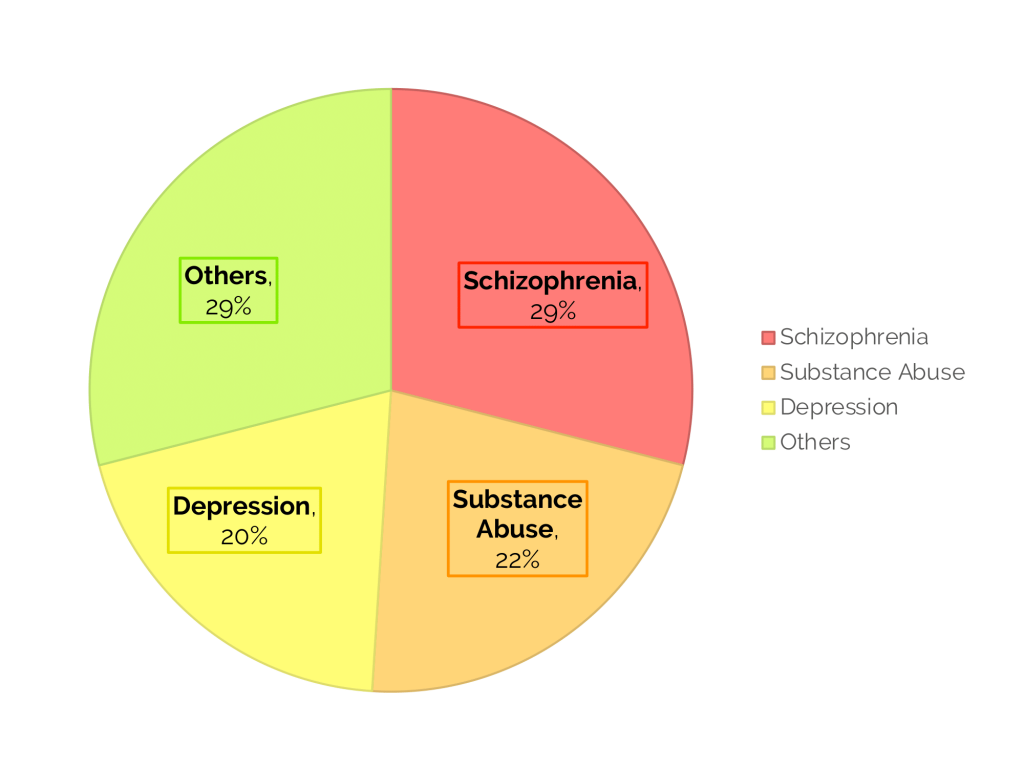

Forensic clinical psychology (FCP) is a sub-field of forensic psychology, which focuses on providing assessments and treatments for mental health issues in legal settings. The nature of FCP tends to be clinically-oriented, which includes risk assessments, rehabilitations, family conferences, interventions for juvenile offenders, therapy and treatment of offenders, and counselling for victims of child abuse or domestic violence. In Singapore, clinical forensic psychology is organised and practised mainly in four critical governmental departments and institutions. The Singapore Prison Service (SPS), which informs on fitness for incarceration and release, the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) assesses suitability for probation, fitness to parent, and advises on sentencing options. The Counselling and Psychological Services (CAPS), provides counselling to parties, their children and youths who have legal proceedings at the Family Justice Courts. Lastly, the Institute of Mental Health (IMH) provides pretrial evaluations for offenders suspected of having mental illness and capacity evaluations, as well as treatment for offenders under Mandatory Treatment Orders (MTO). An essential application of clinical forensic psychology would be that of mental health assessments. At the pretrial stages, the court may order any accused individuals suspected to be of unsound mind to be remanded for an inpatient psychiatric assessment. This assessment is done either at the Changi Prison Complex or IMH. An average of 700 to 800 inpatient pretrial assessments are ordered annually, with a noticeable increasing trend over the past few years. The pretrial assessment evaluates individuals’ competency to stand trial and the degree of criminal responsibility for their actions. An individual is fit to stand trial if he or she can understand the charges brought against them, the potential consequences, and the difference between a plea of not guilty versus guilty, instruct counsel and follow the evidence in court. On the other hand, an individual is criminally responsible if he or she was aware of their actions’ nature and intent and was aware that their actions were wrong. At the pre-sentencing stage, the defense counsel may initiate psychiatric assessments, to present mental disorders as a mitigating factor. The court may also mandate evaluating the accused’s mental health to determine his suitability for a Mandatory Treatment Order (MTO). The MTO is a non-custodial community-based sentence introduced in 2010 as an alternative sentence for offenders with mental conditions, where offenders have to commit to mental health treatment in place of a prison sentence for up to 2 years and commit to regular follow-ups and reports to the courts. Another critical application of forensic psychology is in mental disorder defences. Evidence that an accused person suffered a mental disorder episode at the material time of an offence and that their psychiatric symptoms contributed to their crime may result in a less severe sentence by the court. Findings of forensic psychiatrists and psychologists are used to make such judicial determinations. As there is a greater emphasis on mental disorders in criminal defences, the need for forensic psychiatric opinions to assist the court grows substantially too. This article limits such assessment to the defence of unsoundness of mind (s 84 of the Penal Code) and insane automatism (s 84(c) of the Penal Code). Unsoundness of mind is a defence invoked by an accused who acted while suffering from a disease of the mind (s 84 of the Penal Code). S 84 states that “Nothing is an offence which is done by a person who, at the time of doing it, by reason of unsoundness of mind is incapable of knowing the nature of the act or that what he is doing is wrong or is completely deprived of any power to control his actions.”. In this case, the defense counsel argues that the accused is either unable to appreciate the nature of the act, incapable of knowing what he is doing is wrong (by objective standards) or is deprived of the power to control his actions. Hence, he should not be convicted and punished for the crime charged. Instead, he should be legally required to seek medical aid through a special judgement. Hence an unqualified acquittal would be the proper outcome. In court, the defence hinges on establishing legal insanity and not clinical insanity. The court will refer to clinical evidence to assess whether the accused was legally insane at the alleged criminal act commission. Such evidence usually requires a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th Edition (DSM-5) diagnosis of a psychotic disorder. However, while medical evidence is essential, it is not the final word as courts can make a finding that an accused was not of unsound mind under s 84 without medical evidence (noted in PP v Han John Han [2007] 1 SLR(R) 1180). Courts may even reject medical evidence with differing expert opinions (Tengku Jonaris Badlishah v PP at [71]). However, in practice, such evidence is usually necessary to help the court understand the accused’s mental illness’s effect on their cognitive and volitional abilities. Embedded in the unsoundness of mind defence is the defence of insane automatism, covered under S84(c). It states that “Nothing is an offence which is done by a person who, at the time of doing it, by reason of unsoundness of mind is completely deprived of any power to control his actions.”. Automatism broadly refers to a state of defective capacity to control one’s conduct in which a person performs unwilled acts (see PP v Kenneth Fook Mun Lee [No 2]), and it is related to the concept of voluntariness. Insane and sane automatism is differentiated by its cause and the potential for recurrence of the conditions. The Singapore High Court (SGHC) has held that “In general, a person is not liable for involuntary behaviour for the simple reason that he or she has not done anything.” (see Koh Jing Kwang v PP at [43]). Hence, deterring an involuntary act is impossible, and such an actor does not need incapacitation or rehabilitation. To invoke the s 84(c) defence, the defense counsel must prove that the accused’s mental dysfunction must be due to a disease of the mind. The accused has to prove that he had a total inability to control his conduct. The focus is on the accused’s lack of total volition rather than lack of consciousness as case law has mistakenly interpreted. Courts have mistakenly interpreted that there must have been a lack of consciousness due to a medical witness testifying that a person suffering from an automatic state will not be conscious at all times (see PP v Abdul Razak Dalek). Other courts have also interpreted that the accused may be aware of what they are doing and intend the consequences. How then does forensic psychiatry tie in with the insane automatism defence? Similar to unsoundness of mind defence under s 84(a) and (b), the court will refer to clinical evidence to assess whether the accused was legally insane at the commission of the alleged criminal act. The following examples demonstrate how psychiatric reports were used to mitigate the imposition of a higher sentence. Facts: The accused woke from sleep and brushed his teeth at the kitchen sink where he spied a knife next to the sink. He then stabbed his roommate, Pang, in the chest. Pang woke up with shock and ran out of the flat where he collapsed and died. Under s 304(a) of the Penal Code, Ch 224, the accused was charged for culpable homicide not amounting to murder which he pled guilty. Holding and reasoning: Granting a special judgement, the court reasoned that the accused was mentally unsound and would be a danger to society since he has no family to care for him. Moreover, the accused had a history of not complying with medical orders, which was not his first relapse. Dr Tommy Tan of the Department of Forensic Psychiatry at the Woodbridge Hospital (currently the Institute of Mental Health) assessed the accused. The accused had a history of mental illness dating back to 12 January 2001 when he was admitted to the hospital for setting fire to his landlord’s corridor. In his psychiatric report, Dr Tan stated that the accused was found to have psychomotor retardation and was depressed. The accused was unable to explain why he had killed the deceased and claimed that he was in a state between awake and asleep [at] the time of the alleged offence and “felt some force controlling him”. Dr Tan concluded that he could have had some paranoid beliefs about the deceased. Dr Tan stated that in his opinion, the accused had a ‘schizoaffective disorder’ at the time of the offence which ‘substantially impaired his mental responsibility for the acts that caused the death of the deceased’. When considering the sentence, since the accused had pleaded guilty, the court precluded him from claiming an acquittal under s 84. Hence, the court granted him special judgment to be imprisoned for life where he may seek medical treatment and special care. Facts: The accused shot a woman as she did not comply with his instructions to get out of her car. He also pointed a gun at a crowd when they approached him to diffuse the situation. He was charged under s 302 of the Penal Code. The accused brought a defence of automatism claiming he was suffering from a hypoglycemic attack. Holding and Reasoning: The court acknowledged that the accused was suffering from hypoglycemia which adversely affected brain functions. Whilst experiencing hypoglycemia, the sufferer can perform complicated tasks but have no recollection of what they did, as if they had been sleepwalking. A medical expert testified that it is impossible to be sure that the accused was suffering from a hypoglycemic attack, especially when no blood glucose measurements were taken when he was arrested. However, he likely had a convulsion based on his medical history, suggesting that he had episodic hypoglycaemic attacks. His wife also testified his hypoglycemia symptoms. However, the court held that while hypoglycemia was an internal cause of unsoundness of mind, the accused was sufficiently conscious of what he was doing when he fired the shot. Not all the deliberative functions of his mind were absent, and the accused was conscious; hence the defence of insane automatism could not be sustained. It is submitted that the court should have focused on the accused’s lack of volition and acknowledging hypoglycemia as an internal cause of unsoundness of mind. Based on the symptoms, the effect of the hypoglycemic attack is of disorientation rather than loss of consciousness. In some cases, the severity of symptoms may result in the sufferer losing control of his or her actions to support the claim in automatism. Hence, if the court emphasised a lack of volition, it is likely that the accused could be acquitted on the current s 84(c). The courts rely heavily on expert opinions to determine medical unsoundness of mind, giving rise to a finding of legal unsoundness of mind. As courts increase their focus on the role mental disorder plays in offending, more is expected from mental health services, especially those relating to forensic psychiatry. In a recent Court of Appeal case of Ong Pang Siew v Public Prosecutor, the court emphatically stated a need for a “prescribed clinical standard” for expert psychiatric evidence, and had no qualms about dismissing the forensic psychiatric opinions that fell short of the court’s own non-defined “clinical standard”. Not only is the volume increasing, but the expectations of forensic psychiatric assessments are rising with the courts signalling that they will judge the quality of forensic evidence as well. Therefore, forensic psychiatry is also essential in the legal system. At post-sentencing stages, various departments provide rehabilitation and treatment for mentally ill offenders. The Psychiatric Housing Unit (PHU), formed in 2011, includes intervention for offenders with mental disabilities and illnesses. The PHU oversees offenders suffering from mental disorders, which are clinical and manageable through psychological intervention and medications. Despite the utmost efforts by the prison staff and specialists, a small group of mentally ill offenders is deemed unsuitable for the mainstream prison regime. This group of mentally ill offenders are designated as Permanent Long Stayers, as their conditions are determined to be too severe to allow them to be discharged. The Prisons Clinical Psychology Unit works closely with the PHU, and provides psychological screening, overseeing individual psychological intervention. APCCA found the more prevailing diagnoses in mentally ill offenders to be schizophrenia (29%), substance abuse (22%), and depression (20%). Other common diagnoses include antisocial personality disorders and sleep disorders. Figure 2: Breakdown of Diagnoses in PHU There are various treatment plans and interventions in place to treat inmates with mental disorders. Psychologists and psychiatrists administer these from IMH and the Clinical Psychological Unit of the prison service. Psychological interventions focus on problems such as the propensity to pose a risk to others and self, or the experiencing of distress affecting daily functioning. A common therapy utilised is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), which focuses on changing unhelpful and negative thoughts and behaviours, and regulating emotions. CBT is commonly applied as a treatment for various mental disorders, ranging from depression to anxiety disorders. One of the PHU programme evaluation benchmarks is the number of disciplinary offences committed by offenders with mental disorders. A 67.5% reduction in their disciplinary offences between 2010 and 2012 positively validated the PHU system and framework. Aside from the prison service programmes, the Centre for Forensic Mental Health, under MSF, specialises in assessment and treatment for adolescents and adults with sexual and violent offending behaviours. Examples of these programmes include: In addition to in care interventions, the Institute of Mental Health (IMH) also provides aftercare services for offenders with chronic and severe psychiatric symptoms. One such aftercare programme is the Forensic Psychiatric Community Services, where each offender is assigned a social worker and a case manager to follow up on the offender’s case. Early engagement of these offenders in their pre-release phase and close follow up on their psychiatric treatment is crucial in minimising the propensity to relapse. The case of Ng Say Tiong is one example that highlights the importance of in care interventions, and aftercare services in helping mentally ill offenders better manage their conditions and minimising their propensity to relapse. Under his friends’ influence, Ng Say Tiong started taking heroin at the age of 18 and was sentenced to 3 years imprisonment. After his release, he continued to be involved in crimes and was jailed more than ten times, often on charges of drug offences and hurting others. His revolving door experience with jail and stress from caring for his brother, who suffered from developmental problems resulted in him abusing drugs as a form of escape. After a court referral to IMH, Say Tiong was convinced to commit suicide with his ward mate. Despite being saved by a nurse in his first suicide attempt, Say Tiong continue to attempt suicide in his 10-year prison sentence and was diagnosed with depression. He was provided with treatment and therapy for his depression in IMH and was released from prison in 2012. After his treatment, Say Tiong no longer leads a life of crime, and spends his time volunteering, with occasional visits to IMH from time to time to get medication for his depression. Say Tiong’s story is one of many, whose mental conditions are often a contributory factor to crimes’ commitment. With the proper mental health treatment, mentally ill offenders can better cope with their mental disorders and reintegrate back into society. The application of clinical psychology spans across various stages in the justice system, from pretrial to post-trial. In the pretrial and pre-sentencing stage, clinical psychology is essential in determining an accused’s fitness to stand trial and whether the accused warrants an MTO. In the trial stage, clinical psychology plays a contributory role in determining an accused’s criminal responsibility, especially when their mental states could have compelled them to commit those actions. In the post-trial stage, clinical psychology is essential in rehabilitating offenders, especially for those suffering from mental disorders, with specific treatment plans crafted as they serve their sentences. Although psychological interventions and treatments across these stages are mandatory for the accused, the potential to reduce their recidivism risk by targeting the roots of the problem and the various positive outcomes seen in offenders suffering from mental disorders prove the importance of applying clinical psychology in the forensic setting. Despite its importance, there have been instances when psychological and psychiatric opinions fell short of expectations, making them unsuitable to be used in court. Therefore, as proposed by the Singapore Psychological Society, a regulatory board for clinical forensic psychologists and psychiatrists is essential with the greater importance and emphasis on the standards of psychiatric opinions in Singapore’s justice system.Forensic Clinical Psychology in Singapore

Figure 1: Organization and practice of clinical forensic psychology in SingaporePretrial Assessments and Pre-sentencing Stage

Mental Disorder Defences in Court

Unsoundness of Mind

Insane Automatism

Case 1: Unsoundness of Mind

PP v Chia Moh Heng [2003] SGHC 108.

Case 2: Insane Automatism

PP v Kenneth Fook Mun Lee (No 2) [2003] MLJ

Post-sentencing and Rehabilitation

Conclusion

*The views and opinions expressed in this article do not constitute legal advice and solely belong to the author and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the NUS Criminal Justice Club or its affiliates.

Authors’ Bibliography

George Teo is a Year 3 FASS undergraduate and a member of the CJC-F “Forensic Psychology” project. He is pursuing a major in Psychology and a minor in Forensic Science. He has a strong interest in forensic psychology, specifically its applications to law enforcement and rehabilitative efforts.

Heidi Chiu is a Year 2 undergraduate from the Faculty of Law. As a member of the CJC-F “Forensic Psychology” project, she is interested in the applications of psychology and how forensics may impact the way the law is applied to accused persons in investigations.

Xin Hui is a Year 4 undergraduate student majoring in Psychology, with a minor in Forensic Science. As the project manager for Forensic Psychology in CJC-F, she is in charge of coordinating, advising and working together with her team to spread awareness of the use of forensic psychology in the legal setting. Intrigued by the marriage between her two academic backgrounds, she is interested in exploring the use of psychology in legal settings and seeks to champion its importance.